HETL Note:

In this academic article, Dr Tery Taylor discusses the use of video-based technologies as an alternative to face-to-face communications. The author used network analysis to better understand communications under stressful conditions. The results suggest planning is needed when using video-based communications to replace face-to-face dialogue.

Author Bio:

Currently a Senior Lecturer at Northumbria University, Teri’s research profile has seen her engage with and lead projects across academic Learning and Teaching, and in particular has focused upon the influence of individual need and personality upon engagement with technologies within the educational context. With experience in mixed methods research, Teri has developed an international conference and publications profile that reflects her interests. In particular, her recent focus has demonstrated the complexity and interdisciplinary nature of investigations that focus upon individual need rather than institutional drivers. Email: [email protected]

Currently a Senior Lecturer at Northumbria University, Teri’s research profile has seen her engage with and lead projects across academic Learning and Teaching, and in particular has focused upon the influence of individual need and personality upon engagement with technologies within the educational context. With experience in mixed methods research, Teri has developed an international conference and publications profile that reflects her interests. In particular, her recent focus has demonstrated the complexity and interdisciplinary nature of investigations that focus upon individual need rather than institutional drivers. Email: [email protected]

Emotional dialogue via video-mediated communications technologies: A network analysis of influencing factors

Teri Taylor

Northumbria University, UK

Abstract

Video-based communication technologies are not new but the practicalities of the global education market have increasingly encouraged its use for a range of educational activities. However, a failure of research to explore the impact of video-based communications beyond superficial, objective efficacy is felt to potentially risk detrimental effects to the user.

Using Network Analysis, the multi-discipline, influencing factors impacting upon the efficacy of video-based communications under emotive circumstances; such as failing placements or interviews, are explored. Factors influencing efficacy were identified from the fields of Psychology, Sociology, Communications Theory, Linguistics, Technology and Logistics.

Using NodeXL, a network of interlinking influencing factors was generated. Degree, Closeness Centrality and Betweenness Centrality metrics were calculated for nodes within the network. Metrics indicated a primary role of Personality Type, Stress and Non-Verbal Cues as key “brokers” within the network and, therefore, fundamental to communications via video link in context.

Discussion around these factors explores pathways of influence and consequently impact upon the user experience. Personality types displaying neuroticism, low conscientiousness and introversion; reliance upon external resources to combat stress and consequent impacts upon non-verbal communications are shown to potentially be risk factors in using video-based communications under emotive circumstances.

The widespread use of video-based technologies as an alternative to face-to-face communications lacks full exploration of impact in differing contexts. This study illustrates the potential to disadvantage individuals, communicating via video-based technology under stressful conditions. Planning for the use of video-based communications to replace face-to-face dialogue may, therefore, require more in-depth consideration prior to implementation.

Key words: interdisciplinary research; complexity; video-mediated communications; placement-support.

Introduction

Video-based communications technologies (VC) are not new, having been around in a commercial form since the 1970s as part of AT&Ts Picture Phone project (video conferencing guide, 2015). However, with improved infrastructure, faster broadband and the availability of cheaper, more user friendly formats, the use of VC to replace face-to-face activities appears to have seen an increase in popularity. Whilst researchers are reluctant to forecast a sudden global adoption of “consumer level” VC activities (Brandt & Hensley, 2012; Goth, 2011), the practicality of saved time, money and perceived environmental footprint has led to increased exploration and adoption of video-based technologies for a wide range of commercial applications (Armfield, Gray, & Smith, 2012; Ferran & Watts, 2008; Hanna, 2012).

In the last few years researchers have investigated the effectiveness of video-based communications and overall, have found the medium to be successful in producing results similar to face-to-face interactions. As stated in Taylor (2014), however, much of the research focuses upon objective outcome measures of performance i.e. activities that have a tangible outcome such as teaching via video link (Bednar, 2007) or clinical assessment of health via Skype (Rees & Stone, 2005). Until recently, there has been little in-depth investigation into causality and consequently, research has failed to satisfactorily investigate deeper into the impact upon the individual.

Rationale and background literature

In 2009, this author began a series of research projects aimed at evaluating the fitness for purpose of VC in the support of Physiotherapy students, undertaking distant placement experiences. The original feasibility study, aimed at “ironing out” problems, was undertaken under the naive assumption that video communications was a “watered down version” of a face-to-face placement visit. Contrary to expectations, the results from the study illuminated a multitude of questions that challenged perceptions. Further investigation uncovered a complexity of factors influencing amenability towards the medium that had not been previously explored (Taylor, 2014). In particular, it became clear that under emotional circumstances (such as a failing placement) complex collisions between disciplines such as psychology, sociology, communications and media richness theory, and learning technologies impacted upon perceptions of VC in comparison with a face-to-face experience. In contemporary Higher Education, mass educational delivery tends to drive policy making towards a uniform approach. Thus, the findings of this research challenge assumptions that VC can replace face-to-face interaction in this context, and also for a wider range of stressful situations to include interviews and misconduct hearings.

From a literature search using “SPICE” principles (Riesenberg & Justice, 2014), exploration of VC use under emotive circumstances was found to be limited. A number of studies also identify this gap in understanding and advocate further exploration: Deakin and Wakefield (2014) present a reflective case study of two PhD researchers undertaking interviews via Skype. Seen as a potentially stressful circumstance, Deakin and Wakefield explore how Skype interviews are used to replace face-to-face in the current global educational market. Their conclusions recognise limitations in understanding of the wider impact upon the individual of this communications strategy. Robles et al. (2013) investigate perceptions of interviewers and interviewees using Skype. Referring to Media Richness and Procedural Justice Theories, Robles et al. discuss the perceived negative impact of Skype upon opportunities for interviewees to perform well. Their results highlight less favourable evaluations of the interviewer; citing reduced perceived trustworthiness, competence and physical appearance, via Skype. Robles et al. tentatively discuss potential reasons for this in relation to alternations in clarity of verbal and non-verbal message affecting perceptions of interviewer personality and skills. However, they concede that understanding the full reasons behind this requires further exploration and research that includes wider disciplines.

Whilst the Robles et al. utilise “mock” interview experiences and, therefore, may not be entirely representative of reality, it is interesting to note discussions around the impact of Skype upon both cognitive and affective aspects, thus, supporting Taylor (2014) in highlighting links between psychology, communications and sociology in the field of technology.

One of the few papers that seek to explore VC for tutorial support arises from the Open University. Price, Richardson & Jelfs, (2007), explore face-to-face versus online tutoring support with Open University students. Their study uses validated questionnaire scales to evaluate perceived tutor performance, followed by interviews in which perceptions were explored. Their findings challenge online support practices, with results demonstrating a significantly different (negative) perception of tutoring quality by those engaging with online support in comparison with face-to-face support strategies. The authors discount bias caused by inexperienced staff or poorly performing students on the grounds of research rigour.

Although the study fails to explore the factors impacting upon negative perceptions, the nature of support required is cited as being important. The pastoral, as well as academic role of support is proposed as potentially necessitating an element of emotional satisfaction, provided through interaction with the tutor. The lack thereof, through online contact, is suggested to reduce satisfaction. Price et al. (2007) support the role of psychology in communication technology and suggest a need for education into effective communications without the involvement of paralinguistic cues.

Interdisciplinary study

The cited literature demonstrates an increasing willingness to look beyond the technological capabilities of VC towards the interdisciplinary nature of human interactions. Overall, interdisciplinary research in this field is largely ignored and as a result, a rich source of understanding that comes from looking at the cracks between disciplines is missed. Taylor (2014) identifies multiple questions raised within three successive phases of study which highlight differing discipline areas that appear to impact upon the suitability of Skype (or other VC media) for dialogue in context (see Table 1 below).

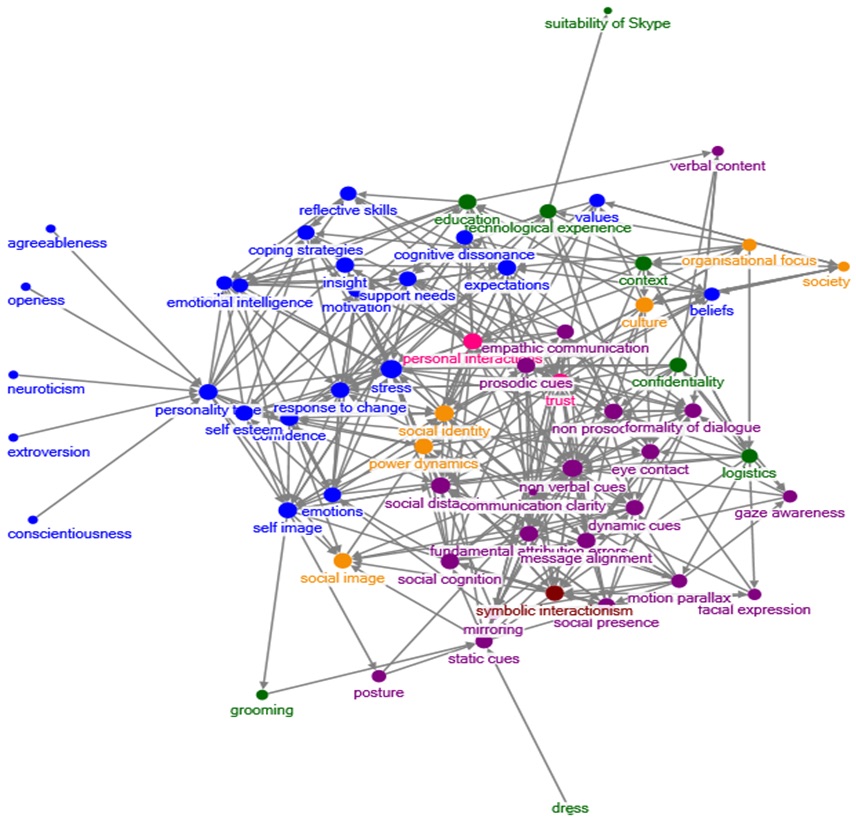

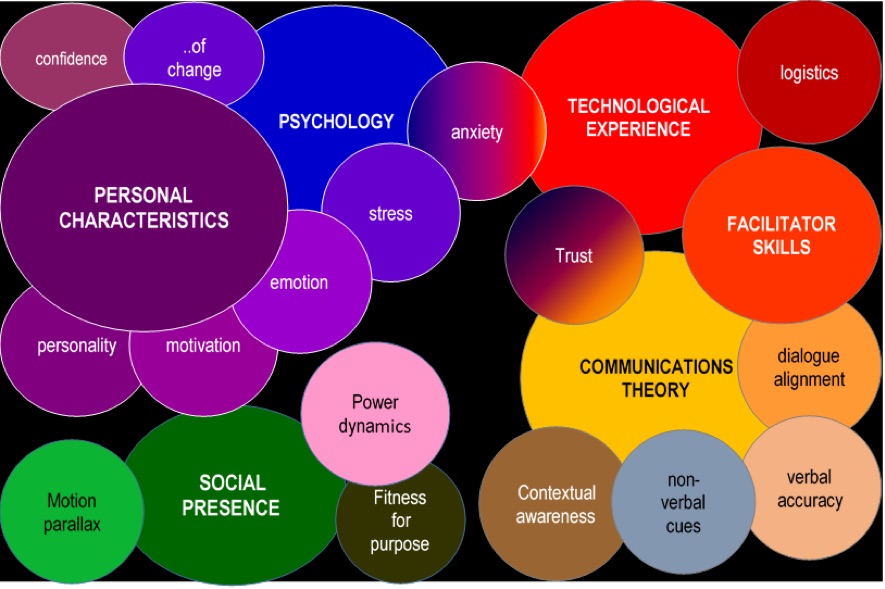

However, whilst discipline areas are loosely identified, the complex “mess” of potential influencing factors (see Figure 1) remains subjective and lacking in a clear analytical framework.

Table 1

Table illustrating issues raised within phases of study, and discipline areas of potential influencing factors

| Project outline | Examples of issues raised in each study (non-exhaustive) | Identified influencing discipline areas |

| Project 1: Pilot project investigating the feasibility of conducting mid-placement support “visits” for Physiotherapy students via VC | · Value of the visit

· Logistics of using VC · Individuality of learners and learner’s needs · Concerns over confidentiality · Differing communication styles |

· Learning technologies

· Logistics · Sociology |

| Project 2: Survey-based project exploring the purpose of mid-placement visits (establishing the role for which VC would be used). | · Concerns over technological use

· Individual learning needs · Role of social interactions in placement progress · Individuality of support need |

· Psychology

· Sociology · Learning technology |

| Project 3: Mixed methods study into differences between face-to-face and VC under emotive circumstances | · Individual communications strategies

· Importance of non-verbal communications · Impact of stress · Social nature of placement interactions · Influence of power dynamics |

· Media richness

· Linguistics · Communications theory · Psychology · Sociology |

![]() Figure 1: (Taylor, 2014). Complexity of influencing factors when considering the application of VC technologies to the support of individual, placement-based students

Figure 1: (Taylor, 2014). Complexity of influencing factors when considering the application of VC technologies to the support of individual, placement-based students

In the context of this author’s original enquiry, understanding these complex interactions is essential in deciding whether VC is fit for purpose. As such, a framework of interdisciplinary research has to be adopted in order to unpick the wider implications of VC practice and explore “plural epistemologies” (Miller & Smith, 2008). Miller et al. (2008) illustrate how understanding plural epistemologies can prevent unnecessary, “non-integrated”, discipline dominated study. Consequently, new knowledge is developed from different thinking, rather than from a combination of expertise and knowledge. From the author’s experience, interdisciplinary research is complex and confusing. In addition, as a lone researcher the lack of in-depth understanding of each discipline area is a challenge in itself. However, it is the recognition of links between, rather than within disciplines that appears to generate the most developmental thinking. The collision of differing concepts and pluralism of epistemologies is felt to be essential in unravelling the complexity of what are often considered to be simplistic concepts.

Inter disciplinary research is not new though it appears to have become more prevalent relatively recently. Raasch,Lee, Spaeth & Herstatt (2013), in evaluating over 300 open source journals, demonstrate the increased frequency of interdisciplinary research within modern publications compared with older work. Whilst their research could be criticised for focusing upon open source, which may tolerate interdisciplinary publications better than more specialist journals, their findings highlight the increase in interdisciplinary studies over a decade. Despite encouragement for interdisciplinary research in Higher Education (Gibb, Haskins, Hannon, & Robertson, 2012) it remains poorly understood and poorly supported. Rafols, Leydesdorff, O’Hare, Nightingale & Stirling (2012) cite the bias of evidence-based journals towards mono-disciplinary research, as effectively limiting interdisciplinary projects, due to impact upon research evaluation activities. Hibbert et al. (2011) discuss the need for specific understanding of interdisciplinary research in doctorate supervision models, and Rjinsoever and Hessle (2011) go on to discuss the lesser impact of interdisciplinary expertise on career development in comparison with single discipline expertise. As such, interdisciplinary approaches continue to result in controversy and challenge.

This paper, through a process of network analysis, aims to aid the reader in understanding the breadth of links between factors influencing perceptions of VC, and the potential for multiple cross-discipline interactions in these factors.

Method

Figure 1 shows the multitude of factors potentially impacting upon perceptions of Skype (Taylor, 2014). The breadth of identified factors was felt to demonstrate how elements of differing discipline areas, could impact upon the experiences of Skype. However, the strength of interaction between factors was unclear, and through attempts to visually illustrate this, it became clear that the links were complex, confusing and loosely resembled a food web network. One of the strengths of interdisciplinary research is felt to be the openness to pragmatic, effective strategies of investigation. The analysis of food webs (within Ecology) utilises the practice of network analysis; a theoretical approach that seeks to understand the input/output models of energy flow through a network. As such, it was felt to differ in focus from the presenting data set that needed to be analysed in terms of links between factors. Conceptually, however, ecological network analysis is analogous to the field of social network analysis (Katz, 1963; Friedkin and Johnsen, 1990: Cited in Johnson et al., 2001) Social network analysis and its subtopic of link analysis aims to investigate hidden links between factors (or nodes) within a network (Johnson et al., 2001)This was felt to mirror the author’s aims in identifying key factors and interactions between factors influencing effective VC under emotive circumstances.

Network Analysis requires that influential factors are plotted as “nodes” in the network. As it was felt that the list of factors identified in previous research was not exhaustive, a scoping exercise was undertaken to establish the size of the field. Taylor (2012) had identified factors that were theoretically situated in six subject discipline areas; Psychology, Sociology, Communications theory, Adult Education, Linguistics and Learning Technologies. The list of potential factors was expanded through exploration of key texts, seminal works and well cited journals in each discipline field. All elements with the potential to impact upon communications via video-based communications were listed as possible factors for network analysis (see Appendix for examples of this process). These factors were then entered onto an Excel spreadsheet as “nodes”. This scoping process identified 60 potential factors from the six subject areas (see Appendix for examples).

Following identification of nodes, uni-directional links between them were created and entered into adjacent columns within the spreadsheet. For example, Personality Type was linked as influencing Coping Mechanisms but the reciprocal link was not listed as Coping Mechanisms do not influence Personality Type. The resulting spreadsheet displayed over 300 unidirectional links (see Appendix for examples). It is acknowledged that the nodes and links identified are, to a degree subjective, and may not be reflective of a full understanding of the intricacies of each field.

However, the complexity of the field negates any attempt at comprehensive explanation of allinfluences and links. This attempt at network analysis aims, therefore, to identify key influential nodes, or those that act most strongly as “brokers” between other nodes i.e. those without which, communications via video link are less effective.

Analysis

The metrics chosen for analysis were “Degree”, “Betweenness Centrality” and “Closeness Centrality” and were based on the work of Hanneman and Riddle (2005). “Degree” recognises those nodes that most frequently influence others, or have power over them: The higher the value, the more influential a node. In-Degree indicates how influenced a particular node is by others, but as this investigation looked for influential factors, out-degree was a more appropriate measure.

Betweenness Centrality identifies nodes that are key to chains of influential links. Like a “broker” in a transaction, nodes with a higher Betweenness Centrality are those that occur most frequently between other, adjacent nodes; an absence of which potentially impedes the link between others and, therefore, the efficacy of communications via the medium.

Closeness Centrality refers to path length between nodes; or the “reach” of that node. Therefore, this provides a measure of whether nodes link with others closely or via more convoluted pathways. Whilst numerous Network Analytical tools exist, many are mathematically orientated; requiring the use of “non-standard” database formats and, therefore, skills not held by the author. Excel’s NodeXL, however, provides a user friendly and familiar interface and was, therefore, used to generate network metrics and visual images.

Results

The NodeXL software generated the subject network and metrics shown in Figure 2 and Table 2 below.

Figure 2: NodeXL network: Representing the complexity of influencing factors and associated links when considering the use of VC media for emotive dialogue.

Table 2

Table showing the overall metrics for the VC network shown in Figure 2

| General network metrics | ||||

| Total Nodes | 63 | |||

| Total Links | 344 | |||

| Network Metric | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Median |

| Out-degree | 1 | 11 | 5.444 | 6.000 |

| Betweenness Centrality | 0.000 | 631.952 | 75.111 | 47.481 |

| Closeness Centrality | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.008 |

NodeXL allows visual representation of networks with node size indicative of chosen metrics. In figure 2, node size indicates Closeness Centrality (larger nodes indicating larger values). There was little difference between Closeness Centrality within the network, with the median value of 0.008. Thus, nodes were comparable in potential strength of influence upon adjoining nodes. Betweenness Centrality and Out-degree values showed greater variation (see Table 3).

Table 3

Metrics generated from network analysis

| Metric

Influencing Factor |

Out-degree | Betweenness Centrality |

| Personality Type | 11 | 631.952 |

| Logistics | 11 | 197.340 |

| Non-verbal cues | 10 | 272.828 |

| Symbolic Interactionism | 10 | 99.177 |

| Stress | 10 | 309.989 |

| Trust | 10 | 166.102 |

| Culture | 11 | 96.966 |

| Emotions | 10 | 51.811 |

| Social Identity | 10 | 159.850 |

| Static Cues | 6 | 209.873 |

Degree

From Table 3 it can be seen that a number of nodes demonstrate high Out-Degree values.

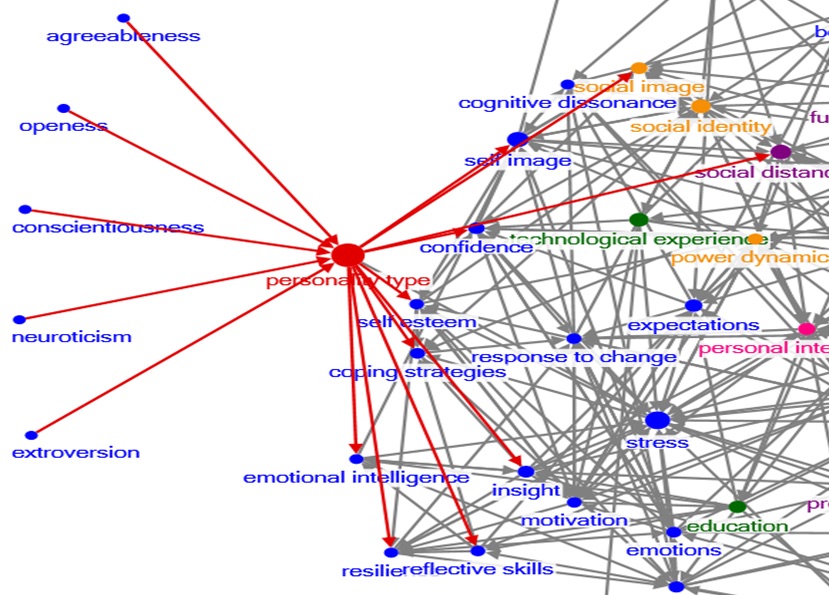

Personality Type, Logistics and Culture were found to have a degree value of 11 (equalling the maximum for the network – see Table 3). These factors are those that influence the most other nodes within this network. Six other nodes were also found to have a Degree value of 10, therefore suggesting high influence. Figure 3 illustrates the interactions with neighbouring nodes, for Personality Type, demonstrating the routes of influence with factors within the network.

Figure 3. Sub network for Personality type illustrating the in-coming and out-going links with other influencing factors.

Betweenness Centrality

The variation in Betweenness Centrality was quite marked, with a minimum and maximum as indicated in Table 2.

Personality Type held a Betweenness Centrality value (n=631.952) considerably higher than other nodes, suggestive of a key role as a “broker” in connecting other influencing factors. Non-verbal Cues, Stress and Static cues (such as dress, grooming, posture etc.) were also found to hold high values well above the mean; 272.828, 309.989 and 209.873 respectively. High Betweenness Centrality values are representative of nodes without which, connection between other nodes would be impeded. Those nodes with highest Betweenness Centrality values, therefore, represent the factors of primary influence within the network.

Combining metrics

When considering the combination of Out-Degree and Betweenness Centrality, it becomes clear that Personality Type is the dominant factor (Out-Degree =11; Betweenness Centrality = 631.952). However, both Non-verbal Cues and Stress also generated high values in both metrics (n=10 and 272.828; and 10 and 309.989 respectively) indicative of a central role within the network. Culture and Logistics can be seen to influence a wide range of other factors (high Degree values) but their lower Betweenness Centrality value suggests less impact upon the overall integrity of the network compared with those nodes obtaining higher values.

The presence of a number of high value metrics for specific nodes, whilst not indicative of importance, is suggestive of the value in further discussion. As Personality Type, Stress and Non-verbal Cues obtain the highest Betweenness Centrality values, and also have high Out-degree values, they will form the basis for further discussion.

Discussion

One of the limitations of this study has been the lack of clear dominance of one “node” over another. In discussions with psychologist and sociologists alike, the influence of different aspects of communication upon others could be debated ad-infinitum. As such, establishing a true network that directs understanding of the dominant nodes is impossible.

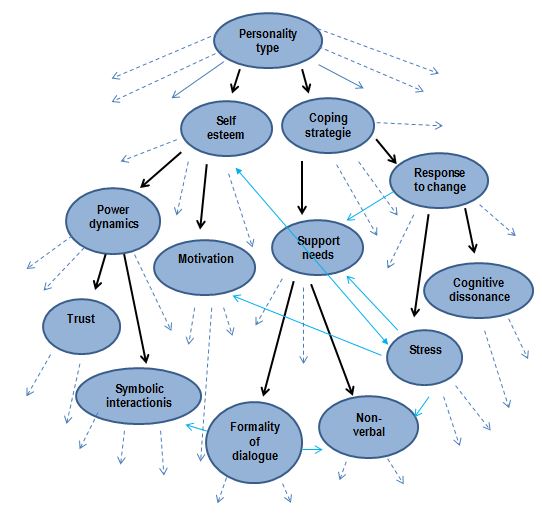

However, as the data above demonstrate, the connections of nodes with one another can be multiple and complex in nature. As such, exploring the routes by which one factor impacts upon perceptions of VC is challenging. Figure 4 below illustrates how understanding one neighbouring nodal link, quickly “snowballs” to needing to understand multiple, complex links.

Figure 4. Diagram highlighting how a pathway between one influencing factor and another can become complex within a small number of degrees

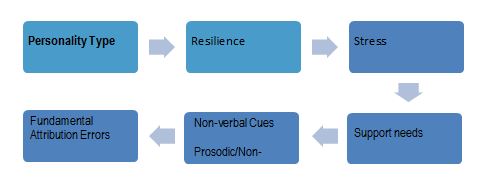

In facilitating users of VC to understand its limitations, pathways of influence need to be understood. By simplifying the Personality Type network, to consider only the pathway between Personality Type and Communications, the complex interactions become clearer (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Simplified network of influence for Personality Type

Exploration of this simplified network, demonstrates the progressive impact of personality type upon communications via the impact upon resilience, its impact upon stress, the impact of stress upon support needs etc. The following discussion fails to make direct links between, for example, resilience and communication. This is intentional in that the issues are complex, with intervening nodes of influence that prevent clear, unidirectional causality. The following discussion attempts to demonstrate the complexity of interactions and, therefore, considerations in planning for the use of video-based communications for potentially emotive dialogue.

Personality Type

The study of Personality Type over the last few decades has been complex. Theories of Personality were numerous until the seminal work of Digman in 1990, which categorised personality traits into five rough characteristics; Conscientiousness; Agreeability; Neuroticism; Extroversion and Openness. These five characteristics (The Five Factor Model (FFM) or Big 5) now form the predominant accepted structure of Personality within research.

The FFM describes the five “normal” characteristics of a healthy adult personality, with these characteristics being further broken down into thirty components that describe an individual’s personality (see Table 4). All of these variables impact upon human-human interaction and as such, indirectly, communication via video-mediated technologies.

Table 4

The “Big 5” personality traits split into their component parts

| Neuroticism | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Extroversion | Openness |

| Anxiety

Angry hostility Depression Self-Consciousness Vulnerability |

Trust

Straightforwardness Altruism Compliance Modesty Tender-Mindedness |

Competence

Order Dutifulness Achievement Striving Self-Discipline Deliberation |

Warmth

Gregariousness Assertiveness Activity Excitements Seeking Positive emotions |

Fantasy

Aesthetics Feelings Ideas Values |

Culture

Of note, whilst Culture does not form part of the pathway being explored in this paper, the potential for it to alter the strength of influences of other factors should not be overlooked. For example, Fearfulness (Neuroticism) may be displayed differently in a culture in which fear is seen as a negative trait compared with one in which it is a more acceptable emotion (McCrae and Costa, 1997). Whilst this paper does not explore Culture as a component of the example pathway, its importance (as shown by its high out-degree value) should not be underestimated and should be recognised in any VC activity in which cultural differences may be of note.

Resilience

Figure 5 illustrates one pathway of links between Personality and Communications, with the first link being between Personality Type and Resilience. Research into links between personality and resilience has increased over the last decade, having been originally hampered by a lack of clear specific measuring tools (Friborg et al., 2005) and a clear definition (Carver, 1998; B. Smith et al., 2008; Tusaie & Dyer, 2004). However, despite multiple definitions, there is a general recognition of the link between resilience in its broadest sense and personality characteristics.

Campbell-Sills, Barlaug, Martinussen, Rosenvinge & Hjemdal (2006) investigated links between the “Big 5” and resilience in young adults, using three validated scales to measure Resilience, Personality and Coping amongst a college student population (n=132). Campbell-Sills, et al.’s results demonstrate negative correlation between Neuroticism and Resilience, and positive correlation between Resilience and Extroversion and Conscientiousness. Their findings echo those of other authors undertaking similar work (Friborg et al., 2005; Smith, 2008; Smith et al., 2006)

Neuroticism

Negative correlation with Neuroticism seems unsurprising, given that neurotic personalities generally exhibit vulnerability to emotions, predominance of negative emotions, poor coping and vulnerability to emotional distress (Ormel, Oldehinkel, & Vollebergh, 2004), whilst the converse low neuroticism individuals display emotional stability and increased ability to cope with stress (Costa and McCrae, 1992: Cited in McCrae, Costa, & Martin, 2005). This suggests that the student with neurotic tendencies is more likely to view a failing placement negatively, to be dominated by negative emotions and to become negatively stressed. The influence of high stress upon communications ability discussed below would suggest the need for assessment of overall resilience, in assisting in identifying those students that would benefit more from face-to-face communications rather than via VC.

Extroversion

Campbell-Sills et al. go on to suggest positive correlation of Resilience with Extroversion and Conscientiousness, citing positive affective style, capacity for interpersonal closeness and high social interaction as the beneficial and “stress combatting” features of these personality types. It is accepted that Extroversion suggests competence in establishing interpersonal closeness, higher social interaction and greater withstanding of stressors, and that Introversion may indicate risk of low resilience and, therefore, susceptibility to stress. However, in the context of placement participation, depending upon the culture, stresses, context etc. of the team itself, access to social interaction will vary. Therefore, the overall lifestyle and social networks of the individual become dominant, with isolated, distant placements presenting more cause for concern for both introverts and extroverts alike.

Conscientiousness

Penley et al. cite the presence of task-orientated coping strategies (more common amongst those high in Conscientiousness) as generating greater resilience. Whilst exploration of Coping Strategies is beyond the scope of this paper, in simplification, Penley et al. suggest that task-orientated coping leads to an effective ability to move beyond stressors and, therefore, develop a higher sense of self-efficacy (Martocchio & Judge, 1997). However, this simplifies a complex process and assumes that the said stressor can be moved beyond. Placements during which students are expected to persist even when individuals or circumstances are threatening, may present stressor that are not possible to move beyond without external help. Therefore, whilst Penley et al. suggest less conscientious students are less able to conceive of self-solving a problem, the conscientious student may be unable to action the conceived solution. This requires appropriate and timely intervention from an external resource; potentially impeded through VC due to the impact of Stress upon Communications (Figure 5).

Response to Stress

Like Resilience, definitions of Stress are widely variable but in general, incorporate aspects of physiology and cognitive function. Stress is a collection of “…physiological responses to perceived or actual threat that challenge or exceed the internal and external coping resources of an individual” (Barkway, 2009, pp.223). Physiologically, the “fight or flight mechanism” (1932: Cited in Ogden, 2012) results in the release of hormones, changes in blood pressure and overall muscle activity, alterations in blood supply and consequent elevation of alertness, energy and aggression (Sajdyk et al., 2008).

Research outlines the role of enhanced social support and engagement as a recommended strategy for improving stress coping responses (Coan, Schaefer, & Davidson, 2006; Heinrichs, Baumgartner, Kirschbaum, & Ehlert, 2003; Insel & Shapiro, 1992). In essence, studies support the benefits of high social skills and openness to interaction, (inherent in extroverts) as mediating the hormonal effects of stress upon the body (Boscarino, 1995; Sayal et al., 2002; Travis, Lyness, Shields, King, & Cox, 2004). In theory, the hypothetical, non-neurotic, extrovert, conscientious student requires less external placement support from university staff, due to their ability to self-regulate stress. The nature of support that they require is likely to be in the form of activities such as assistance in resolving issues, or planning for change or progress. These sorts of activity, as discussed previously, are successful via VC. In contrast, the introverted, neurotic, non-conscientious, failing student appears likely to perceive stress more markedly, and to respond to it more strongly with flight or fight response mechanisms. Practically, this has an impact upon VC via a number of aspects (Figure 5).

Support needs

In considering the failing student typified above, early work by Lazarus (1966; and later followed by Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), illustrates the mechanisms by which an individual identifies their ability to deal with stress. Lazarus’ theory postulates that any individual exposed to a stressful event, goes through two concurrent phases of appraisal; Primary and Secondary. Primary Appraisal evaluates the nature of the stress; positive or negative; relevant or irrelevant; threatening or harmful.

For the neurotic student, the ability to perceive a stress as relevant or irrelevant may not be strong due to a lack of objectivity. Combined with a lack of conscientiousness the student is at risk of perceiving stress inaccurately, potentially to an elevated degree, or ironically not identifying a stress that is necessary for personal development. In practical terms these are the students who may need assistance in identifying their learning needs, their strengths and weaknesses and in developing reflective skills. Therefore, the very nature of communications moves from information sharing to collaborative and supportive dialogue, potentially necessitating access to shared paperwork; which Taylor (2014) identifies as sub-optimal via VC.

Lazarus (1966) goes on to define Secondary Appraisal as a cognitive assessment process, evaluating one’s ability to manage/respond to the identified stressor. This secondary element leads to identification of internal and external resources that are available to the individual in initiating a response. Internal resources include personality attributes such as resilience; locus of control and self-efficacy (related to conscientiousness; Caprara, Vecchione, Alessandri, Gerbino & Barbaranelli, 2011); and optimism and pessimism (related to extroversion; Sharpe, Martin & Roth,, 2011).

The hypothetical student outlined above, is likely to suffer from a predominance of external locus of control, poor self-efficacy and a preponderance of pessimism. Consequently, they are unlikely to perceive sufficient internal resources to mediate an effective response to stress. Thus, support needs become focused upon the external resource (academic tutor or clinical educator) as the primary solution to the failing placement.

Where external locus of control dominates, responsibility for failure of the placement is likely to be perceived as being external to the student. In these instances, not only does the student struggle to attribute failure to their own actions (Rotter, 1966), but the clinical educator may also become the primary source of stress. As such, the role of clinical educator as an external resource is negated and the importance of communications with an academic tutor, potentially via VC, is elevated. Combined with low self-efficacy and, therefore, low belief in capability (Bandura, 2011), and pessimism, the student becomes entirely reliant upon the external resource and is unable to actively utilise internal mechanisms of coping. Under these circumstances, effective communication becomes essential not only to the placement success but to the wellbeing of the individual, and the limitations of VC in facilitating this need to be considered.

Communications strategies and non-verbal cues

Under the failing conditions outlined above, the role of the academic tutor may become multiple: As a familiar face, the tutor may be expected to provide an emotional or “esteem support” role (Cobb, 1976), developing the confidence and self-belief of the failing student. As academic tutor, the developmental needs of the student are considered. As a professional, the tutor’s role may necessitate mediation between student and clinical team. As such, communications need to be not only effective in delivering a message but also in developing effective and appropriate working relationships with both parties.

Within human interaction, interpersonal relationships are fundamental to support activities and rely upon the generation of a degree of empathy between participants (Arizmendi, 2011; Goldman, 2009). When using VC, alterations in non-verbal cues can challenge the trusting, empathic relationship necessary to support a failing student. Therefore, non-verbal cues become a fundamental broker for effective communication.

Changes in communications strategies as a result of VC are well documented. In particular, limitations in eye contact are cited as problematic, leading to altered interaction (Kappas & Krämer, 2011). For example, the presence of a camera tends to encourage attempts to maximise eye contact in order to maintain “good” communications. However, normal interaction involves short periods of eye contact followed by other periods of gaze that occurs in the general direction of the recipient (Gale & Monk, 2000), therefore, an increase in duration of eye contact may be perceived as confrontational. In contrast, webcam positioning can result in decreased eye contact or confusion over gaze direction. Exacerbated in distracting environments, a loss of eye contact or gaze awareness may be perceived as dishonesty or discomfort with the dialogue and has been seen to raise concerns over confidentiality and trust (Taylor, 2012).

In the context of supporting a failing student, trust is fundamental to the development of a supportive relationship (Linell & Marková, 2013). In the case of the neurotic student, lack of trust may further exacerbate perceptions of victimisation/lack of responsibility for the failing nature of the placement, and may encourage defensiveness or aggression towards the supporting tutor.

Further complicating access to non-verbal cues via VC, is the limitation in image size and resolution. Early work by Clark and Brennan (1991) discusses the social nature of dialogue: Normal communications involve complex patterns of interruptions that are unpredictable, dependent upon circumstance and supported by non-verbal cues. Subtle head movements, for example, may be used to indicate opportunities for interruption or cessation of speech. However, via VC these motions are particularly difficult to gauge; a problem which is emphasised when the view image is either just facial (which maximises facial expression but prevents visual access to wider non-verbal cues) or full body (where the subtleties of eye contact or facial expression may not be available).

In addition, a lack of ability to view the full spectrum of non-verbal cues may prevent full understanding of the dialogue sub-text. This becomes particularly important when dealing with a student whose method of coping with stress incorporates an element of denial (Barkway, 2009). A lack of symptoms of stress does not mean that stress is not present and Miller and Smith (2012) argue that a lack of symptoms needs exploring to avoid ignorance of a camouflaged underlying problem. Subtle body movements such as toe tapping, fidgeting, or lack of clear eye contact may be used under face-to-face circumstances to indicate underlying discomfort (Krauss, 2002) and, therefore, identify underlying issues. VC under these circumstances is limited.

The generation of an empathic relationship is also based upon the effective visualization and use of body language; using mirrored body language, facial expression and verbal communications strategies (Arizmendi, 2011) to ensure accuracy of message. For the supporter to fully understand the emotional wellbeing and response of the supportee, and for the supportee to be left with no ambiguity of message that may foster mistrust, inaccuracies in response or non-verbal communications need to be avoided.

Carr,Iacoboni, Dubeau, Mazziotta & Lenzi, (2003) discuss the role of facial mirroring in perceptions of emotion. Observing individuals engaging in emotive dialogue under MRI scan, activity in the Amygdala (an area of the brain critical in emotional behaviour) was seen in the recipient, mirroring the emotions of the speaker. Carr et al.’s work suggests that mirroring of facial expression essentially facilitates the recipient experiencing the emotions of the speaker, thus, enabling a more appropriate response. Research into the development of interactive avatars emphasis both facial expression and wider, non-verbal cues as being important in generating perceptions of interpersonal relationships (Fabri, Moore & Hobbs, 2004; Fabri, Moore & Hobbs, 1999). The use of “matching” verbal, facial and non-verbal messages in generating full clarity of meaning is referred to as alignment and is thought to be more important within emotional interaction, than the clarity of either verbal or non-verbal message alone (Bachan, 2011; Pickering & Garrod, 2004).

Understanding non-verbal cues enables appreciation of the impact of VC upon effective communications. Whilst unimportant for information dissemination, fact finding or task completion, in which interpersonal relations are less crucial, effective alignment of non-verbal and verbal cues becomes particularly pertinent when supporting the hypothetically neurotic, non-conscientious and introverted, failing student. Due to their lack of resilience, support needs are likely to require a greater contribution of input from the supporting tutor, acting as an external coping resource with a multitude of roles. As such, communication needs to be empathic and effective with a lack of ambiguity and non-verbal cues become central to efficacy.

Conclusion

Under emotive circumstances the ability of VC to act as an effective and appropriate communications medium is challenged. Previous work has questioned the fitness for purpose of VC in this context but a failure to clarify the key influencing factors has hindered understanding of the reasons behind limitations in the medium. Network analysis has generated a visual representation of the interconnections between a range of subject disciplines; Psychology, Sociology, Communications, Linguistics, Technology and Logics. Network metrics suggest Personality Type, Stress and Non-verbal cues as being potentially important to predicting amenability of an individual towards communications via VC under emotive circumstances. Therefore, a failure to consider these factors when planning for VC use, risks inappropriate application in this context.

The findings of this study do not aim to provide a definitive guide to the VC user, but to encourage users to consider factors such as personality type, stress levels or the importance of clarity in communications when choosing between face-to-face and video-based strategies. For contexts such as failing placements, interviews or misconduct hearings for example, where emotions are high and clear communications are essential, it is suggested that VC may be inappropriate, and may exacerbate already stressful events. In this context, VC offers a sub-optimal communications approach, particularly for those individuals with negative personality traits or experiencing higher levels of stress.

Limitations

Due to the wide interdisciplinary nature of this research project, the author’s understanding of each subject area is limited to that achieved through basic texts, key seminal work and key contemporary literature. As such, it is acknowledged that the breadth of nodes identified within the network may be subjective. In addition, a lack of ability to define the strength of links between nodes in the network, means that the specific importance of factors is difficult to gauge. The generated network allows analysis of factors sufficient to identify probable key influential elements and to follow the pathways of links between them. The strength of influence of each element however, is likely to vary with the individual concerned. As such, it is an understanding of the complexity of links, and the potential for multiple discipline areas to contribute to the efficacy of non-standard communications strategies, that is encouraged in readers. It is hoped that this paper will, therefore, encourage discussion and consideration of wider factors in planning VC use in practice.

Future recommendations

In order to fully appreciate the complexity of influences upon communications in this manner, interdisciplinary research using a wide team of experts in their fields in order to generate a comprehensive database of nodes is suggested.

References

Arizmendi, T. G. (2011). Linking mechanisms: Emotional contagion, empathy, and imagery. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 28(3), 405-419. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.2.234.10.1037/0012-1649.25.6.954.

Armfield, N. R., Gray, L. C., & Smith, A. C. (2012). Clinical use of Skype: a review of the evidence base. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 18(3), 125-127.

Bachan, J. (2011). Modelling semantic alignment in emergency dialogue. Proceedings of 5th LTC, 2011, 324-328.

Bandura, A. (2011). Social cognitive theory. Handbook of social psychological theories, 349-373.

Barkway, P. (2009). Psychology for health professionals: Elsevier Australia.

Bednar, E. D., Hannum, W.M., Firestone, A., Silveira, A.M., Cox, T.D and Proffit, W.R. (2007). Application of distance learning to interactive seminar instruction in orthodontic residency programs. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics, 132(5), 586-594.

Boscarino, J. A. (1995). Post‐traumatic stress and associated disorders among Vietnam veterans: The significance of combat exposure and social support. Journal of traumatic stress, 8(2), 317-336.

Brandt, R., & Hensley, D. (2012). Teledermatology: the use of ubiquitous technology to redefine traditional medical instruction, collaboration, and consultation. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology, 5(11), 35.

Campbell-Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(4), 585-599.

Caprara, G. V., Vecchione, M., Alessandri, G., Gerbino, M., & Barbaranelli, C. (2011). The contribution of personality traits and self‐efficacy beliefs to academic achievement: A longitudinal study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(1), 78-96.

Carr, L., Iacoboni, M., Dubeau, M.-C., Mazziotta, J. C., & Lenzi, G. L. (2003). Neural mechanisms of empathy in humans: A relay from neural systems for imitation to limbic areas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(9), 5497-5502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0935845100.

Carver, C. S. (1998). Resilience and thriving: Issues, models, and linkages. Journal of social issues, 54(2), 245-266.

Clark, H. H., & Brennan, S. E. (1991). Grounding in communication. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine & S. D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition. Washington DC: APA.

Coan, J. A., Schaefer, H. S., & Davidson, R. J. (2006). Lending a hand social regulation of the neural response to threat. Psychological science, 17(12), 1032-1039.

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic medicine, 38(5), 300-314.

Deakin, H., & Wakefield, K. (2014). Skype interviewing: reflections of two PhD researchers. Qualitative Research, 14(5), 603-616.

Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual review of psychology, 41(1), 417-440.

Fabri, M., Moore, D., & Hobbs, D. (2004). Mediating the expression of emotion in educational collaborative virtual environments: an experimental study. Virtual Reality, 7(2), 66-81. doi: 10.1007/s10055-003-0116-7.

Fabri, M., Moore, D. J., & Hobbs, D. J. (1999). The emotional avatar: non-verbal communication between inhabitants of collaborative virtual environments Gesture-Based Communication in Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 269-273): Springer.

Ferran, C., & Watts, S. (2008). Videoconferencing in the field: A heuristic processing model. Management Science, 54(9), 1565-1578.

Friborg, O., Barlaug, D., Martinussen, M., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Hjemdal, O. (2005). Resilience in relation to personality and intelligence. International journal of methods in psychiatric research, 14(1), 29-42.

Gale, C., & Monk, A. (2000). Where am I looking? The accuracy of video-mediated gaze awareness. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 62(3), 586-595. doi: 10.3758/bf03212110.

Gibb, A., Haskins, G., Hannon, P., & Robertson, I. (2012). Leading the Entrepreneurial University: Meeting the Entrepreneurial Development Needs of Higher Education (2009, updated 2012).

Goldman, A. I. (2009). Mirroring, Simulating and Mindreading. Mind & Language, 24(2), 235-252. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0017.2008.01361.x.

Goth, G. (2011). Huge growth for video telephony? skeptics wary of predicted data crunch. Internet Computing, IEEE, 15(3), 7-9.

Hanna, P. (2012). Using internet technologies (such as Skype) as a research medium: a research note. Qualitative Research, 12(2), 239-242.

Hanneman, R. A., & Riddle, M. (2005). Introduction to social network methods: University of California Riverside.

Heinrichs, M., Baumgartner, T., Kirschbaum, C., & Ehlert, U. (2003). Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biological psychiatry, 54(12), 1389-1398.

Hibbert, K., Kinsella, E. A., Lingard, L., McKenzie, P., Pitman, A., Vanstone, M., & Wilson, T. (2011). Interdisciplinary Doctoral Supervision Teams: Working Together within, between, and outside of Disciplinary Boundaries of Knowledge.

Insel, T. R., & Shapiro, L. E. (1992). Oxytocin receptor distribution reflects social organization in monogamous and polygamous voles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 89(13), 5981-5985.

Johnson, J. C., Borgatti, S. P., Luczkovich, J. J., & Everett, M. G. (2001). Network role analysis in the study of food webs: an application of regular role coloration. Journal of Social Structure, 2(3), 1-15.

Kappas, A., & Krämer, N. C. (2011). Face-to-face communication over the Internet: emotions in a web of culture, language, and technology Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Krauss, R. M. (2002). The Psychology of Verbal Communication. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. from http://www.columbia.edu/~rmk7/PDF/IESBS.pdf.

Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York, NY, US: McGraw-Hill.

Linell, P., & Marková, I. (2013). Dialogical Approaches to Trust in Communication: IAP.

Martocchio, J. J., & Judge, T. A. (1997). Relationship between conscientiousness and learning in employee training: mediating influences of self-deception and self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(5), 764.

McCrae, R. R., Costa, J., Paul T, & Martin, T. A. (2005). The NEO–PI–3: A more readable revised NEO personality inventory. Journal of personality assessment, 84(3), 261-270.

Miller, L., & Smith, A. (2012). Six myths about stress. Retrieved 24/09/12, from http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/stress-myths.aspx.

Ormel, J., Oldehinkel, A. J., & Vollebergh, W. (2004). Vulnerability before, during, and after a major depressive episode: a 3-wave population-based study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(10), 990-996.

Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2004). Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27, 169-226.

Price, L., Richardson, J. T. E., & Jelfs, A. (2007). Face‐to‐face versus online tutoring support in distance education. Studies in Higher Education, 32(1), 1-20. doi: 10.1080/03075070601004366.

Raasch, C., Lee, V., Spaeth, S., & Herstatt, C. (2013). The rise and fall of interdisciplinary research: The case of open source innovation. Research Policy, 42(5), 1138-1151.

Rafols, I., Leydesdorff, L., O’Hare, A., Nightingale, P., & Stirling, A. (2012). How journal rankings can suppress interdisciplinary research: A comparison between innovation studies and business & management. Research Policy, 41(7), 1262-1282.

Rees, C., & Stone, S. (2005). Therapeutic alliance in face-to-face versus video conferenced psychotherapy. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 36, 649-653.

Riesenberg, L. A., & Justice, E. M. (2014). Conducting a successful systematic review of the literature, part 1. Nursing2014, 44(4), 13-17.

Robles, P. F., J. Sears, G., Zhang, H., H. Wiesner, W., D. Hackett, R., & Yuan, Y. (2013). A comparative assessment of videoconference and face-to-face employment interviews. Management Decision, 51(8), 1733-1752.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 80(1), 1.

Sajdyk, T. J., Johnson, P. L., Leitermann, R. J., Fitz, S. D., Dietrich, A., Morin, M., Shekhar, A. (2008). Neuropeptide Y in the amygdala induces long-term resilience to stress-induced reductions in social responses but not hypothalamic–adrenal–pituitary axis activity or hyperthermia. The Journal of Neuroscience, 28(4), 893-903.

Sayal, K., Checkley, S., Rees, M., Jacobs, C., Harris, T., Papadopoulos, A., & Poon, L. (2002). Effects of social support during weekend leave on cortisol and depression ratings: a pilot study. Journal of affective disorders, 71(1), 153-157.

Sharpe, J. P., Martin, N. R., & Roth, K. A. (2011). Optimism and the Big Five factors of personality: Beyond neuroticism and extraversion. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(8), 946-951.

Smith, B., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International journal of behavioral medicine, 15(3), 194-200.

Smith, T. (2006). Personality as risk and resilience in physical health. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 227-231.

Taylor, T. (2014). Considering complexity in simple solutions: What’s so complicated about Skype? International Journal of Systems and Societies, 1(1), 35-52.

Travis, L. A., Lyness, J. M., Shields, C. G., King, D. A., & Cox, C. (2004). Social support, depression, and functional disability in older adult primary-care patients. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry, 12(3), 265-271.

Tusaie, K., & Dyer, J. (2004). Resilience: A historical review of the construct. Holistic nursing practice, 18(1), 3-10.

van Rijnsoever, F. J., & Hessels, L. K. (2011). Factors associated with disciplinary and interdisciplinary research collaboration. Research Policy, 40(3), 463-472.

Video Conferencing Guide. (2015). History of Video Conferencing. Retrieved 04/05/15, from http://www.video-conferencing-guide.org/history-of-video-conferencing.html.

Appendix

| id | to_id | from_id |

| … | ||

| 7 | technological experience | eye contact |

| 8 | confidence | eye contact |

| 10 | confidence | self image |

| 18 | personality type | resilience |

| 25 | openness | personality type |

| 30 | values | social identity |

| 38 | beliefs | cognitive dissonance |

| 43 | personal interactions | social identity |

| 60 | emotions | stress |

| 61 | social identity | personal interactions |

| 64 | social identity | dynamic cues |

| 65 | social identity | static cues |

| 71 | organisational focus | technological experience |

| 78 | culture | values |

| 79 | culture | beliefs |

| 92 | motivation | expectations |

| 253 | facial expression | communications clarity |

| 255 | facial expression | mirroring |

| 256 | gaze awareness | trust |

| 261 | social presence | mirroring |

| 276 | reflective skills | coping strategies |

| 286 | support needs | non prosodic cues |

| 287 | support needs | non-verbal cues |

| 295 | logistics | confidentiality |

Table illustrating examples of created nodes and links. Column 2 indicates influencing nodes, column 3 indicates links to other nodes. The table does not illustrate all links generated.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Dr. Anna Jones who as always has been instrumental in guiding my development and thought processes and in reducing my tangents.

This academic article was accepted for publication in the International HETL Review (IHR) after a double-blind peer review involving three independent members of the IHR Board of Reviewers and one revision cycles. Accepting editor: Dr Charlynn Miller

Suggested citation:

Taylor, T. (2018). Emotional dialogue via video-mediated communications technologies: A network analysis of influencing factors. International HETL Review, Volume 8, Article 8, https://www.hetl.org/emotional-dialogue-via-video-mediated-communications-technologies-a-network-analysis-of-influencing-factors

Copyright 2018 Tery Taylor

The author(s) assert their right to be named as the sole author(s) of this article and to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third party’s rights including copyright. The author(s) assign to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive licence to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The author(s) also grant a non-exclusive licence to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the author(s).

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution. By publishing this article, the author(s) affirms that any original research involving human participants conducted by the author(s) and described in the article was carried out in accordance with all relevant and appropriate ethical guidelines, policies and regulations concerning human research subjects and that where applicable a formal ethical approval was obtained.