HETL note: We are pleased to present “Exploring Tensions between English Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices in Teaching Writing” – an academic article by Dr. Tagesse Abo Melketo. The study investigates how teachers’ beliefs and attitudes towards teaching academic writing translates into classroom practice and reveals some of the reasons for the mismatch between ‘intended’ and ‘real’ teaching. The author who is an expert in the area discusses the implications of the study with respect to improving language and writing teaching by adopting innovative teaching styles. You may submit your own article on the topic or you may submit a “letter to the editor” of less than 500 words (see the Submissions page on this portal for submission requirements).

Author bio: Tagesse Abo Melketo is an English Language instructor at the Faculty of Social Science and Humanities, Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia. His academic careers include senior lecturer position, assistant faculty deanship, and the role of executive director of a secondary school. Tagesse’s research area is language education with a focus on learning behavior. His publications include a book, Writing Reluctance: Students’ Characteristics and Perceptions (VDM Publishing, Saarbrucken, Germany), and scholarly articles in the refereed academic journal, Asian EFL Journal Quarterly. At present Tagesse is involved in teaching, student advising and research; he is also the director of the External Relations Office of Wolaita Sodo University. Tagesse directs joint development projects funded by bilateral and multilateral donor agencies in multicultural contexts where he contributes from his significant international experience. Tagesse can be contacted at: Wolaita Sodo University, P.O. Box 138, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia. Phone: +251912033352, e-mail: [email protected]

Author bio: Tagesse Abo Melketo is an English Language instructor at the Faculty of Social Science and Humanities, Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia. His academic careers include senior lecturer position, assistant faculty deanship, and the role of executive director of a secondary school. Tagesse’s research area is language education with a focus on learning behavior. His publications include a book, Writing Reluctance: Students’ Characteristics and Perceptions (VDM Publishing, Saarbrucken, Germany), and scholarly articles in the refereed academic journal, Asian EFL Journal Quarterly. At present Tagesse is involved in teaching, student advising and research; he is also the director of the External Relations Office of Wolaita Sodo University. Tagesse directs joint development projects funded by bilateral and multilateral donor agencies in multicultural contexts where he contributes from his significant international experience. Tagesse can be contacted at: Wolaita Sodo University, P.O. Box 138, Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia. Phone: +251912033352, e-mail: [email protected]

Krassie Petrova and Patrick Blessinger

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Exploring Tensions between English Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices in Teaching Writing

Tagesse Abo Melketo

Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia

Abstract

This article presents results of a case study examining relationships between instructors’ pedagogical beliefs and teaching practices with respect to university writing instruction. The exploration sought to outline the teachers’ beliefs about, and classroom practices in, teaching academic writing. Participants included three instructors of English working at Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia. Data were collected over a four-month period using successive interviews and observations of instructors’ actual classroom practices. From the interviews, it was apparent that teachers’ beliefs about teaching the writing process and appropriate writing strategies for enhancing and supporting the development of students’ writing skill were constant. In the study, however, teachers’ classroom practices did not always correspond to their beliefs. The reasons for a mismatch would seem to be highly complex, but there was evidence to suggest that teachers’ ability to teach related to their beliefs was influenced mainly by contextual factors such as class time, students’ expectations, teaching the test rather than teaching the subject and focusing on classroom management concerns. Some implications of this study for language teacher education are also discussed.

Keywords: Teacher cognition; teacher beliefs; teacher education; writing instruction; process writing; second language teaching

INTRODUCTION

In the last two decades, the study of teachers’ beliefs has received attention from many researchers in the field of language teaching. The relationship between teachers’ beliefs and their classroom practices has been one thread of the work. More specifically, researchers have been interested in the extent to which teachers’ stated beliefs correspond with what they do in the classroom, and there is evidence that the two do not always coincide (Gebel & Schrier, 2002). Such differences have been viewed as unwanted or negative phenomenon and a handful of studies (e.g., Tayjasanant & Barnard, 2010) have described it using terms such as incongruence, inconsistency, and discrepancy. In this article, I argue for a more positive perspective on such differences, conceptualizing the phenomena as ‘tensions’, that is, “divergences among different forces or elements in the teacher’s understanding of the… subject matter…” (Borg & Phipps, 2009, p. 380). This study specifically explores divergence between what English language teachers ‘say’ and ‘do’ in teaching writing. By exploring the reasons for this mismatch, I provide insight into deeper tensions among competing beliefs that teachers hold.

Significant contributions to understanding the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and practices have been made in first language (L1) education contexts. English-speaking countries such as the United Kingdom (Phipps & Borg, 2009; Kuzborska, 2011) and a Spanish-speaking country (Lacorte & Canabal, 2005) are examples.. However, studies investigating teachers’ cognition in foreign language (FL) contexts have been limited (Borg, 2003, 2006). Further, studies of this type have so far mainly been conducted either in English as a second language (ESL) settings, such as Singapore (Ng & Farrell, 2003) and Hong Kong (Andrews, 2003), or in Western English as a foreign language (EFL) contexts (Borg, 2009), but not very much in non-Western EFL countries, such as Ethiopia. Moreover, very limited studies to date have focused on the relationships between university teachers’ theoretical orientations and teaching practices with respect to writing instruction in EFL. Thus, I provide some contextual background to Ethiopian education, especially the status of English.

The Ethiopian education system follows an 8-4 system, that is, eight years of primary education and four years of secondary education. Primary education has two distinctive stages: first cycle (G1-G4) and second cycle (G5-G8). Similarly, secondary education is staged as general secondary (G9 and G10) and preparatory education (G11 and G12). Students who qualify for preparatory education and who fulfill the requirements to apply for university studies are enrolled in universities. English plays an important role in Ethiopian education: It is widely considered an ‘intellectual language’. In many regions, starting from late primary school (G7 and G8), English is used as a medium of instruction for all subjects except local languages. Success in higher education usually depends on academic English competence, part of which is competence in English writing. English teachers are required to develop students’ academic and professional communicative competence, enabling them to effectively communicate in academic and further professional contexts. By examining the links between personal theories and practices, this study intends to assist teachers to become effective professionals and increase students’ achievement in core subject areas.

The Ethiopian education system follows an 8-4 system, that is, eight years of primary education and four years of secondary education. Primary education has two distinctive stages: first cycle (G1-G4) and second cycle (G5-G8). Similarly, secondary education is staged as general secondary (G9 and G10) and preparatory education (G11 and G12). Students who qualify for preparatory education and who fulfill the requirements to apply for university studies are enrolled in universities. English plays an important role in Ethiopian education: It is widely considered an ‘intellectual language’. In many regions, starting from late primary school (G7 and G8), English is used as a medium of instruction for all subjects except local languages. Success in higher education usually depends on academic English competence, part of which is competence in English writing. English teachers are required to develop students’ academic and professional communicative competence, enabling them to effectively communicate in academic and further professional contexts. By examining the links between personal theories and practices, this study intends to assist teachers to become effective professionals and increase students’ achievement in core subject areas.

The Concept of Teachers’ Beliefs

Mansour (2009) argued that beliefs are one of the most difficult concepts to define. Although the educational literature has paid great attention to teachers’ beliefs, there is still no clear definition of belief as a term (Savaci-Acikalin, 2009). As Pajares (1992) argued, “the difficulty in studying teachers’ beliefs has been caused by definitional problems, poor conceptualizations, and differing understandings of beliefs and belief structures” (p.307). He suggested that researchers need agreement on meaning and conceptualization of belief.

Researchers have defined the term, beliefs, in different ways. For example, Pajares (1992), in his literature review, defined belief as an “individual’s judgment of truth or falsity of a proposition, a judgment that can only be inferred from a collective understanding of what human beings say, intend, and do” (p.316). According to Aguirre and Speer (2000), current definitions of teacher beliefs in the educational literature focus on how teachers think about the nature of teaching and learning. In this context, beliefs are defined as “conceptions” (Thompson, 1992, p. 132), world views, and “mental models” that shape learning and teaching practices (Ernest, 1989, p. 250).

Despite the difficulties related to clearly defining this “messy construct” (Pajares, 1992, p. 307), Kuzborska (2011) proposed that all teachers hold beliefs about their work, their students, their subject matter, and their roles and responsibilities. Borg (2003, 2006) categorized teachers’ educational beliefs within their broader belief systems. In Borg’s view, beliefs can be narrowed and categorized. For example, educational beliefs about the nature of knowledge, perceptions of self and feelings of self worth, and confidence to perform certain tasks, are categories. Following these recommendations, this study focused specifically on teachers’ educational beliefs about teaching and learning the beliefs teachers have about how English writing skill is taught, and factors influencing the implementation of these beliefs in classroom practice. The term beliefs here refer to teachers’ pedagogic beliefs (Borg 2001), which are related to convictions about language and the teaching and learning of it. These beliefs are manifested in teachers’ approaches, selection of materials, activities, judgments, and behaviors in the classroom.

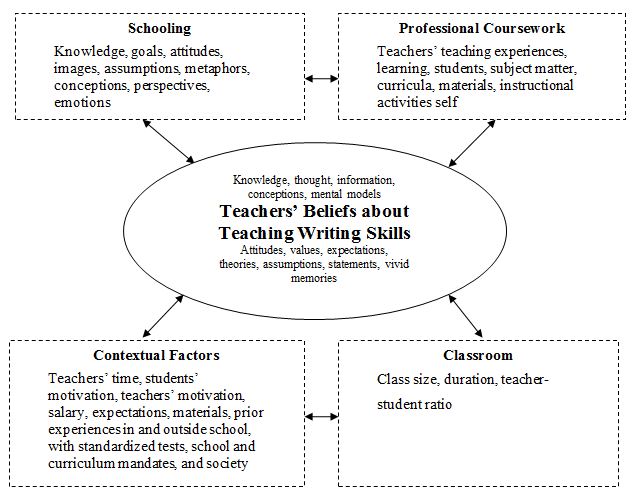

The researcher adapted the following diagrammatical representation of the conceptual framework of the nature of teachers’ writing instruction beliefs and factors influencing the manifestation of these beliefs in classroom practices.

(Adapted from Borg, 2003)

Figure 1: A model of teachers’ writing instruction beliefs and practices

Several studies have examined relationships between teachers’ beliefs and their practices. However, perhaps partly because of the variety of definitions in the literature, relationships between teacher beliefs and practices have been questioned. Some researchers in science and mathematics reported a high degree of agreement between teacher beliefs and the practice of teaching (Aguirre & Speer, 2000; Ernest, 1989; Standen, 2002; Thompson, 1992) while others have identified some inconsistencies (Kynigos & Argyris, 2004; Lfebvre, Deaudelin & Loiselle, 2006; Zembylas, 2005).

Findings from some recent studies (e.g., Savasci-Acikalin, 2009; Mansour, 2008) illustrated that relationships between teacher beliefs and practices were controversial and complex. Results suggest that researchers should question their common assumptions because several factors are believed to contribute to the complexity of these relationships. After a review of research, Borg (2003) commented that factors such as parents, principals’ requirements, the school, society, curriculum mandates, classroom and school lay-out, school policies, colleagues, standardized tests and the availability of resources may hinder language teachers’ ability to carry out instructional practices reflecting their beliefs. Thus, contextual factors need to be part of any analysis of the relationship between teacher beliefs and practices. Others (e.g., Phipps, 2010; Phipps & Borg, 2007, 2009) have claimed that the dichotomy of beliefs and practices may stem from teachers’ professional course work and prior experiences in and outside of school with teaching, learning experiences, students, or their activities.

This study examined the relationship between language teachers’ elicited beliefs and their classroom work through the analysis of interview responses and observed teaching practices. From this point forward, the term teachers refer to language instructors, particularly instructors of writing courses at an Ethiopian university.

STUDY DESIGN

In order to gain insights into links between teachers’ theoretical orientations toward academic writing instruction and their teaching practices, the study posed the following research questions:

• What beliefs do teachers hold about teaching writing? To what extent are these beliefs internally consistent?

• To what extent are teachers’ beliefs about writing instruction congruent with their observed practices?

• What factors may have influenced the teachers’ approach not to teach writing in line with their beliefs?

Study Participants

The study lasted one semester (four months) at an Ethiopian university and involved three EFL teachers. Each teacher had been teaching English for about three years at the university at the time of data collection (March to- June 2011). The teachers’ English teaching experiences in general (including English teaching at the university) ranged from 3 to 6 years. Each teacher held a university master’s degree (M.A.) issued by an Ethiopian university after two academic years of study in postgraduate courses and completion of a master’s thesis. Each was qualified in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) with an MA degree in Teaching English as Foreign Language (TEFL). However, none of the teachers had initial, direct training in composition studies, rhetoric or applied linguistics.

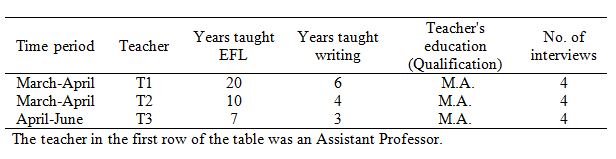

Participants were a volunteer sample of three EFL instructors working at the University of Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia. Ten instructors, out of 30 academic staff members in the department of English, volunteered to participate in the research in response to a solicitation letter circulated by the department head. The researcher purposively selected three instructors who had experience teaching writing, and informed those chosen about the general purposes of the study. Table 1 summarizes the backgrounds of the instructors who volunteered, as well as periods of time when interview data were collected in their four-month EFL courses.

Table 1. Interviews and participants.

Students were first-year undergraduates, most of whom had entered the university directly from preparatory school. All students were required to complete a compulsory two-semester EFL writing course based on their field of study. Further, in university classrooms in the education system of Ethiopia, both English and other subjects are likely to be eclectic in nature.

The Investigation

This study adopted a qualitative case study approach to investigate the relationship between beliefs and actual classroom practices for teaching writing (Borg & Phipps, 2009). Data collection occurred over a period of three months. Sources of data included one scheduled pre-study interview with each of the three teachers, four non-participatory observations of the teachers’ classes with pre-lesson and post-lesson interviews, as well as a collection of random samples of students’ written work. The initial interview questions were piloted with the help of two different teachers not involved in the actual study and the questions were further refined as a result of this process. The interview questions were designed to elicit information about the teachers’ beliefs regarding writing and teaching writing, and about different approaches to teaching writing, including error correction. Other questions were aimed at obtaining information about the teachers’ actual teaching practices as well as factors that influenced their choice of approaches and strategies.

The interviews were the primary research tool used to obtain information about teachers’ beliefs about teaching writing. Based on a structure of four interviews in a series (Seidman, 1998), four interviews of one hour each were scheduled with each teacher: a pre-study interview to establish the context of each teacher’s experience, a pre-lesson interview to obtain information about the lesson to be implemented and a post-lesson interview to help the teachers reflect on the meaning that the whole experience held for them. All the interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed in full and coded.

Four classroom non-participatory observations (McDonough & McDonough, 1997) were carried out over a period of three months with each teacher to obtain information about their actual teaching practices. Specific episodes of events observed during the lessons and the accompanying observer’s field notes were used to generate discussion topics during post lesson interviews. The audio-recordings of the lesson observations were also transcribed, as were the accompanying observer’s field notes. In addition, random samples of students’ marked composition scripts were collected and analyzed for information about the ways teachers approached writing errors. These samples of students’ written work were triangulated (Miles & Huberman, 1994) with data obtained through the interviews and the lesson observations.

Data Analysis

Data collection and analysis involved a cyclical process, and the analysis of the data already collected aided in the successive stages of data collection. Findings from all the varied sources were validated through a triangulation process. For example, data from the individual teacher’s interview, classroom observations and the analysis of students’ composition scripts were matched for convergence and divergence between beliefs and practices. Further analyses of the interview data were focused on the discovery of salient themes and patterns using inductive analysis procedures (Bogdan & Biklen, 1992).

In relating the teachers’ stated beliefs to observational data, my intent was not to simply confirm or disconfirm stated beliefs in the volunteers’ teaching practice. I had expected that there would be occasions when a stated belief was contradicted by practice, perhaps due to constraints. I did not expect a teacher’s practice to either always or never match his or her stated beliefs. Rather, this study’s aim was to examine the extent to which the teachers’ stated beliefs were reflected in their practices.

FINDINGS

To address the three research questions, I discuss the findings of the current study for each of the questions in turn in the sections that follow.

Teachers’ Stated Beliefs

During the interviews, the teachers generally revealed their beliefs about teaching writing. All of them stated that many of their beliefs had been built up over their formal training and many years of teaching writing in varying contexts. They believed that the act of writing involved some kind of process and that it takes time and effort to produce.

T1: Writing is an intellectual activity which takes a lot of time for thinking and analyzing.

T2: Writing is a process through which….

T3: Writing involves thinking, creativity and practice…

Although the teachers said that they took a process approach to teaching writing, they also made their own interpretations about how to apply this approach to writing: “I want my students to understand the processes involved in writing a good composition, as opposed to focusing only on the final product in writing” (T1). He said that this involved getting the students “to understand the different stages a composition goes through from brainstorming to planning, drafting, and peer-conferencing/peer-editing to an eventual final draft composition.” “Teaching of writing,” he added, “also incorporates teaching structural features of the language including controlled practice of writing correct grammatical clauses and sentences.” Thus, his beliefs about teaching writing were consistent with deeper, general beliefs about learning and teaching writing as a process.

The three teachers also made many statements that described their existing writing instruction beliefs and practices. One expressed that the act of “writing takes a lot of time for students to think and analyze and also writing can be a means for students to discover new ideas during the writing process. Make students write more than one draft” (T3). He also said he makes writing activities collaborative: “…drafts are exchanged so that students become the readers of each other’s work.” He also said that feedback on students’ writing “should not focus on grammar alone, but also on the contents of writing.” T2 also shared a similar observation: “Help students [to help] one another shape their writing”. He maintained that writing is a communicative as well as a social act: “One does not write for oneself or only for the teacher but to share with others” (T2). He continued, “It is important to show students how the text conforms or does not conform to the reader’s expectations.”

Tensions between Teachers’ Beliefs and Classroom Practices

The analysis of teachers’ beliefs and practices in teaching writing indicated that generally these were aligned. All three teachers tended to adopt a ‘process-approach’ to writing (Ferris & Hedgcock, 2005), namely, planning, drafting, revising and editing, and writing a final text. However, these data also highlighted a number of tensions between the teachers’ stated beliefs and practices, mainly related to core steps of the writing process. I considered tensions related to three core steps of teaching writing–pre-writing, writing, and revision–by drawing on data from all three participants in the study to illustrate these tensions and the reasons for them.

a) Pre-writing activities

The first example of a tension relates to one teacher’s approach to presenting a writing task. His observed approach was to provide a formal explanation of the issues related to the core steps that the writing process involved, and then to administer a model text to mimic or analyze, followed by possible writing topics for students’ writing. For example, in the first observed lesson, he wrote the topic “Essay writing” on the blackboard and discussed the important tips for writing an effective essay. Then he provided copies of a printed essay, one each for two students, and told them to analyze the important elements that the model essay contained. Students read and tried to highlight the features of the genre. He alleviated their concerns and worked together with the students by identifying the important elements in the essay. Then he assigned each student to write an essay of 500 words for the next class by selecting among the list of titles or topics he had provided them on the blackboard. When he talked about this practice in the post-lesson discussion, though, he explained that it was not something he was satisfied with:

“I didn’t exploit the writing instruction as much as I believe and used to. Today, unfortunately, it is more traditional-teaching. I know it. This encouraged the students to mimic my model. Sorry, I couldn’t help it, you see, [they have to] learn it because there is going to be final exam after a few days… (T1: Post-observation interview 1)”

A key reason for the difference in the ‘before’ and ‘now’ he contrasts here was the time constraint. Previously, he had used varied classroom activities to promote the development of an idea as well as language use, before asking students to write an essay. In this situation, he rushed because he felt he would run out of class time and would not be able to develop the necessary course content before the exam. This approach did not, however, reflect his belief about effective writing instruction, a tension he himself was aware of:

“I know the ideal scenario would be providing students with a source of information to read so that they will use it while writing. Or students could be discussing it. I should have remained in the background during this phase, only providing language support if required, so as not to inhibit students in the production of ideas. But it doesn’t always work like that here. (T1: Post-lesson interview)”

In this example, the tension in the teachers’ work was between ideal and actual ways of teaching writing. He approached essay writing through such a traditional approach not because he felt this was ideal. Rather, he noted that it was due to the contextual factor of constraint in class time that he did not have the students work longer. The teacher also considered that students may lack engagement and motivation if he had used his ideal ways of teaching. He reflected, “Yes, today, for example, I did identify the features in the model essay together with the students. Everybody paid attention then. You see it was more motivating.” (T1: Interview 2).

Thus, his particular belief in the need to motivate and engage students outweighed his general belief in leaving more room for students’ autonomous learning in writing activities: discussing, producing ideas and analyzing by themselves with little intervention or support from their teacher. Although he believed in the value of student-centered writing, he also believed (more strongly it seems) that students learn more when they are engaged cognitively, when their expectations are met, and when they are well motivated.

b) Writing activities

Further evidence of tensions comes from the second and third teachers’ use of controlled grammar activities in class despite doubting their value for acquiring writing skill. During the classroom observation, both the second and third teachers were teaching about ‘revising or avoiding erroneous sentences’. Their teaching approach tended to planned focus-on-form and they were using grammatical terminologies like sentence fragments, comma splice, dangling modifiers, faulty parallelism, etc. Many of their activities and classroom exercises were controlled corrections of grammatical errors. Despite using these regularly, T2 explained that “I don’t like such exercises, I’m trying to move away from them, I don’t think they’re at all beneficial (T2: Post-observation interview). In reflecting on this tension during an interview, the teacher seemed to become aware that he could have used revision tasks better to engage collaboration in pairs or group work with the students rather than individual grammar revision practices.

“I think…erroneous sentences within written discourse…actually that would be interesting…I never noticed that about my teaching…but the problem is the students are still… That that’s why I was doing it…because maybe the students enjoy and expect to do shorter mechanical exercises, rather than longer texts. They may also be aware that such exercises are features of the tests students have to take. “

This is a clear example of how explicit discussion of teachers’ stated beliefs and actual practices can stimulate an awareness of a tension in their work and a deeper understanding of their own teaching. This teacher realized that while he did not believe in the value of learning to write only with the controlled, individual practice of language structures, he did it because he felt that students do expect it. It is also clear from the teacher’s remark that he was “teaching the test” rather than “teaching the subject”. The teacher revealed that his consideration of that feature of the standardized test (language structures) led his teaching approach away from teaching the subject matter in ways he believed were more effective. However, at this University, he argued, students have learned that semester tests for common courses given across various departments are not written by the same teacher who gives the course. Rather, standardized tests are prepared at the department level.

I found a similar tension in the third teacher’s work. This tension was evident after the first observed lesson in which he used a controlled individual work/exercise from a reference book to practice revision of erroneous sentences. This was, he felt, “a very mechanical exercise.” He also believed that he had used it “because it was presented in the text book”–the most available reference book for students in the university’s library.

These two examples show how contextual factors such as students’ expectations, the teachers’ concerns about poor performance, and the teaching material most available to students can cause tensions between teachers’ beliefs and practices. The examples indicated once again how engaging teachers in talking and thinking about these tensions can raise their awareness of them.

c) Error analysis

Analysis of beliefs and classroom practices of the third teacher stood out as uniquely focused on error correction:

“Every time there is an error, I pick it up. I do error analysis almost every day in the class. I believe that effective composing should begin from constructing correct and grammatical clauses and sentences. (T3: Pre-observation interview)”

In the pre-observation conversation, this teacher expressed that he believed written errors should be treated in a way which provokes students’ self-reaction and/or encourages peer correction.

“I believe it would be better eliciting students’ errors through peer correction…to give room for each other to react to their errors. (T3: pre-observation interview) “

During his first class observation, however, I found that this reflection about his particular belief (the need for students’ error correction and feedback) was not congruent with and seemed not to influence his actual practice. He had come back to the classroom with corrected student papers. The papers were students’ written paragraphs, which the teacher had taken with him for home correction. After returning a corrected paper to each student, he chose erroneous sentences from the students’ writing and wrote them on a whiteboard. Then he pointed out each error as he discussed it with the class: errors of verb tense, punctuation, sentence structure, diction, meaning and spelling.

In the post-lesson discussion, his explanation for not using peer correction with pair/group work with teacher’s correction and presentation of error types to correct students’ written errors, was that peer corrections might be time consuming, make it difficult to measure students’ learning and give feedback on errors. He also worried that pair/group work might cause classroom management problems:

“Having them working in pairs or groups, asking each other, would be difficult…How would I monitor them? How would I measure them that everybody is aware of his/her errors? …If they produce something incorrectly it could become fossilized…So I choose to correct them and present. (T3: Post-observation 1)”

Our discussion helped raise his awareness of the tension between his beliefs and his actual practice. In subsequent lessons he consciously decided to try peer evaluation and feedback. He soon found that it actually gave him time in the lesson to monitor students’ learning and to think and adjust the students’ practice as he wished. This gave him more flexibility in teaching writing. It made him feel more, rather than less confident in editing students’ errors, as he had feared might be the case.

DISCUSSION

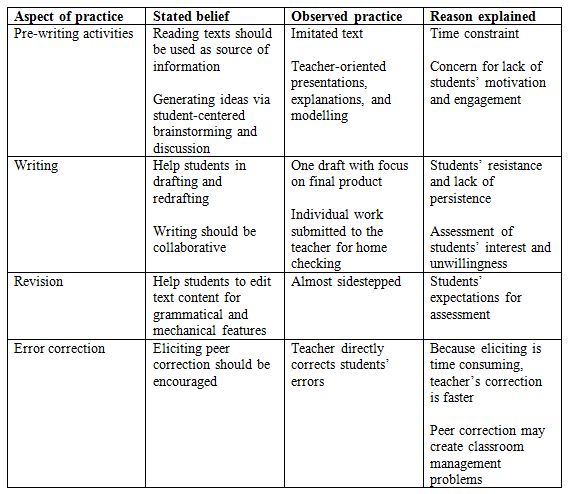

This study suggests that the beliefs of the three teachers studied were not always aligned with their practices. Table 2 is a composite summary of the aspects of writing instruction examined. The beliefs teachers expressed in relation to these aspects of practice, their observed practice in each case, and the factors teachers referred to when accounting for differences between their beliefs and practices are presented. There were several cases where teachers’ professed beliefs about language learning were in strong contrast with practices observed in their lessons. Similar phenomena have been widely reported elsewhere (e.g. Farrell & Kun, 2008; Karavas-Doukas, 1996; Richards et al. 2001).

Table 2. Tensions in writing instruction and beliefs.

In this study, factors which led teachers to teach in ways contrary to their stated beliefs were primarily time constraints, their perceptions of students’ expectations, classroom management issues, and perceived lack of student motivation. Evidence of such factors and their influence on teachers’ work has been noted in previous research (e.g., Andrews, 2003; Li & Walsh, 2011; Burns & Knox, 2005; Mak, 2011). These authors have documented similar findings across contexts in their research studies. I interpreted these findings to mean that features of these contexts are shared with this new Ethiopian EFL context and with previously conducted studies in L1 and/or ESL settings. I argue that one reason for this similarity is shared features of English language teaching in classrooms, irrespective of differences in the setting and national context of English language usage. Although the role of English language teaching and learning varies according to the different national contexts in which it is used (Kachru & Nelson, 2001; Zacharias, 2003), it is commonly held that ELT classrooms are often subjected to various contextual factors beyond the teachers’ beliefs, and that these factors influence teachers’ instructional choices.

The definition of tension cited earlier is nonspecific, and it covers any kind of divergence between what teachers believe and do. The above table, however, illustrates more specifically the different forms in which tensions can occur. Thus, the teachers’ view might be symbolized with the following expressions (with A and B signifying divergent positions): “I believe in A but my students expect me to do B”; “I believe in A but my students seem to learn better via B”; “I believe in A but the curriculum requires me to do B”; and “I believe in A but my learners are motivated by B”.

The tensions found in this study allow for more specific descriptions. However, they are two-dimensional: Some are tensions that the teachers were aware of and had specific reasons for in their teaching practices. As the observer, I brought other tensions to the teachers’ attention. I drew on emerging elements during interviews with the teachers and used these in making classroom observations. Thus T1, in the pre-writing steps, for example, felt that there was tension between his actual and ideal ways of teaching writing, and that this was due to contextual forces such as time constraints that did not allow students to work longer.

This teacher also considered that his students may lack engagement and motivation for his ideal ways of teaching. In the writing steps, however, T2, for instance, seemed to become aware after the post-observation interview with the observer, that there was a tension between his belief on “collaborative/peer revision” strategies and controlled, individual revision practices. This finding was analyzed from this teacher’s response: “…I never noticed that about my teaching.” Another kind of tension which emerges here then takes the form ‘I believe in A but I also believe in B’, with practice being influenced to a greater extent by whichever of these beliefs is more strongly held.

Though the discussion so far has focused on divergences between the beliefs and practices of the teachers in this study, the above analysis also indicated that while teachers’ practices often did not reflect their stated beliefs about language learning, these beliefs were consistent with deeper, more general beliefs about learning. This study clearly evidenced that teachers’ practices reflected their beliefs that learning is enhanced when learners are engaged cognitively, when their expectations are met, when they are well motivated, and when order, control, and flow of the lessons were maintained. These beliefs clearly exerted a more powerful influence on the teachers’ work in teaching writing than their beliefs about the limited value of leaving more room for students’ autonomous learning in writing activities, student-centered writing, and peer correction of errors.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study have clear implications for teacher education. I argued that it is not enough for language teacher cognition research to identify differences or tensions between teachers’ beliefs and practices. Rather, studies should also seek to explore, acknowledge and understand the underlying reasons behind such tensions.

Early studies focusing on tensions between thinking and doing in language teaching suggested that tensions provided a potentially powerful and positive source of teacher training (Freeman, 2002), while more recent work found that a “recognition of contradictions in teaching context” is a “driving force” in teachers’ professional development (Golombek & Johnson, 2004, pp. 323-324). I support such claims and suggest that teacher education programmes would do well to consider ways in which participants can be encouraged to explore their beliefs and their current practices, and the links between them. Collaborative exploration, among teacher educators and teachers, of any tensions which emerge is also desirable. Teacher learning that ensues from such dialogic exploration of teachers’ practices and beliefs has, I believe, the potential to be more meaningful and long-lasting. This study sheds some light on the feasibility of such explorations.

The findings of this study disclosed that “teaching the test” rather than “teaching the subject matter” is one source of tension between what teachers believe and do in classrooms. Borg and Al-Busaidi (2012) claimed this as a well-known problem for language teachers. This has a suitable implication for language teachers in general and teachers teaching writing in particular. I suggest that a teacher can develop tests in other ways than those he/she believes that students expect.

The most salient conclusion drawn from this study was the presence of tensions between what teachers believe and do in writing classes in Wolaita Sodo University. Because Wolaita is largely a macrocosm of university conditions in Ethiopia, this conclusion is likely to apply to writing classes at other Ethiopian universities. As this research revealed, writing classrooms are not an ideal place where every teacher can be expected to consistently employ practices that directly reflect his/her beliefs.

The interviews used in this study valid and reliable through pilot-testing the questions. Participants were volunteers and interested in engaging in the interviews and in being observed while teaching in their classrooms. Data were collected and analyzed objectively and carefully. This methodological approach suggests that studies which employ qualitative strategies to explore language teachers’ actual practices and beliefs may be more productive than, for example, questionnaires about what teachers do and believe, and in advancing our understanding of complex relationships between these phenomena, because participants have an opportunity to explain their responses.

Yet there are still some limitations. First, the interviews were conducted in one institution, Wolaita Sodo University, and the number of participants was far from enough for a systematic study of the problem. If the investigation were carried out in universities in Ethiopia with more qualified professors who had greater experience in teaching writing, and with more participants, perhaps the study results would be more persuasive. Second, owing to the controversial definition of “teacher beliefs”, the interviews, as well as the classroom observations, may have other issues that I failed to address. These limitations were also where I found recommendations for further studies. Firstly, the study can be replicated in another setting. Secondly, if possible, a larger sample could be identified in order to further explore and analyze the phenomena.

References

Aguirre, J., & Speer, N. M. (2000). Examining the relationship between beliefs and goals in teacher practice. Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 18(3), 327-356.

Andrews, S. (2003). Just like instant noodles: L2 teachers and their beliefs about grammar pedagogy. Teachers and teaching, 9(4), 351-375.

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (1982). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Borg, S. (2001). Self-perception and practice in teaching grammar. ELT Journal, 55(1), 21-29.

Borg, S. (2003). Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language teaching, 38, 81-109.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher Cognition and Language Education. Continuum: London.

Borg, S., & Al-Busaidi, S. (2012). Learner autonomy: English language teachers’ beliefs and practices. London: The British Council. Retrieved 23 May 2012, from http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/publications

Borg. S. & Phipps, S. (2007). Exploring relationship between teachers’ beliefs and their classroom practice. The teacher trainer, 21(3), 17-19.

Borg, S. & Phipps, S. (2009). Exploring tensions between teachers’ grammar teaching beliefs and practices. Second Language Writing Journal, 37(4), 380- 390.

Burns, A. & Knox, J. (2005). Relation(s): Systemic functional linguistic and the language classroom. In: Bartels, N. (Ed.), Applied Linguistics and Language Teacher Education. New York: Springer, pp. 235-259.

Ernest, P. (1989). The impact of beliefs on the teaching of mathematics. In P. Emest (Ed.), Mathematics teaching: The state of the art (pp. 249-254). London: Falmer Press.

Farrell, T. S. C., & Kun, S. T. K. (2008). Language policy, language teachers’ beliefs, and classroom practices. Applied Linguistics, 29(3), 381-403.

Ferris, D. R. & Hedgcock, J. S. (2005). Teaching ESL Composition: Purpose, Process, and Practice. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associations, Publishers.

Freeman, D. (2002). The hidden side of the work: Teacher knowledge and learning to teach. Language teaching, 35, 1-13.

Gebel, A., & Schrier, L.L. (2002). Spanish language teachers’ beliefs and practices about reading in second language. In J. H. Sullivan (Ed.), Literacy and the second language learner (Research in second language learning) (pp. 85-109). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Golombek, P. R., & Johnson, K. E., (2004). Narrative inquiry as a meditational space. Examining emotional and cognitive dissonance in second language teachers’ development. Teachers and teaching: Theory and practice, 10(3), 309-327.

Kachru, B. B. and C.L Nelson (2001) World Englishes, in A. Burns and C. Coffin, (Eds), Analysing English in a Global Context. London: Routledge, pp. 9-25.

Karavas-Doukas, E. (1996). Using attitude scales to investigate teachers’ attitudes to the communicative approach. ELT Journal, 50, 187-198.

Kuzborska, I. (2011). Links between teachers’ beliefs and practices and research on reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 23(1), 102-128.

Kynigos, C., & Argyris, M. (2004). Teacher beliefs and practices formed during an innovation with computer-based exploratory mathematics in the classroom. Teachers and Teaching, 10(3), 247-273.

Lefebvre, S., Deaudelin, D., & Loiselle, J. (2006, November). ICT implementation stages of primary school teachers: The practices and conceptions of teaching and learning. Paper presented at the Australian Association for Research in Education National Conference, Adelaide, Australia.

Li, L., & Walsh, S. (2011). ‘Seeing is believing’: Looking at EFL teachers’ beliefs through classroom interaction. Classroom Discourse, 2(1), 39-57.

Lacorte, M. & Canabal, E. (2005). Teacher beliefs and practices in advanced Spanish classrooms. Heritage Language Journal 3(1), 85-107.

Mak, S. H. (2011). Tensions between conflicting beliefs of an EFL teacher in teaching practice. RELC Journal, 42(1), 53-67.

Mansour, N. (2009). Science Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices: Issues, Implications and Research Agenda. International Journal of Environmental & Science Education. 4(1), 25-48

McDonough, J., & McDonough, S. (1997). What’s the use of research? ELT Journal, 44(2), 102–109.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Ng, J. & Farrel, T.S.C. (2003). Do teachers’ beliefs of grammar teaching match their classroom practice? A Singapore case study. In: Deterding, D., Brown, A., Low, E. (Eds.), English in Singapore: Research on Grammar. McGraw Hill, Singapore, pp. 128-137.

Pajares, F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Clearing up a messy construct. Review of educational research, 62(2), 307-332.

Phipps, S. (2010). Language teacher education, beliefs and classroom practices. Saarbrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Richards, J. et al. (2001). Exploring teachers’ beliefs and the processes of change. PAC Journal, 1(1), 41-58.

Savasci-Acikalin, F. (2009). Teacher beliefs and practice in science education. Asia-Pacific Forum on Science Learning and Teaching, 10(1 Article 12), 1-14.

Standen, R. P. (2002). The interplay between teachers’ beliefs and practices in a multi-age primary school. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia.

Tayjasanant, C., & Barnard, R. (2010). Language teachers’ beliefs and practices regarding the appropriateness of communicative methodology: A case study from Thailand. Journal of Asia TEFL, 7(2), 279-311.

Thompson, A. G. (1992). Teachers‟ beliefs and conceptions: A synthesis of research. In D. A. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 127-146). New York: Macmillan.

Zakarias, T. N. (2003). A survey of tertiary teachers’ beliefs about English Language Teaching in Indonesia with regard to the role of English as a global language. Institute for English Language Education Assumption University of Thailand (Unpublished MA Thesis)

Zembylas, M. (2005). Beyond teacher cognition and teacher beliefs: The value of the ethnography of emotions in teaching. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 18(4), 465-487.

This academic article was accepted for publication after a double-blind peer review involving three independent members of the Reviewer Board of the International HETL Review, and two subsequent revision cycles. Receiving Associate Editor: Dr. Marcia Mentkowski, Alverno College, U.S.A., member of the International HETL Review Editorial Board.

Suggested Citation:

Melketo, T. A. (2012). Exploring tensions between English teachers’ beliefs and practices in teaching writing The International HETL Review. Volume 2, Article 11, https://www.hetl.org/academic-articles/exploring-tensions-between-english-teachers-beliefs-and-practices-in-teaching-writing

Copyright © [2012] Tagesse Abo Melketo

The author(s) assert their right to be named as the sole author(s) of this article and the right to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third-party rights including copyright. The author(s) retain their intellectual property rights related to the article. The author(s) assign to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive license to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The author(s) also grant a non-exclusive license to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the author(s).

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution.