HETL Note: We are proud to present to our readers the first issue of International HETL Review 2104 and to open IHR Volume 4 with the academic article written by R. D. Willliams, Amy Lee, Alison Link, and David Ernst. The empirical study addresses an important aspect of the use of mobile technology in education – the significance of the sociocultural background in the processes around adoption and use of mobile technology in learning. The findings suggest that socioeconomic diversity needs to be considered when designing campus infrastructure and providing access to technology and choosing the pedagogical approach in order to create an engaging teaching and learning context. You may submit your own article on the topic or you may submit a “letter to the editor” of less than 500 words (see the Submissions page on this portal for submission requirements).

Author bios: Dr. Rhiannon D. Williams is a Research Associate in the Department of Postsecondary Teaching and Learning at the University of Minnesota. Her research examines first-year experience programming and how intentional engagement with diverse students in the classroom has the potential to support and further develop students understanding of themselves and each other as complex diverse individuals. Overall, her research grapples with the complexities, possibilities and limitations an equitable diversity discourse engenders in a higher education classroom. Contact email address: [email protected]

Author bios: Dr. Rhiannon D. Williams is a Research Associate in the Department of Postsecondary Teaching and Learning at the University of Minnesota. Her research examines first-year experience programming and how intentional engagement with diverse students in the classroom has the potential to support and further develop students understanding of themselves and each other as complex diverse individuals. Overall, her research grapples with the complexities, possibilities and limitations an equitable diversity discourse engenders in a higher education classroom. Contact email address: [email protected]

Dr. Amy Lee is in the Department of Postsecondary Teaching and Learning at the University of Minnesota. Her teaching and research focus on critical pedagogy, access/equity and intercultural development in higher education classrooms has produced three books and various articles including: Formative journeys of first-year college students (forthcoming, Higher Education Research and Development); Engaging Diversity in Undergraduate Classrooms (Josey-Bass, 2012); Engaging Diversity in First-Year College Classrooms (2012). Contact email address: [email protected]

Dr. Amy Lee is in the Department of Postsecondary Teaching and Learning at the University of Minnesota. Her teaching and research focus on critical pedagogy, access/equity and intercultural development in higher education classrooms has produced three books and various articles including: Formative journeys of first-year college students (forthcoming, Higher Education Research and Development); Engaging Diversity in Undergraduate Classrooms (Josey-Bass, 2012); Engaging Diversity in First-Year College Classrooms (2012). Contact email address: [email protected]

Alison Link holds a Bachelor’s degree in international relations from Grinnell College and a Master’s degree in multicultural college teaching and learning from the University of Minnesota. After her undergraduate degree, she participated in the Austrian Fulbright Commission’s English Teaching Assistantship program, where she grew interested in the intersections between technology and global education. She currently works as an academic technologist for the University of Minnesota Extension. Contact email address: [email protected]

Alison Link holds a Bachelor’s degree in international relations from Grinnell College and a Master’s degree in multicultural college teaching and learning from the University of Minnesota. After her undergraduate degree, she participated in the Austrian Fulbright Commission’s English Teaching Assistantship program, where she grew interested in the intersections between technology and global education. She currently works as an academic technologist for the University of Minnesota Extension. Contact email address: [email protected]

Dr. David Ernst is the Chief Information Officer in the College of Education and Human Development at the University of Minnesota. He brings his extensive background in education to his role, including 14 years of teaching and a PhD in Learning Technologies. His passion lies in developing innovations that help faculty teach and students learn. Contact email address: [email protected]

Dr. David Ernst is the Chief Information Officer in the College of Education and Human Development at the University of Minnesota. He brings his extensive background in education to his role, including 14 years of teaching and a PhD in Learning Technologies. His passion lies in developing innovations that help faculty teach and students learn. Contact email address: [email protected]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Minding the Gaps: Mobile Technologies and Student Perceptions of Technology

Rhiannon D. Williams, Amy Lee, Alison Link, & David Ernst

University of Minnesota, U. S. A

Abstract

Mobile devices are becoming increasingly ubiquitous within higher education, but our understanding of how different economic populations of students are responding to this reality is still limited. This study looks at survey data from a large-scale undergraduate tablet initiative at a large Midwestern research institution in the College of Education and Human Development. The data were collected from a group of 351 students who participated in a first-year experience program, and who received iPads for academic and personal use during their enrollment in the college. One hundred and twenty-seven students from the sample were enrolled in a federally funded program that supports students who are from low-income families and are either first-generation college students or students with disabilities. The survey data were disaggregated by student status with respect to the program and analyzed to understand more about how these groups engaged with the iPad as part of their first-year college experience. As institutions continue integrating mobile devices into higher education settings, this study suggests we should have heightened awareness of how these devices may be perceived and utilized by different populations of students.

Keywords: First year students, iPads, technology identity, student engagement, diversity

Introduction

In the last decade, increasingly affordable mobile devices, wide wireless network availability, and the growth in the number of services delivered to mobile platforms has led to an unprecedented rate of adoption of mobile devices (DeGusta, 2012; Pinson, 2012). On the whole, the expansion of mobile technologies means that concerns related to material access to networked technologies–concerns that have been prominent in “digital divide” discussions in the last decades–are changing and will continue changing even more profoundly in the coming years. Given this fast development, our understanding of the experience of students from different socioeconomic groups’ experiences with educational technologies, particularly mobile technologies is still in the nascent stages.

This study examined how students who received iPads as they entered college reported on their attitudes, usage, and beliefs related to mobile technology and its use in their first year curriculum. This study examines survey data from a large-scale undergraduate tablet initiative at a large Midwestern research institution in the College of Education and Human Development. In particular, we consider whether and to what extent there is a “digital divide” evident in this population and explores possible implications for mobile learning technology for use in first-year learning environments. The 351 first-year students who were asked to participate in the study represented a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds, from families who income levels are at or below U.S. defined poverty level to families whose income is in the top 1%. The main questions that inform this particular study are:

- How did first-year students in the study respond to questions on their technology identity, their iPad usage, and the relationship between the iPad and their educational experience?

- Do different patterns of responses emerge across socioeconomic groups?

While the results of this study provide more questions than they answer, the data invite subsequent research that can inform practitioners’ capacity to critically reflect on and explore the integration of mobile technology in higher education classrooms.

Mobile Devices in Higher Educational Contexts

Mobile technologies are ushering in changes in the traditional “digital divide” discourse. Students today can benefit from a much more diverse, embedded, and affordable array of technologies than ever before. Scholars have noted the potential for mobile devices (versus traditional laptops) to facilitate ‘ubiquitous’ learning–learning that becomes embedded in everyday life (Murphy, 2011; Peng, Su, Chou, & Tsai, 2009; Sharples, 2000; Sharples & Rochelle, 2010). Mobile devices have the potential to facilitate integrative and collaborative learning, promoting interpersonal communication in educational settings, encouraging students to positively express their individuality and build student-to-student, and student-to-educator relationships (Wankel & Blessinger, 2013). In addition, they have increasingly powerful media production capabilities: most can capture still images, and many have high-definition video and sound recording capabilities.

The capabilities of and potential for mobile devices to be integrated into a higher education classroom are just starting to be explored and documented. For example, a biology class at McGill University used tablets to enhance experiential learning such as gathering rich data in the field and engaging in real-time interaction with their instructor and the larger research community (Finkelstein, Winer, Buddle, & Ernst, 2013). To date, however, the higher education literature contains only a few examples of how tablet devices have been integrated into students learning environments—both in the physical classroom and outside and used to engage students, their local environments and the scholarly community.

Changing Conceptions of the Digital Divide

Over the past two decades, mobile devices especially have significantly impacted who has access to the Internet and the resources to develop as a competent technology user. No longer is it the case that only well-resourced schools or youth who come from more economically and educationally advantages educated families have access to Internet-connected devices. For example, according to a report by the National Center for Education Statistics, in 1995 only 8% of all computers in schools had Internet access; by 2005, 97% of school computers were wired for Internet (Snyder & Dillow, 2011, p. 173). A 2013 Pew Report found that teens who came from lower-income and lower-education households were somewhat less likely to use the Internet in general (mobile or wired), but that they were in many cases just as likely as their higher-income, more highly educated peers to use their cell phones as a primary point of access (Madden, Lenhart, Duggan, Cortesi, & Gasser, 2013). In other words, current data no longer support the assumption that youth from households that are characterized by low-income or lower-educational attainment levels are less exposed to, experienced in, and savvy with various technologies. As one scholar notes, there is a current need to “explode the essentialist constructions of minority youth as low-tech, IT outsiders” (Everett, 2008, p. 4).

The “digital divide” has traditionally referred to disparities in terms of material access to technology. In particular, the focus has been on whether low-income students have sufficient physical access to hardware, software, and Internet services to perform the computing tasks that are expected of them in their coursework and required for a twenty-first century citizen. In a review of the last five years of digital divide research, however, Van Dijk found that the focus has widened from a primary emphasis on “material” concerns about access to devices and infrastructure to one that includes increasing attention to “social” concerns that consider students’ motivational, psychological, or cultural backgrounds (2006, p. 223). Van Dijk summarizes this shift by stating that, “technology access should be seen as a process with many social, mental, and technological causes and not as a single event of obtaining a particular technology” (2006, p. 224).

As we take stock of the quickly changing landscape of increased access to technology, it is also important to consider components beyond mere physical access to devices: students’ “technology identities” and sense of self-efficacy as a technology user in terms of their confidence and attitudes towards using various technologies is an important consideration for educators. It is reasonable to hypothesize that a student’s technology identity will influence that individual’s engagement with mobile technology in educational settings. Goode (2010), for example asserts that “beyond skills, students’ varied computing histories can result in a range of technology identities that impact their relationship with technology in their academic, social, and career aspirations” (p. 583). More research is needed that investigates the relationship between students’ attitudes towards and confidence about technology, their technology identity, and their technology usage.

iPad Initiative in a First Year Experience Program

This study reports on data collected in the pilot phase of a college tablet initiative with first year students and faculty who teach them. This initiative took place at the University of Minnesota, a public, land-grant research university with approximately 30,000 undergraduates and twelve undergraduate colleges located in the Twin Cities, a large, mid western metropolitan area. In fall 2010, the College of Education and Human Development (CEHD) at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campus and the Department of Postsecondary Teaching and Learning (PsTL) launched a mobile learning pilot which involved the use of iPad tablets in courses in the First Year Experience (FYE) program. A majority of first year students in CEHD enroll in FYE which has fall and spring course components. Approximately 425 students matriculate into CEHD annually.

The iPad project has taken place over four years and the pilot phase took place in 2010-2011 and 2011-2012. In the initial pilot phase, no strategic pedagogical intervention was being developed or tested. This pilot stage was developmental with the purpose of providing access to all faculty and students in the FYE program and to collect data about the impact of that access on their use of and perceptions about learning technologies. Twenty-seven instructors in CEHD’s First Year Experience (FYE) program participated that year by incorporating the iPad in their course design, assignments, and daily classroom instruction. In each year of the project, incoming FYE students have received iPads at orientation, with no cost to the student because the pilot iPad project was funded by private donation. Academic technology staff provided faculty with technical training on the iPads and online tutorials were made widely available. Students were allowed to keep their iPads as long as they were enrolled in CEHD. In addition, they were able to use personal Apple accounts to download apps, manage their devices, and use the iPads as they saw fit for personal and course-related activities.

The initial focus of the pilot iPad project was quite broad, given that iPads were one of the first mainstream tablet devices available on the market and little research existed on how tablets could effectively be used to promote learning in higher education classrooms. The college’s stated goal for the pilot was to expand access to those students who may not otherwise be able to afford the learning technologies that the device supports. A secondary goal of the pilot was to investigate whether instructors might utilize open source course materials to a level that would enable future students to purchase tablets without an increase in their overall expenses (as the cost of the tablet would be made up for by decrease in textbook costs).

Because of the experimental nature of the project, instructors and students had substantial autonomy as they explored the device’s potential within their specific learning environments. Instructors had access to technical training and support through the College’s Academic Technology Services, both via group workshops and one-on-one consultation with technology support staff. Instructors also received periodic communications from technology staff about basic technical functions of the iPad and different apps or features. It was at the discretion of each instructor to consider how the iPads could support their curricular goals and to what extent to integrate iPad-supported activities into their pedagogy. As a result, students’ experience varied somewhat based on the course and their instructors’ decisions about how to integrate or utilize the iPads. Some instructors focused more on the individual and routine usage capabilities, such as reading and annotating PDFs, accessing Power Points on Moodle (the university’s leaning management system), or taking quizzes. Other instructors focused on the device’s media creation capabilities, creating “digital stories” or field-based projects involving data collection and analysis. Consequently, the early phases of assessment were also relatively broad, with the aim of capturing how instructors and students were using iPads in and out of the classroom for teaching and learning.

Survey Methods

In year two (2011-2012) of the iPad initiative, several assessment methods were utilized to collect data about FYE (TRiO and Non-TRiO) students’ learning experiences with the iPad. The main assessment method used for this study was a survey. This survey was distributed to all students enrolled in a learning community in the spring of 2012.

Survey Population

Over a two week period in April, 2012, faculty in the First Year Experience (FYE) program asked students to complete the iPad survey on their iPad or laptop in class. In total, 351 students were enrolled in FYE that semester; 274 students (78%) completed the survey. Of the respondents, 94 were enrolled in the “TRiO Student Support” program which is a federally funded program to support access to and success in higher education for historically underserved student populations. TRiO Student Support was established in 1976 by the U.S. Department of Education and the programs are housed in colleges across the U.S.A.

Our institution does not provide access to disaggregated data by income and so we used the TRiO designation as a proxy in analyzing our data (See Table 1). Currently, the U.S. Department of Education requires that TRiO students come from families that meet the federally established low-income requirements, for a family of 5 this is $41,355. However, the median family income for 2012 incoming TRiO students in CEHD was $27,000 (family of 5) which is defined as poverty-level by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. While proxy is likely not inclusive of all low-income students in our population, it is certain that all students coded as TRiO are low-income. As noted in Table 1 our survey population was proportionately representative of the broader CEHD first year student cohort.

Table 1. Survey population- TRiO/ Non-TRiO

| Spring 2012 Survey | Total | Non-TRiO | TRiO |

| Total # of first-year students | 433 | 282 | 151 |

| Students enrolled in learning communities | 351 | 224 | 127 |

| Students who took the survey | 280 | ||

| Complete responses included in analysis | 274 | 180 | 94 |

| Response rate (based on complete responses) | 78% | 80% | 74% |

Survey Instrument and Design

The main assessment instrument developed by the iPad team was a survey focused on participating students’ perceptions, usage, and educational experiences with respect to the iPad and their learning. First, students were asked to self-report on devices they either owned or had regular access to in their home. This set of questions was designed to provide an understanding of the devices students had previous access to and experience using. The rest of the survey was organized around three constructs: 1) Technology identity; 2) Course-related iPad use and personal iPad use; and 3) Educational experience with the iPad. Some of the survey questions in these constructs were informed by the 2011 ECAR National Study of Undergraduate and Information Technology survey (ECAR, 2011). The iPad pilot team developed the rest of the questions regarding the course-related iPad use and personal iPad, as the ECAR study did not contain questions specific enough to capture nuanced details of students’ iPad use. In addition to the scaled response questions, students were asked three open-ended questions: 1) Please describe how you use your iPad on a typical day; 2) Please describe the best way that the iPad was used in connection with one of your classes; 3) If you could tell your instructors anything about your experience using the iPad for course-related activities, what would you tell them?

Technology identity

The technology identity items asked students to self-report on elements related to their self-efficacy as technology users. A principal component analysis showed that the individual survey items broke down into two scales, which the research team labeled as students’ perceptions of their confidence about technology, and students’ self-reported enthusiasm for using technology. Items in the two scales of the Technology Identity construct were on a four-point scale. Response options included: 1= Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Agree, 4=Strongly Agree. The first scale (students’ personal and peer perceptions of technology confidence) had three items and the second scale (students’ self-reported enthusiasm in using technology) had nine items. The two scales have high levels of reliability, as measured by the Cronbach’s alpha statistic (Table 2).

Course-related iPad use and personal iPad use

The course related and personal iPad usage items asked students to self-report the ways they used their iPad on a regular basis. The inclusion and wording of these items was informed by the assessment team’s pilot year experience working with students and faculty. Items in this construct were on a six-point scale. Response options included: 0=Never, 1= less than once a week, 2= once a week, 3=several times a week, 4=once per day, and 5=several times a day. Once the data was cleaned and preliminary analysis began, we realized that in terms of understanding students’ iPad use in the classroom, several items on the scale could be collapsed. Therefore, the new scale included a four-point scale: 0=Never, 1=less than once a week, 2= at least once a week, 3= at least once a day. The construct had a high level of reliability, as measured by the Cronbach’s Alpha statistic (Table 2).

Educational Experience with iPad

The educational experience items asked students a series of questions about iPad use and their perceptions as to how and whether it enhanced their learning experience. Items in this construct were on a four-point scale. Response options included: 0=Strongly Disagree, 1= Disagree, 2=Agree, and 3= Strongly Agree. Again, this construct had a high level of reliability, as measured by the Cronbach’s Alpha statistic (Table 2).

Table 2. Construct statistics

| N=274 | Technology Identity | iPad Usage | Educational Experience | |

| Enthusiasm | Confidence | |||

| Valid | 253 | 259 | 247 | 253 |

| Missing | 21 | 15 | 27 | 21 |

| Mean | 22.89 | 9.76 | 18.08 | 44.53 |

| S.D. | 4.451 | 1.86 | 10.583 | 11.316 |

| Cronbach’s α | .82 | .87 | .924 | .957 |

Data Analysis

Data analysis of the survey results comprised three stages. First, we downloaded the survey responses from our college’s server and initially identified 280 responses. After we cleaned the data by identifying duplicates, incomplete responses, and incorrect student ID numbers, we had 274 freshman respondents whom gave permission for us to match their responses to a variety of demographics (i. e., race, gender, and program).

Preliminary data analysis revealed normal distributions of responses on the technology enthusiasm and the course-related/personal iPad usage scales. The educational experience and technology confidence scales were slightly skewed to the right, with responses tending slightly towards the “agree” and “strongly agree” end of the reporting scale. Next, we ran cross-tabulations and frequencies between the two groups of students (TRiO and Non-TRiO) and the items within each of three constructs. The result of this step enabled us to better understand our primary research question (“how did first-year students respond to questions on their technology identity and their iPad usage?”) and to consider the relationship between this data and their educational experience.

Cross-tabulation and frequency analysis led us to note differences in responses between TRiO and Non-TRiO students across all three constructs. In order to develop a nuanced understanding of responses related to our secondary research question (“do different patterns of responses emerge across socioeconomic groups?”), we needed to run Chi-square and Cramer’s V statistics. These statistical analyses helped provide a detailed understanding of individual construct items that differed, by significance and magnitude, respectively, between the two socioeconomic groups (TRiO and Non-TRiO).

Combining the results from the frequency, Chi-Square and Cramer’s V statistical analyses helps us develop a greater understanding of how TRiO and Non-TRiO students report using their iPads, think about the iPad in relationship to their tech ability, previous access to technology and their first-year educational experience. This combination of analysis helps us to understand the basic differences in frequency of response, the difference in pattern of responses, and the significance and magnitude of any differences of responses these two groups may have on items within each survey construct. The items where there are significant differences or no differences (where differences may have been expected), in particular, challenge us to think about the implications for broader institutional policies, classroom practice, and engagement in an academic learning environment for different groups of students.

Findings

The analyzed data revealed some interesting differences and similarities between the TRiO and non-TRiO students in the areas of technology access, technology identity, use in class, and perceptions of education experience.

Technology Access

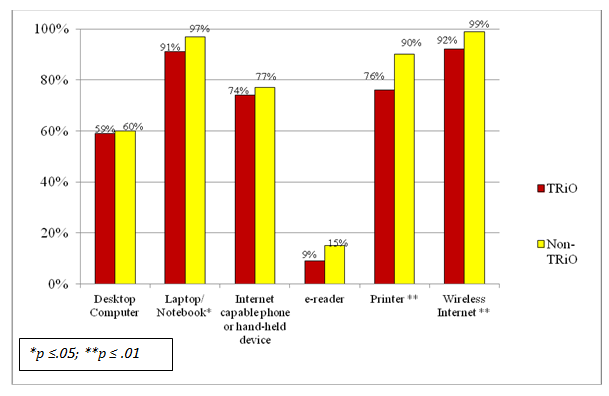

The first set of questions on the survey asked students about their access and previous exposure to different devices. Our findings revealed that, with the exception of two items, TRiO students reported the same levels of personal access to technological devices compared with Non-TRiO students (Figure 1). For example, 59% of TRiO students and 60% of Non-TRiO students reported access to desktop computers, which represented no significant difference between the two groups for desktop computing access. TRiO students reported slightly lower access to an Internet-capable phone or handheld device: 74% in comparison to 77% reported by non-TRiO students. Significant differences were noted on two items: access to a printer (76% of TRiO students reported access, and 90% of non-TRiO) and wireless Internet at home (92% for TRiO students compared to 99% for non-TRiO students.

Figure 1. Technology access

Regarding prior exposure to classroom mobile devices before coming to college, 30% of students reported previous use of mobile devices for school activities. This was low overall, but showed no significant difference across TRiO and non-TRiO students. Overall, our findings in the area of material access were in line with the Pew research (2012) cited in the “digital divide” discussion above. One would expect that students’ access to mobile devices and smartphones will continue to increase as these devices continually decrease in price (Madden et al., 2013; Nielson Report, 2010).

Technology Identity

When it comes to adopting new mobile technologies such as iPads, it seems likely that students may have varying levels of confidence and enthusiasm and that these factors will affect how they respond to mobile learning experiences. These data provide a snapshot of the current technology skills and attitudes of entering college students.

Survey results show that TRiO students in the study did not differ significantly from their non-TRiO peers when it came to questions of personal confidence surrounding technology (Table 3). A majority of all students surveyed reported high levels of confidence in their ability to use technology and iPads effectively in their coursework and personal lives. TRiO students were even slightly more likely than their non-TRiO peers to report being confident in their ability to use technology in their courses. For example, 42% of TRiO vs. 32 % of Non-TRiO students strongly agreed that they were confident in their ability to use technology as needed in their courses.

Table 3. Technology confidence

| df | Χ2 | Cramer’s V | |

| I am confident in my ability to use technology as needed in my courses | 3 | 8.61 | 0.182* |

| I am confident in my ability to use my iPad effectively in my personal life | 3 | 3.74 | 0.120 |

| I am confident in my ability to use my iPad effectively for my coursework | 3 | 4.31 | 0.129 |

| p<.05 |

TRiO students did, however, differ in interesting ways from their non-TRiO peers when it came to questions of enthusiasm (Appendix 1). TRiO students reported being more engaged and enthusiastic about technology on a number of items. For example, TRiO students were significantly more likely to report that they enjoyed reading about advances in consumer electronics and digital devices (χ2=26.84, p<.001, V=.32), that they frequently looked for new software or apps (χ2=16.99, p<.001, V=.26), and that they often told friends about technology products of interest to them (χ2=14.36, p<.01, V=.24). Forty-nine percent of TRiO students vs. 20% of non-TRiO students agreed or strongly agreed that they liked to read about advances in consumer electronics and digital devices (Appendix 1).

Using iPads in Class

In terms of course-related purposes, TRiO students reported using their iPads more frequently than non-TRiO peers on almost every item. We note that, for every course-related usage, TRiO students’ responses were significantly different from their non-TRiO peers. For example, TRiO students were significantly more likely to look up course-related information with their iPad than their Non-TRiO peers (χ2=29.34, p<.001, V=.335) (Appendix 2). Seventy-one percent of TRiO students vs. 61% of Non-TRiO students would look up information for courses at least once a day.

Using iPads for Everyday Needs

Regardless of student group, students’ most frequent course-related iPad use was for what we refer to as “routine” use. Routine use includes common, day-to-day tasks that enable students to acquire or connect with course-related materials. These tasks include checking the course Moodle site, annotating articles, or finding relevant information or resources online. Fifty-three percent of TRiO students reported using their iPads daily to look up information compared to 27% of Non-TRiO students. Interestingly, for the most routine needs, the pattern of responses for TRiO and Non-TRiO students were mirror opposites.

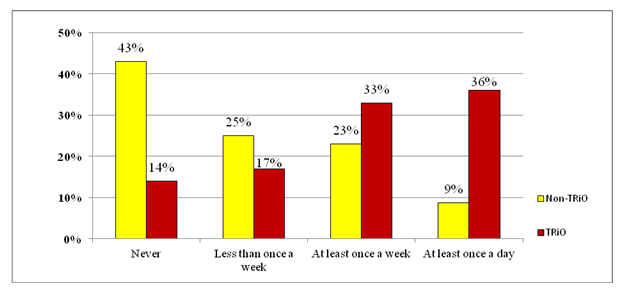

One example is given in Figure 2. Only 14% of TRiO students said that they never annotated or took notes with their iPad compared to 43% of their non-TRiO peers reporting that they never annotated or took notes with their iPad. On the other end of the spectrum, 36% of TRiO students responded that they annotated or took notes at least once a day compared to 9% of non-TRiO students.

Figure 2. Annotating and taking notes

Using iPads to Collaborate/Connect

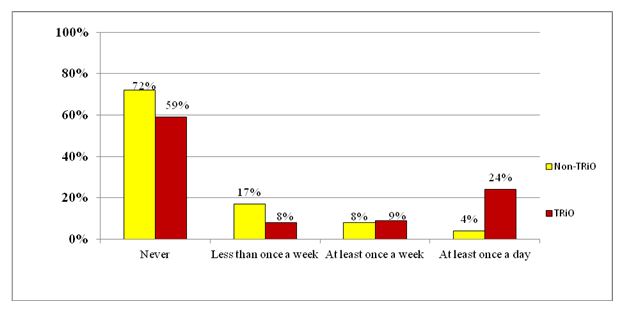

While not as frequent as routine uses referred to above, students did report using their iPads to connect with peers whether through Skype or Facetime and view multimedia such as You Tube, or listen to podcasts. Again, there were differences in how the two groups responded, though the pattern is different, with TRiO and non-TRiO students’ responses more “parallel”. For example, 24% of TRiO students stated they used their iPads to video or text chat at least once a day compared to 4% of non-TRiO students. On the other end of the response scale, 72% of non-TRiO students noted that they never used Skype or Facetime for course-related activities, compared to 59% of TRiO students (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Video or text chat

Using iPads to Generate/Create

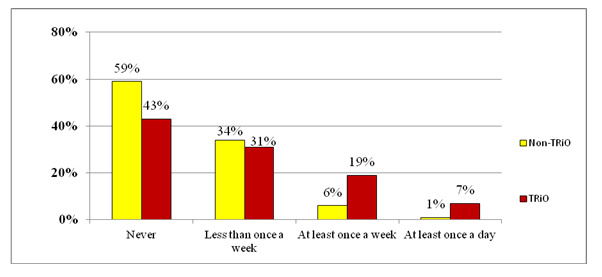

The last category of the usage scale was using the iPad as a multimedia creation tool. While some students reported having recorded music, taken photos, or created a digital story, these activities were much less frequent than the routine uses described above. This was in part due to different course requirements: for example, some FYE courses required students to create a digital story, while other courses did not incorporate any particular multimedia creation activities. Fifty-nine percent of non-TRiO students said they never recorded or edited videos with their iPad, compared to 43% of TRiO students (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Video recording or editing

Educational Experience

Overall, students responded positively on the educational experience scale. Many reported that using the iPad enhanced their learning experience in the classroom. TRiO students responded with more intensity on all items in this construct (Appendix 3). For example, 40.4% of non-TRiO agreed that iPads helped them develop confidence in understanding course material, and only 11% strongly agreed. On this same item, 42% of TRiO students agreed and 30% strongly agreed. Overall the TRiO and non-TRiO group means showed significant differences, with the TRiO group having an average mean of 3.08 and non-TRiO group an average mean of 2.67.

There were two items on the educational experience scale in which TRiO and non-TRiO students responded fairly similarly: having an iPad helped them learn about multimedia (audio, video, animation) and nurtured a variety of learning styles (visual, auditory, kinesthetic).

When we looked at the items with the highest means (i. e., where responses tended most strongly towards “agree” and “strongly agree”), they were roughly the same across TRiO and non-TRiO students. The aspects of their educational experience that students most frequently reported as enhanced by their use of iPads were: 1) made doing course activities more convenient (77% of non-TRiO students agreed or strongly agreed and 93% of TRiO students agreed or strongly agreed); 2) facilitated multiple types of learning activities (75% of non-TRiO students agreed or strongly agreed and 92% of TRiO students agreed or strongly agreed); and 3) helped me to learn about multimedia (71% of non-TRiO students agreed or strongly agreed and 74% of TRiO students agreed or strongly agreed).

Discussion

The research set out to answer the questions:

- How did first-year students in the study respond to questions on their technology identity, their iPad usage, and the relationship between the iPad and their educational experience?

- Do different patterns of responses emerge across socioeconomic groups?

Our study addressed differences between TRiO Students and their non-TRiO peers with respect to technology identity, usage and relationship between the iPad and their educational experience. From our findings we understand that TRiO students had access to and are using mobile technologies in different aspects of their academic lives. While TRiO students may not have had the same level/ amount of access to mobile technologies prior to college, the way they identified themselves in relation to technology, the ways in which they interacted through the iPad with peers and instructors, and the ways in which they viewed their education experience were at least on par with and frequently significantly stronger than the non-TRiO students in our study. We will discuss the possible implications for mobile learning technology in our conclusion.

Technology Identity

The traditional digital divide assumes that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds have less access to and are less comfortable with technologies. Yet, our findings suggest that TRiO students had almost equal access to mobile technologies as their Non-TRiO peers. In addition, when looking at a set of questions around one’s technology identity, students from less privileged socioeconomic groups had an equivalent or stronger technology identity than their peers. For example, in the technology identity section of the survey, students were asked if “My friends think of me as a knowledgeable source of information for technology”. If one used a traditional ‘digital divide’ lens, they would hypothesize that TRiO students because of their socioeconomic background would be less comfortable with technologies, as such TRiO students would agree or strongly agree less frequently than Non-TRiO students. However, when we ran frequencies for each group we found that 54.8% of Non-TRiO students strongly agreed or agreed and 67.3% of TRiO students strongly agreed or agreed with this statement. This has potential implications for how TRiO and Non-TriO students perceive and think about technology as a learning tool. As Goode (2010) explains students who “have robust beliefs about their technological proficiencies, believe that technology is important, are eager to learn more about technology, and sense there are opportunities to learn more about computing” (p. 590).

Social Impact Across Socioeconomic Groups

Our findings suggest that the iPads facilitated more interaction with peers and instructors for TRiO students than for Non-TRiO students. This kind of “connectedness” is essential to students transitioning to college and is evidence that technologies should be considered as part of the equation when designing structures to support student engagement and sense of belonging during the transition to college. It also suggests a conceptual shift may be in order from thinking about technologies as mere tools to the idea that they play a social role for students entering college. This means that educators need to have a complex, ever-evolving relationship with the technologies we use to support students within and outside of class. Administrators and educators need to be mindful of technologies’ social role when improving campus technology infrastructure. Social benefits and also potential consequences need to be considered when designing everything from computer labs, to short-term equipment check-out systems, to large-scale lending programs such as the CEHD iPad initiative.

Student Engagement

Student engagement as defined by Kuh (2008) consists of the amount and quality of time spent on educationally purposeful activities. Engaging students in educationally purposeful activities can benefit all students, but research indicates that those benefits are even greater for students who are from historically underserved populations (Kuh, Cruce, Shoup & Kinzie, 2008, p. 555). We found this to be true in this mobile initiative. The data shows that the perceived benefits by students were significantly higher for TRiO students. Further research will help educators understand the link between how purposeful technology use both inside and outside of the classroom may continue to benefit students. It will also be important to explore whether certain subsets of students—similar to the TRiO students examined in this study—may even enjoy stronger benefits from the purposeful use of technologies for learning.

In addition, one of the main components of student engagement is motivation. In learning theory, motivation is described as the personal willingness to engage in a learning activity. Learning tends to be more effective when students are motivated to construct knowledge in ways that are meaningful to them, and instructors play a vital role in fostering and facilitating this knowledge development (Lee & Hoadley, 2007; Morse, Littleton, Macleod, & Ewins, 2009). Educators will want to continue exploring the different uses for mobile technologies outlined in this study, from “routine” uses to “collaborating” uses to “generating/creating” uses. Different uses will stimulate students’ willingness and enthusiasm in different ways, and educators can embrace this variety to explore what best stimulates students’ motivation across different learning contexts and socioeconomic groups.

Conclusion

Our study has reported on use and perceptions of technology in an initiative in which access to was the priority for phase 1. As noted earlier, this phase did not require or suggest pedagogical interventions and the expectation was that those would emerge once faculty had the opportunity to experiment with and use the devices. Our current study provides information on how subpopulations within our cohort reported interfacing and interacting with these technologies and a baseline and suggests particular areas for subsequent research. A limitation of the study, and an area for future research, is information about how or to what extent the various first-year instructors integrated iPads into each course’s curriculum and pedagogy. This information would be important in developing an understanding of the relationships between student usage and instructor intentionality. It would be useful to understand what other devices students brought or had access to for course-related activities. All students (not only TRiO students) in the program received an iPad from the college so that was a consistent factor in our study. It is impossible to speculate as to the impact of a free device on students’ (whether TRiO or non-TRiO) attitudes about using learning technologies. Our results led us to want to investigate this further. Finally, when students reported on their access to technology, they were not asked to include information about how many individuals shared the computer or mobile device and/or whether they had “anytime” access to it. Therefore, we cannot form conclusions or test hypotheses about the relationship between students’ attitude towards their iPad and their ‘anytime’ access to other technology devices.

Research suggests that college students who are first-generation, and/or low-income are more likely to commute and to work off-campus. Does having an iPad provide opportunities to expand the traditional borders and boundaries of the classroom for such students? There is an opportunity to investigate whether or not there is a correlation between learning styles and a particular device; for example, does a tablet offer specific functionality that benefits some students more than others?

Mobile technologies are ushering in changes in the traditional “digital divide” discourse: students today can benefit from a much more diverse, embedded, and affordable array of technologies than ever before. Research on pedagogical interventions involving mobile technologies in higher education contexts that positively impact student learning and engagement is still in an emergent stage in the literature. There is, however, a growing body of literature investigating the interdependence of technology, pedagogy, and content knowledge (see, for example, TPAK.org). Wankel and Blessinger’s (2013) series of edited volumes on mobile technologies and student engagement titled Increasing Student Engagement and Retention using Technologies in Higher Education focuses on how instructors used mobile technologies in order to facilitate student engagement. As the editors note in the series introduction, “if the course is designed based on sound pedagogical principles and grounded in appropriate learning theories and sound content knowledge, the mediated discourse technologies [for example, mobile technologies,] have the potential to provide a more effective way to encourage student participation and foster a more meaningful sense of belonging and community” (Wankel & Blessinger, 2013, p. 8). More research is needed that explores the impact of and establishes models for incorporating mobile devices in ways that are intentionally integrated within the context of course learning goals and environment.

This study sought to stimulate a conversation about the intersections between mobile technologies, access, and student engagement across diverse higher educational contexts. TRiO students in our population reported behaviors or attitudes associated with high-impact practices when reporting on their engagement of mobile technologies in the classroom. Therefore our study results suggest that when thinking about and addressing student engagement, access, and success we would be wise to include in the discussion mobile technologies use across all socio-economic groups.

References

DeGusta, M. (2012). Are smart phones spreading faster than any technology in human history? Retieved from http://www.technologyreview.com/news/427787/are-smart-phones-spreading-faster-than-any-technology-in-human-history/.

Educause Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) (2011). ECAR National Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology. Retrieved from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERS1103/ESI11D.pdf

Everett, A. (Ed.). (2008). Learning Race and Ethnicity: Youth and Digital Media. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Finkelstein, A. B. A., Winer, L. R., Buddle, C. & Ernst, C. (2013). Tablets in the Forest: Mobile Technology for Inquiry-Based Learning. Educase Review Online. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/tablets-forest-mobile-technology-inquiry-based-learning.

Goode, J. (2010). Mind the gap: The digital dimension of college access. The Journal of Higher Education 81(5), 583-618.

Kuh, G. (2008). High-Impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Kuh, G.D., Cruce, T. M, Shoup, R., Kinzie, J., & Gonyea, R. M. (2008). Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first-year college grades and persistence. Journal of Higher Education, 79(5), 540-563.

Lee, J. J., & Hoadley, C. (2007). Leveraging identity to make learning fun: Possible selves and experiential learning in massively multiplayer online games (MMOGs). Innovate Journal of Online Education, 3(6). Retrieved from http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=348

Morse, S., Littleton, F., MacLeod, H. & Ewins, R. (2009). The theatre of performance ppraisal: Potential for role play training in second life. In (Eds.) C. Wankel and J. Kingsley, igher Education in Virtual Worlds: Teaching and Learning in Second Life, Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Madden, M., Lenhart, A., Duggan, M., Cortesi, S., & Gasser, U. (2013). Teens and technology 2013. Pew Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Teens-and-Tech.aspx

Murphy, G. (2011). Post-PC devices: A summary of early iPad technology adoption in tertiary environments. e-journal of Business Education & Scholarship of Teaching, 5(1), 18-32.

Nielson Report (2010). U. S. teen mobile report calling yesterday, texting today, using apps tomorrow. Retrieved from http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/newswire/2010/u-s-teen-mobile-report-calling-yesterday-texting-today-using-apps-tomorrow.html

Peng, H., Su, Y., Chou. C., & Tsai, C. (2009). Ubiquitous knowledge construction: Mobile learning re-defined and a conceptual framework. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(2), 171–183.

Pinson, J. (2012). The internet’s growing mobile faster than you thought. Retrieved from http://www.messagesystems.com/blog/?p=848.

Sharples, M. (2000). The design of mobile technologies for lifelong learning. Computers & Education, 34, 177-193.

Sharples, M. & Roschelle, J. (2010). Guest Editorial: Special issue on mobile and ubiquitous technologies for learning. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 3(1), 4-5.

Snyder, T. D., & Dillow, S. A. (2011). Digest of Education Statistics 20110, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2011015

Wankel, C. & Blessinger, P. (2013). Increasing student engagement and retention using online learning activities: Classroom response systems and mediated discourse technologies. Cutting-Edge Technologies in Higher Education Series, Vol. 6, Emerald Publishing.

Van Dijk, J. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics, 34, 221-235.

Appendixes

Appendix 1. Technology enthusiasm

| df | χ2 | Cramer’s V | |

| My friends would describe me as “into” the latest technology | 3 | 3.175 | 0.111 |

| My friends think of me as a knowledgeable source of information for technology | 3 | 6.314 | .156 |

| I am enthusiastic about consumer electronics and digital devices | 3 | 10.74 | 0.203** |

| I am excited about the Internet | 3 | 6.92 | 0.164 |

| I like to read about advances in consumer electronics and digital devices | 3 | 26.84 | 0.322*** |

| For me, technology is frustrating | 3 | 3.369 | .119 |

| I think trying to keep up with the changes in technology is a hassle | 3 | 2.370 | .095 |

| I frequently look for new software or apps | 3 | 16.99 | 0.256*** |

| I often tell friends about technology products that interest me | 3 | 14.36 | 0.235** |

| *p ≤.05; **p ≤ .01; ***p ≤ .001 |

Appendix 2. Ways students reported on course-related iPad use

| df | χ2 | Cramers V | ||||

| Routine Course-related UseAccess Moodle with my iPad | 3 | 13.87 | 0.231** | |||

| Looking up information online with my iPad | 3 | 29.34 | 0.335*** | |||

| Reading articles and texts online with my iPad (news sources, blogs, websites, and periodicals) | 3 | 18.25 | 0.264*** | |||

| Writing brief notes or messages on my iPad (such as e-mails, class notes, or reminders) | 3 | 8.59 | 0.182 | |||

| Using my iPad to annotate and take notes on documents, PDFs, handouts, PowerPoints, or etc. | 3 | 43.73 | 0.411*** | |||

| Access information and resources from the U of M Libraries website on my iPad | 3 | 20.82 | 0.284*** | |||

| Reading e-books or e-textbooks on my iPad | 3 | 24.36 | 0.306*** | |||

| Collaborating Course-related UseAccess social networking sites on my iPad (such as Facebook, Twitter, MySpace, or LinkedIn) | 3 | 12.51 | 0.22** | |||

| Viewing videos on my iPad (You Tube, hulu, Netflix, Ted Talks, etc.) | 3 | 27.26 | 0.324*** | |||

| Listening to music or other audio recordings on my iPad (songs, streaming radio, podcasts) | 3 | 17.80 | 0.262*** | |||

| Video or Text Chat on my iPad (Skype, FaceTime, Facebook chat, etc.) | 3 | 27.66 | 0.327*** | |||

| Creating for Course-related UseCreating documents on my iPad (such as essays, assignments for class, or journal entries) | 3 | 18.58 | 0.268*** | |||

| Taking or editing photos with my iPad | 3 | 21.91 | 0.292*** | |||

| Recording or remixing music or other sounds on my iPad | 3 | 38.27 | 0.384*** | |||

| Recording or editing videos with my iPad | 3 | 17.87 | 0.262*** | |||

| *p ≤.05; **p ≤ .01; ***p ≤ .001 | ||||||

Appendix 3. iPad and educational experience |

||||||

|

df |

χ2 |

Cramer’s V | ||||

| Engaged me in the learning process |

3 |

23.907 |

0.303*** |

|||

| Enriched my learning experience |

3 |

18.895 |

0.270*** |

|||

| Facilitated multiple types of learning activities |

3 |

14.882 |

0.240*** |

|||

| Helped me develop confidence in my understanding of course material |

3 |

18.058 |

0.264*** |

|||

| Made doing course activities more convenient |

3 |

13.011 |

0.224** |

|||

| Helped me develop connections with my classmates |

3 |

8.296 |

0.179* |

|||

| Promoted discussion in class |

3 |

13.183 |

0.225*** |

|||

| Encouraged my active participation |

3 |

24.298 |

0.306*** |

|||

| Helped me develop connections with my instructor |

3 |

30.837 |

0.345*** |

|||

| Made me want to attend class regularly |

3 |

13.441 |

0.227** |

|||

| Increased my excitement to learn |

3 |

13.364 |

0.227** |

|||

| Helped me achieve my learning goals in class |

3 |

17.664 |

0.262** |

|||

| Helped me learn about multimedia |

3 |

4.662 |

0.134 | |||

| Helped nurture a variety of learning styles (visual, auditory, aesthetic) |

3 |

4.007 |

0.125 | |||

| Helped me manage my time |

3 |

20.149 |

0.278*** |

|||

| Provide opportunities to participate in learning activities outside of the classroom |

3 |

9.951 |

0.196* |

|||

| I believe receiving an iPad was important for my learning |

3 |

15.435 |

0.244*** |

|||

| I believe it is important to integrate the iPad into my college life |

3 |

15.731 |

0.246** |

|||

| *p ≤.05; **p ≤ .01;***p ≤ .001 | ||||||

This article was accepted for publication in the International HETL Review (IHR) after a double-blind peer review involving five independent members of the IHR Board of Reviewers and two revision cycles. Accepting editor: Dr Leslie Hitch (Northeastern University, USA), member of the IHR Board of Editors.

Suggested citation

Williams, R. D., Lee, A., Link, A., & Ernst, D. (2014). Minding the gaps: Mobile technologies and student perceptions of technology. International HETL Review, Volume 4, Article 1, https://www.hetl.org/academic-articles/minding-the-gaps-mobile-technologies-and-student-perceptions-of-technology

Copyright 2014 Rhiannon Williams, Amy Lee, Alison Link, & David Ernst

The authors assert their right to be named as the sole authors of this article and to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third party’s rights including copyright. The authors assign to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive license to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The authors also grant a non-exclusive license to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the authors.

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution. By publishing this article, the authors affirms that any original research involving human participants conducted by the authors and described in the article was carried out in accordance with all relevant and appropriate ethical guidelines, policies and regulations concerning human research subjects and that where applicable a formal ethical approval was obtained.