HETL Note:

In this academic article, Drs Catherine Snyder, John DeJoy, and Jane Oppenlander discuss the process by which graduate students learn and develop into more self-regulating and mature students and professionals. The authors use transformative learning theory and adult learning theory to support their research. The paper also discusses a theory of graduate education.

Author Bios:

Catherine Snyder is the chair of the Department of Education at Clarkson University’s Capital Region Campus (USA). Snyder has her bachelor’s in economics and Chinese from Smith College, an MBA and Master of Arts in Teaching from Union College, and a doctorate in Curriculum and Instruction from the State University of New York at Albany. She is also a National Board Certified Teacher. Snyder researches transformative nature of graduate education and inquiry teaching strategies. She is a co-author of a book on inquiry methods and has presented nationally and internationally. Snyder spearheads the Summer Institute for Early Career Teaching. This transformative program prepares newly accepted PhD candidates with five weeks of intensive pedagogy coursework in preparation for their undergraduate teaching positions. Her most important job is oversight of the Clarkson Master of Arts in Teaching program where graduates become agents of positive change in schools across the United States. Email: [email protected]

Catherine Snyder is the chair of the Department of Education at Clarkson University’s Capital Region Campus (USA). Snyder has her bachelor’s in economics and Chinese from Smith College, an MBA and Master of Arts in Teaching from Union College, and a doctorate in Curriculum and Instruction from the State University of New York at Albany. She is also a National Board Certified Teacher. Snyder researches transformative nature of graduate education and inquiry teaching strategies. She is a co-author of a book on inquiry methods and has presented nationally and internationally. Snyder spearheads the Summer Institute for Early Career Teaching. This transformative program prepares newly accepted PhD candidates with five weeks of intensive pedagogy coursework in preparation for their undergraduate teaching positions. Her most important job is oversight of the Clarkson Master of Arts in Teaching program where graduates become agents of positive change in schools across the United States. Email: [email protected]

John DeJoy is an Associate Professor in the Reh School of Business at Clarkson University (USA). He has taught college and graduate students for 25 years, preceded by 5 years as an auditor with a Big Four accounting firm. He taught his first fully online course in 1994–using dial-up modems. DeJoy holds the Ph.D. in Adult Education and a master’s in education from the University of Idaho. He holds the MBA and a bachelor’s degree in accounting as well as state licensure as a CPA. DeJoy has published in the areas of pedagogy, corporate social and financial performance, and audit quality. He travels internationally presenting pedagogy workshops to hundreds of professors and PhD students. The workshops have impacted the accounting profession and thousands of students by helping their professors to improve their teaching skills. John coaches select faculty as well. Email: [email protected]

John DeJoy is an Associate Professor in the Reh School of Business at Clarkson University (USA). He has taught college and graduate students for 25 years, preceded by 5 years as an auditor with a Big Four accounting firm. He taught his first fully online course in 1994–using dial-up modems. DeJoy holds the Ph.D. in Adult Education and a master’s in education from the University of Idaho. He holds the MBA and a bachelor’s degree in accounting as well as state licensure as a CPA. DeJoy has published in the areas of pedagogy, corporate social and financial performance, and audit quality. He travels internationally presenting pedagogy workshops to hundreds of professors and PhD students. The workshops have impacted the accounting profession and thousands of students by helping their professors to improve their teaching skills. John coaches select faculty as well. Email: [email protected]

Jane Oppenlander is an assistant professor at Clarkson University (USA) where she teaches statistics for the Reh School of Business and the Clarkson University – Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Bioethics Program. She has over 35 years of experience applying statistics and operations research in the energy industry and is a certified six sigma master black belt. Jane has consulted and published in the fields of transportation engineering, health care, and educational assessment. Her current research interests include statistics education, adult learning, and statistical applications in health care. Jane co-authored a business statistics textbook and a recent casebook on data analysis in health care. She received her Ph.D. in Administrative and Engineering Systems from Union College and an M.S. in statistics, a B.A. in mathematics, and a B.S. in education, all from the University of Vermont. Email: [email protected]

Jane Oppenlander is an assistant professor at Clarkson University (USA) where she teaches statistics for the Reh School of Business and the Clarkson University – Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Bioethics Program. She has over 35 years of experience applying statistics and operations research in the energy industry and is a certified six sigma master black belt. Jane has consulted and published in the fields of transportation engineering, health care, and educational assessment. Her current research interests include statistics education, adult learning, and statistical applications in health care. Jane co-authored a business statistics textbook and a recent casebook on data analysis in health care. She received her Ph.D. in Administrative and Engineering Systems from Union College and an M.S. in statistics, a B.A. in mathematics, and a B.S. in education, all from the University of Vermont. Email: [email protected]

Mapping the Transformative Journey of Graduate Students

Catherine Snyder, John DeJoy and Jane Oppenlander

Clarkson University, USA

Abstract

Researchers map a process through which graduate students in professional degree programs learn and mature. This paper documents evidence of a pattern of transformation among adults participating in graduate programs. The identified pattern simultaneously supports a version of transformative learning theory and has the potential to inform higher education faculty and policy makers regarding potential supports for adult learners.

Keywords: graduate education, transformative learning, andragogy, teacher education, accounting, management, bioethics

Importance of the Problem

The research team embarked on this study to better understand the pattern of development they observed in their professional graduate students. Noticing the shift in identity among the students from the point at which they made the decision to join a professional graduate program to graduation, the researchers asked if a better understanding of this process could improve the quality of their curricular and student service decisions. A pattern of transformation among adults participating in four different graduate programs, including one online, is analyzed and explored. A summary of previous research as well as an explication of this study follows.

Background

The findings discussed in this research study are the progeny of research that was started in 2008 with the initial goal of mapping the transformative (Mezirow, 2000) journey of adults participating in a single teacher education program. That research study indicated that the teacher education program was a transformative experience for the participants and the programmatic claims of transformation were accurate (Oliviera, Snyder & Paska, 2013, Snyder, 2008). That is, both the learning and the education were transformative.

In 2010, a 41-question Likert scale survey instrument was developed using Mezirow’s ten phases in Transformative Learning Theory (TLT) as a guide, and relied heavily on the qualitative data from the initial study. Later, the survey was simplified to ten questions. It was hypothesized that survey data collected from this research would support the findings that graduate programs facilitate transformation in most graduate candidates. The results, however, were inconclusive. In particular, there appeared to be a dissonance between the student self-report data and the pattern of transformation suggested by TLT.

Problem Purpose

The findings discussed in this article are the results from the ten question survey, and attempts by the research team to describe and analyze the dissonance in the self-report data. Additional graduate programs were invited to participate to increase the participant pool and strengthen the validity of the results. With a more precise instrument and larger participant pool, a clear trend emerged that warrants reporting. This finding revolves around the notion that transformation is an iterative process with beginnings and endings that may or may not conform to conventional timelines. What follows is a detailed analysis and interpretation of the aggregate data along with an outline for further research.

Literature Review

This study’s theoretical framework, research questions, and methodology are bounded by a rich body of research. However, little research has been conducted specifically applying TLT in a quantitative manner to master’s level education (Glisczinski, 2007; Oliveira, Snyder, & Paska, 2013; Taylor, 2003). Studies applying the theory using qualitative methods are abundant (Berger, 2004; Snyder, C, 2008, Ziegler, Paulus, & Woodside, 2006) as well as studies analyzing, applying and mapping the theory to undergraduate adult learner experience (Brown, 2005; Cranton, P. 1994, 1996; Featherston, & Kelly, 2007; King, 2002, 2009; Kitchenham, 2006; Mandell, & Herman, 2007; Stansberry & Kymes, 2007; Taylor, 1997, 2007; Tisdell, 1995).

Perhaps the most extensive work in this area was done by Kathleen King. King describes the process of transformation as a “journey” or “pathway” that is followed to greater and lesser degrees of precision by students. With some, the framework put forth by Mezirow is experienced sequentially; with others a more circuitous route moves them from an initial disorienting moment to eventual integration of new ideas and ways of knowing. King developed a Learning Activities Survey (2009) that seeks to better understand emerging prospective transformations and the ways in which curricula might have facilitated those changes. The survey in this study was developed along similar lines with a slightly different goal: to measure the difference in what students self-report as their transformative journey and compare that to the actual theory. The difference, or dissonance, between the two may have the potential to guide faculty and program facilitators regarding ways to better accommodate adult learning. The measure of dissonance has not been explored in TLT literature to date. Secondarily, this research has the potential to recalibrate and enrich the concept of transformation in learning. This secondary goal will be considered at the conclusion of this article.

Theoretical Framework

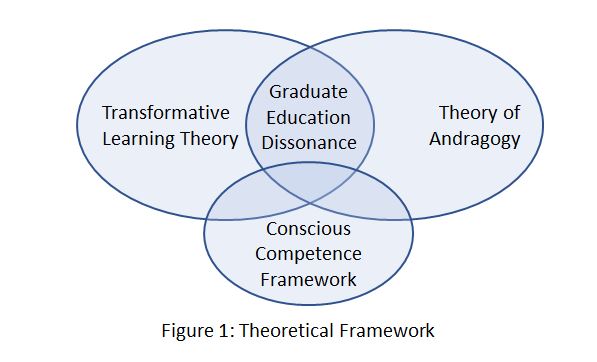

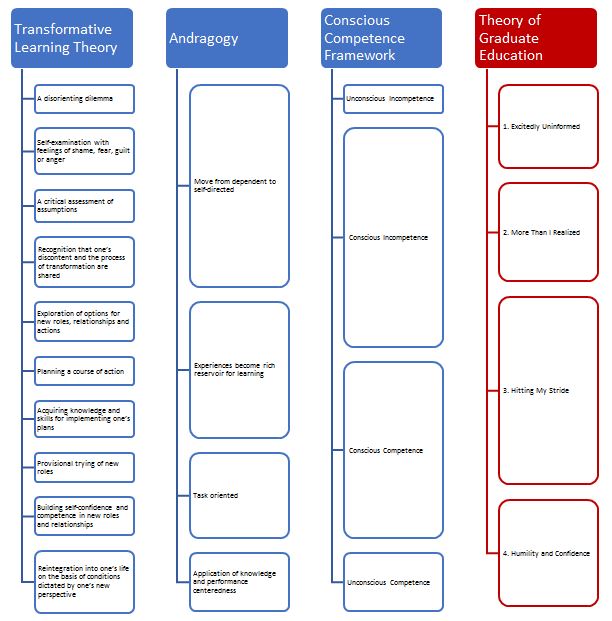

Two primary theories and one framework of adult learning are integrated in this study. (Figure 1). At the outset of the study, Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory (2000) was relied upon as a lens through which to analyze the data. As the analysis proceeded, however, it became clear that a broader understanding of how adults learn was necessary. To that end, we added the Knowles theory of andragogy (1960) and the Conscious Competence Framework (Gullander, 1974) to the theoretical framework. Combined, these two theories and framework assist in the interpretation of the research question and results of the study.

Transformative Learning Theory

The decision to enter graduate school is monumental for most, perfunctory for some. Regardless of the path an individual takes to get to graduate school, the initial demands and challenges are quite often a shock. Surprisingly, most adult learners do not recognize that study of a specific field (as is the case with graduate study) will alter the way they think and the way they view the world. Adult learners entering graduate school experience a shift in their “meaning perspective” (Mezirow, 2000, p. 16) that allows them to incorporate the learning and experiences they encounter into their preexisting “frames of reference” (Mezirow, 2000, p. 7). This process is facilitated by a completely new way of making sense of both self and setting that is more complex than previous frames of reference. TLT is particularly suited to this research because of its specific focus on adult learners.

TLT recognizes frames of reference that are continually being enriched, modified and validated as adults move through life experiences. Frames of reference that are validated over many and varied experiences become reliable. These meaning perspectives are the values and guidelines adults use in their decision making. Transformation changes not what one knows, but how one knows. As Mezirow (2000) writes,

Transformative learning refers to the process by which we transform our taken-for-granted frames of reference (meaning perspectives, habits of mind, mindsets) to make them more inclusive, discriminating, open, emotionally capable of change, and reflective so that they may generate beliefs and opinions that will prove more true or justified to guide action. (pp. 7–8).

Mezirow (1978, 2000) compiled a set of ten phases describing a predictable trajectory that adults move along when challenged in a new way.

- A disorienting dilemma

- Self-examination with feelings of shame, fear, guilt or anger

- A critical assessment of assumptions

- Recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared

- Exploration of options for new roles, relationships and actions

- Planning a course of action

- Acquiring knowledge and skills for implementing one’s plans

- Provisional trying of new roles

- Building self-confidence and competence in new roles and relationships

- Reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by one’s new perspective. (2000, p. 22)

While the phases themselves are not meant to be linear or comprehensive, the theory provides a lens through which analysis of adult learning experiences is possible.

Andragogy

Malcolm Knowles is commonly referred to as the father of modern andragogy and was one of the first theorists to recognize the impact of the idea that adults learn differently than children or adolescents. Knowles differentiated the study of adult learners from the larger field of pedagogy with four assumptions:

These assumptions are that as individuals mature: 1) their self-concept moves from one of being a dependent personality toward being a self-directed human being; 2) they accumulate a growing reservoir of experience that becomes an increasingly rich resource for learning; 3) their readiness to learn becomes oriented increasingly to the developmental tasks of their social roles; and 4) their time perspective changes from one of postponed application of knowledge to immediacy of application, and accordingly, their orientation toward learning shifts from one of subject-centeredness to one of performance-centeredness. (Knowles, 1960)

Knowles’ assumptions align with TLT in several ways. First, both theorists recognize that as adults accumulate experience, that experience is taken into account in future decision making. Second, learning is very task-oriented and dependent on social roles. As is the case with the graduate students in this study, they are all seeking a particular new role (accountant, teacher, manager, and bioethicist) which is quite specifically tied to skills and social interactions. They move from a sense of disorientation at the beginning of their graduate study, to a phase of planning and acquisition of new skills, to an integration of learning into previously existing frames of reference in order to adapt to the demands of their new social and professional roles.

Conscious Competence Framework

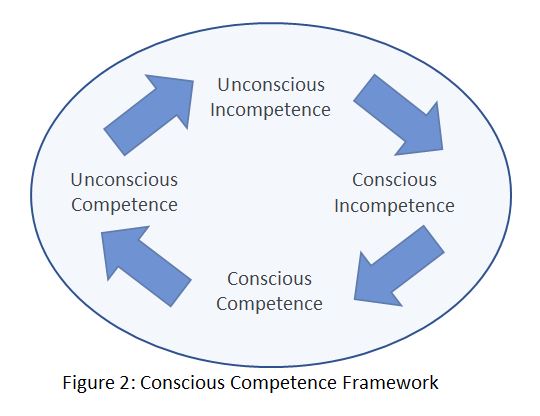

The Conscious Competence Framework origins are unclear. It first appeared in literature in the 1970s, primarily in organizational theory and industrial training literature. The earliest known reference to the framework was in an article written by Gullander in 1974 in which he interviews W. Lewis Robinson, then vice president of industrial training for International Correspondence Schools. In the article, Robinson outlines the theory as a natural movement from not knowing what we don’t know, to being aware of deficits, and moving toward mastery of those deficits. In the mastery of deficits, adults move from a phase during which they are aware of their competency (conscious competence) toward a phase in which they are unaware of their competency (unconscious competence). Robinson cautioned that unconscious competence has the potential to be problematic because individuals who are unconsciously competent tend to stagnate in their work, not recognizing the need for further development. Unconsciously competent individuals also make poor mentors as they are no longer able to deconstruct their expertise. (See Figure 2.)

For the purposes of this study, the first three phases are particularly relevant. Most students enter graduate school unconsciously incompetent or perhaps consciously incompetent. This orientation resonates with Mezirow’s first phase of TLT which indicates that adults often experience disorienting dilemmas when encountering a new learning demand. As one moves from unconsciously incompetent to consciously incompetent, a sense of unsettledness occurs. The degree of unsettledness, or disorientation, will depend on the individual and his or her background and temperament.

When TLT is combined with an andragogy and the Conscious Competence Framework, an integrated framework emerges that allows for a rich interpretation of our data. Aligned next to each other, there is a logical progression from dependence and uncertainty to self-directed learning and confidence.

Methodology

This study reports the results of a survey administered to graduate students to ascertain the extent to which self-reporting shows evidence of the transformative process. A questionnaire was developed based on initial qualitative analysis and quantitative analysis (Snyder, 2008). This study addresses the following research questions:

- Can the TLT phases be discerned from student self-reporting?

- How do students’ perceptions of their graduate work change over the course of a graduate program?

Invitations to participate in this research, including a link to the questionnaire, were emailed to all enrolled graduate students at selected departments of two institutions of higher education. One institution is graduate-only; students in the management, bioethics, and education schools were asked to participate. Students from the other institution were enrolled in the graduate program in bioethics.

The survey was refined based on feedback from several pilot groups and validated by independent researchers familiar with TLT. The institution review boards of both institutions reviewed and approved this study and associated data collection tools.

Findings

A total of 219 surveys were returned from a population of 562 students resulting in an overall response rate of 39%. The response rates for each of the questions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Survey results

| TLT Phase | Question | Response Frequency | Disagreement

|

Neutral

|

Agreement | ||||

| 1 | I feel overwhelmed by my pursuit of a graduate degree. | 216 | 98.6% | 85 | 39.3% | 73 | 33.8% | 58 | 26.9% |

| 2 | When I examine my decision to pursue a graduate degree, I am fearful about the direction of my life and career. | 214 | 97.7% | 117 | 54.7% | 44 | 20.5% | 53 | 24.8% |

| 3 | I critically examined assumptions I had about my graduate degree. | 212 | 96.8% | 19 | 9.0% | 50 | 23.6% | 143 | 67.4% |

| 4 | I realize other students share feelings of uneasiness about our graduate degree. | 164 | 74.9% | 38 | 23.2% | 25 | 15.2% | 101 | 61.6% |

| 5 | I recognize I have to take on new roles and responsibilities in pursuing my graduate degree. | 210 | 95.9% | 7 | 3.3% | 22 | 10.5% | 181 | 86.2% |

| 6 | I am making plans for my post-graduate career. | 212 | 96.8% | 14 | 6.6% | 28 | 13.2% | 170 | 80.2% |

| 7 | I am acquiring new knowledge and skills to become effective in my post-graduate career. | 211 | 96.3% | 5 | 2.4% | 11 | 5.2% | 195 | 92.4% |

| 8 | I am experimenting with roles and responsibilities that will be expected of me in my post-graduate career. | 209 | 95.4% | 15 | 7.2% | 41 | 19.6% | 153 | 73.2% |

| 9 | I am building skills now that I will need in my post-graduate career. | 208 | 93.5% | 7 | 3.4% | 17 | 8.2% | 184 | 88.4% |

| 10 | Even though I have not yet completed my graduate degree, I feel like a professional in my post-graduate career. | 209 | 95.0% | 21 | 10.1% | 45 | 21.5% | 143 | 68.4% |

The demographic characteristics of the respondents are summarized in Table 2. Approximately 10% chose not to provide demographic information.

Table 2.

Respondent demographic characteristics

| Career Status | Response Frequency | |

| Advancing current career | 104 | 47.5% |

| Career changer | 44 | 20.1% |

| No prior work experience | 56 | 25.6% |

| No response | 15 | 6.8% |

| Work Experience (years) | ||

| 0-5 | 114 | 52.0% |

| 6-10 | 31 | 14.2% |

| >10 | 58 | 26.5% |

| No response | 16 | 7.3% |

| Median (Range) | 4 (0-48) | |

| Degree Being Pursued | ||

| Certificate | 8 | 3.7% |

| Masters | 178 | 81.3% |

| Doctoral | 8 | 3.7% |

| Other

(Undergraduate, Medical, Non-matriculating) |

10 | 4.5% |

| No response | 15 | 6.8% |

| Graduate School Discipline | ||

| Bioethics/Medicine | 65 | 29.7% |

| Business | 97 | 44.3% |

| Education | 31 | 14.2% |

| Engineering Management | 11 | 5.0% |

| No response | 15 | 6.8% |

| Stage in Program (% of courses completed) | ||

| Beginning (0-33) | 46 | 21.0% |

| Middle (34-67) | 58 | 26.5% |

| End (> 67) | 78 | 35.6% |

| No response | 37 | 16.9% |

| Age | ||

| 20-29 | 115 | 52.5% |

| 30-39 | 31 | 14.2% |

| 40-49 | 21 | 9.6% |

| ≥ 50 | 36 | 16.4% |

| No response | 16 | 7.3% |

| Median (Range) | 26 (20-71) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 112 | 51.1% |

| Male | 88 | 40.2% |

| No response | 19 | 8.7% |

Overall, participants report varying levels of agreement with TLT in Phases 3-10. For Phases 3-10, a majority of respondents (61.6% – 92.4%) reported experiencing the transformational steps. Phase 9 (building skills) responses show that a strong majority of participants (89%) report that they are building their skills. This strong affirmative response is the second-highest level of agreement across the ten phases and might be expected of students enrolled in professionally-oriented master’s degrees. Only 8% answered with the neutral response and a mere 3% disagreed. The responses to the culmination of Mezirow’s theory, Phase 10 (feel professional), indicate that 65% of the students report they have integrated their learning and feel like they are professionals in their field.

For Phases 1 (overwhelmed) and 2 (fearful), the modal response was disagreement (39.3% and 54.7%, respectively). The Phase 2 question received the highest level of disagreement among all ten questions. Fully 59% of students report that they are not fearful which seems contrary to TLT’s assertions regarding Phase 2.

The survey participants represent a broad demographic range as seen in Table 2. The survey results have been analyzed using specific demographic factors to better discern transformational patterns.

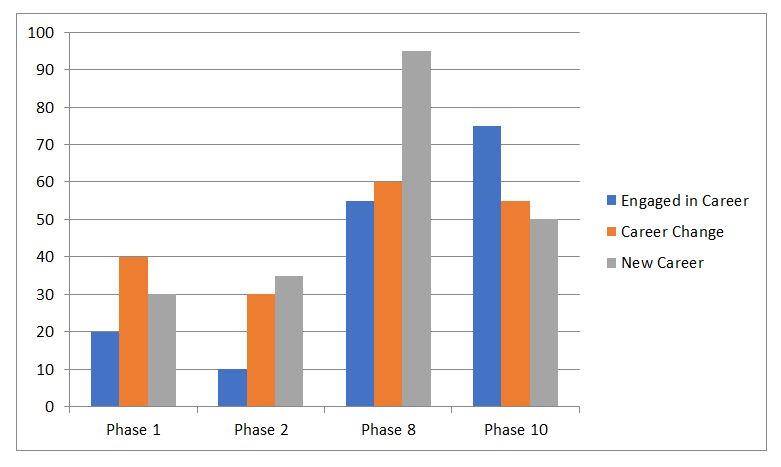

Analysis by Career Status

The survey provided three career status response options: advancing current career, career changer, and no prior work experience. In Phases 1 and 2, a χ2 test shows statistically significant differences in agreement by career status with career changers and those with little work experience showing higher rates of agreement than those already in a profession (Phase 1: p = 0.0142 and Phase 2: p = 0.008). The 8th TLT phase, role experimentation showed a significantly higher level of agreement for those with little work experience compared to career changers and those already engaged in a career (p = 0.0212). Finally, those already engaged in a career were more likely to feel like a professional (Phase 10) than career changers or those with little prior work experience (p= 0.0084).

Figure 3. Highlights these observations by showing only Phases 1, 2, 8, 10 below.

Analysis of Student Transformation by Stage (Beginning, Middle, End)

The “beginning” stage of the graduate program is defined as having completed no more than one-third of the coursework. Similarly, the “middle” and “end” stages are defined as having completed no more than two-thirds and completing more than two-thirds of coursework, respectively. A χ2 test was conducted for each TLT phase question to determine if there are differences based on stage of graduate program completion. For all 10 questions, there were no statistically significant differences in the ratings based on stage of graduate program completion.

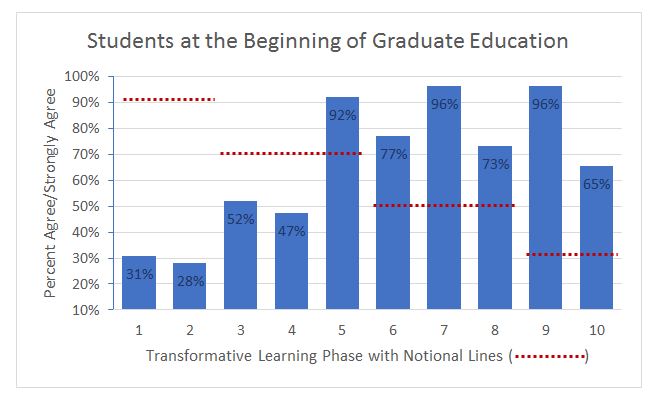

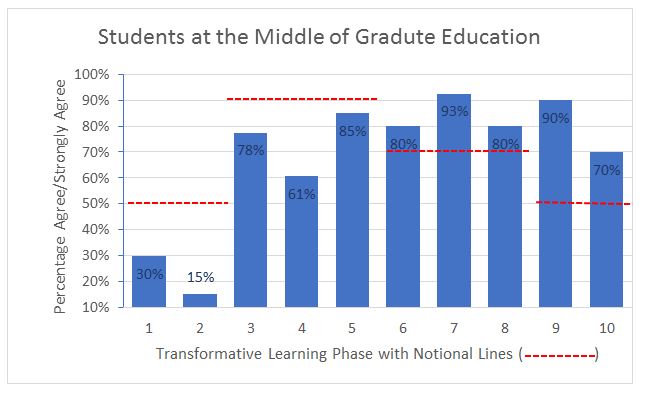

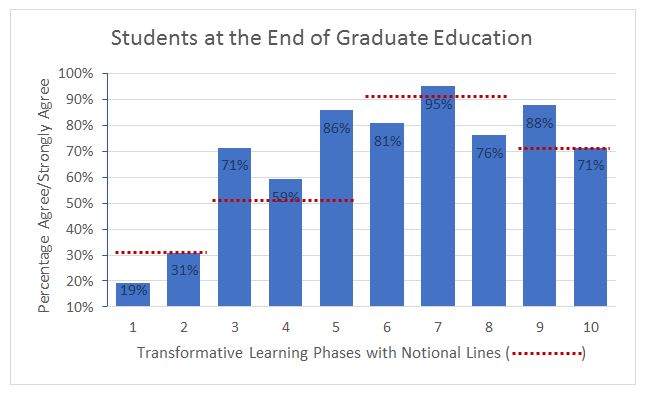

Figures 4-6 depict the survey results divided across students in the three stages. One might expect to see a strong sense of agreement with the first few phases of TLT among beginners and a gradual move toward strong agreement with later phases as students approach graduation. While this is the general trend, some unusual patterns emerged from the data which are discussed below.

Along with the actual data for beginning, middle and end students are horizontal lines labeled ‘notional lines.’ These notional lines represent the approximate location at which we researchers anticipated students to be in each phase. For example, we anticipated that many more beginning students would have agreed with the statement reflecting Phase 1 (overwhelmed). The notional line for that phase is placed at 90% on the graph representing our estimate of how many students would agree or strongly agree. However, only 38% of beginning students agreed or strongly agreed. Our estimates and the notional lines are based on the qualitative research completed prior to this survey study (Oliviera, Snyder & Paska, 2013; Snyder, 2008) as well as the work of others who have analyzed the transformational trends of graduate students (Berger, 2004; Ziegler, Paulus, & Woodside, 2006).

The notional lines also group together Phases 1 and 2, 3 through 5 (assumptions, shared feelings, and new roles), and 6 through 9 (making plans, acquiring new knowledge, role experimenting, building skills, and feeling professional). This grouping is based on the work of Kathleen King. King describes the qualitative and quantitative work she has done using TLT (2009):

The transitions from instrumental and/or communicative to emancipatory learning and from received knower to constructed knower are embedded in [the transformative learning] model…Rather than an isolated learning moment, the journey emphasizes that there is a direction that some take – a general path which leads to perspective transformation – as they engage in adult learner-grounded professional development…(p. 92)

Nohl (2015) also groups Mezirow’s phases into more encompassing steps. Nohl’s research pointed toward five phases: a non-determinant phase, an experimental and undirected inquiry phase, a social testing and mirroring phase, a shifting relevance phase, and finally a social consolidation and reinterpretation of biography phase. Like King and Nohl, we agree that people on a transformative journey will follow a trend toward perspective transformation that gradually allows them to reach the final phases in TLT, “building competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships” and “a reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by one’s new perspective” (Mezirow, 2000, p. 22). At the same time, while evidence in the data has emerged to indicate that TLT may be an appropriate starting point for an analysis of graduate level learners, an adaptation of the original theory may be in order. Thus, you might say that the notional lines represent our best assessment of where students should be at a particular stage in their graduate education. These lines do not, in all cases, align with the data. This dissonance will be addressed in the final section of this article.

The question then becomes, what is prompting the dissonance between hypothesized outcomes and the actual results? Take the example provided above: where 38% of beginning graduate students agreed or strongly agreed that they are experiencing disorientation. The framework put forth by Robinson in the Gullander article might help to explain the dissonance between the predicted outcome and the actual. Robinson explains that there is an introductory period during which new learners are unaware of the depth of their ignorance on a topic. During this time period, their behaviors might be characterized by overconfidence in the new skills and knowledge being acquired (Gullander, 1974). Similarly, the graduate students in this study might be demonstrating that ignorance.

A second confounding element may also be at work. Faria (1987) in his work with business students, observed that life changing decisions often precede the decision to enter graduate school. So it is also possible that many of the graduate students moved through the first phases of TLT prior to enrolling in their respective graduate programs. If so, it would help to explain the difference between prediction and the outcomes.

Figure 4. Students at beginning of graduate education.

Finally, researchers believe that even though the results of this survey were anonymous, it might be difficult for many graduate students to admit that they are feeling apprehensive. After all, most students make significant life changes and financial commitments in order to pursue a graduate degree. Admitting that there is some sense of anxiety associated with the decision might be too much for one’s ego to bear.

Another trend in the results produced by beginning students is how quickly they appear to be moving toward transformation. Their profile is closer to what one would expect of a middle or end of program student. The only indication that they might be new to the program is the slight drop in agreement with Phases 6 and 8. These phases deal with planning and acquiring knowledge in the new field of expertise. Since students at the beginning of a program will not have gained large amounts of new information, it makes sense that there is a relative drop in agreement in those two phases.

It could be that students simply do not know what they do not know yet (unconscious incompetence). All of the graduate programs studied include an internship or expect students to be working in a field related to their studies. Students at the beginning of an internship might feel confident that they are acquiring knowledge and building competence in new roles (Phases 7 and 9 – acquiring new knowledge and building skills) despite the fact that they may only be a couple of weeks into a new professional environment.

The dissonance between what was expected and the actual results for the middle and end of program students was considerably less compared to students at the beginning of the program. Indeed students at the middle and end of the program seem to align with TLT. In many phases, students in the middle of the program come closest to meeting the notional lines predicted by the researchers. This could indicate that students in the midst of graduate school might be completing one transformational journey (their shift toward a new professional identity) and beginning a new transformational journey as a teacher, bioethicist, manager or accountant.

The results from one phase of TLT were striking across all three groups. Phase 4 (shared feelings) points to a “recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared.” (Mezirow, 2000, p. 22). In Figures 4-6, the level of agreement with this statement was low across all three sets of students. It is also important to note that this question had the lowest response rate in the survey. Only 71% of participants chose to answer this question, while all other questions were answered by over 90% of the participants (see Table 1). Since the theories supporting this study consider shared experience an integral aspect of transformation, this result warrants some analysis. The participant population may not have understood the survey question clearly (“I realize other students share feelings of uneasiness about our graduate degree”). It is also possible that the embedded assumption – that one is feeling uneasy about pursuing a graduate degree – is false. This conclusion is supported by the results for questions reflecting Phases 1-3. Finally, it is possible that many graduate students simply do not have the opportunity or inclination to share feelings, particularly doubt or anxiety, with classmates. The traditionally competitive environment present in many graduate programs would deter most students from expressing these emotions.

Figure 5. Students at middle of graduate education.

Figure 6. Students at end of graduate education.

Toward a Unifying Theory of Graduate Education

The research points toward a dissonance between what adult learning theory postulates and self-report data of graduate students. This in turn points toward an opportunity to fine tune our theoretical understanding of the way graduate students learn in order to more effectively provide improved pedagogy and interventions to foster student success. More theoretical work needs to be done to synthesize adult learning theories into a transformative learning-oriented model for graduate education. However, an initial framing is provided in the column “Theory of Graduate Education” of Figure 7. Students typically enter their professional graduate education program excitedly uninformed. Typically, they have done considerable research on the profession and program; yet, the demands of the work required to gain membership into that profession still elude them. In phase 2, more than I realized, students begin to recognize the depth of the commitment they have made – both financially and intellectually – and experience doubt, questioning and reappraisal. In phase 3, hitting my stride, students who are able to move past phase 2 find they gradually build the social and intellectual capacities to succeed in the professional program. And finally, phase 4, humility and confidence. In this phase students are both confident about their skills and ability to enter their profession, but humbled by the knowledge that being a professional is much more than obtaining a degree. Students in this phase will readily show appreciation for more able classmates, faculty, and mentors as they move into their chosen professional settings.

This rendition of transformative learning applied to graduate education is in its early research stages. Enough data have been analyzed and compared to existing theories to recognize that those existing theories fall short of explaining the professional graduate experience. However, more work must be done to establish this new iteration of transformative learning theory.

Figure 7. Unifying theory of graduate education.

Directions for Future Research

We believe the mapping of the transformative learning process is a rich vein of research that should be fully explored. We envision that this research will explore the commonalities and differences between the various disciplines that may lead to a set of best practices both across disciplines and by discipline. Ultimately, graduate faculty should be introduced to transformational learning theories with the goal of adjusting the instructional milieu to best enhance graduate student success.

References

Berger, J. G. (2004). Dancing on the threshold of meaning: Recognizing and understanding the growing edge. Journal of Transformative Education, 2(4), 336-351.

Brown, K. M. (2005). Transformative adult learning strategies: Assessing the impact on pre-service administrators’ beliefs. Educational Considerations, 32, 18 – 26.

Cranton, P. (1994). Understanding and promoting transformative learning: A guide for Educators of adults. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cranton, P. (1996). Professional development as transformative learning: New perspectives for teachers of adults. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Featherston, B. & Kelly, R. (2007). Conflict resolution and transformative pedagogy: A grounded theory research project on learning in higher education. Journal of Transformative Education, 5(3), 262-285.

Faria, A. J. (1987). A survey of the use of business games in academia and business. Simulation & Gaming, 18(2), 207-224.

Glisczinski, D. J. (2007). Transformative higher education: A meaningful degree of understanding. Journal of Transformative Education, 5(4), 317-328.

Gullander, O. E. (1974). Conscious Competency: The Mark of a Competent Instructor. Canadian Training Methods, 7(1), 20-21.

King, K. P. (2002). Identifying success in online teacher education and professional development. Internet and Higher Education, 5(3), 231-246.

King, K. P. (2009). Handbook of the evolving research of transformative learning. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Kitchenham, A. (2006). Teachers and technology: A transformative journey. Journal of Transformative Education, 2, 202 – 225.

Knowles, M. (1960). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Cambridge Book Co.

Mandell, A., & Herman, L. (2007). The study and transformation of experience. Journal of Transformative Education, 5(4), 339-353.

Mezirow, J. (1978). Education for perspective transformation: Women’s reentry programs in community colleges. New York Center for Adult Education, Teachers College, Colombia University.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Nohl, A. (2015) Typical Phases of Transformative Learning: A Practice-Based Model. Adult Education Quarterly, 65(1), 35-49.

Oliveira, A., Snyder, C., & Paska, L. (2013). STEM career changers’ transformation into science teachers. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 24(4), 617-644. doi:10.1007/s10972-012-9325-9

Snyder, C. (2008). Grabbing hold of a moving target: Identifying and measuring the transformative learning process. Journal of Transformative Education, 6(3), 159 – 181.

Stansberry, S. L., & Kymes, A. D. (2007). Transformative learning through “Teaching With Technology” electronic portfolios. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 50 (6), 488 – 496.

Taylor, E. W. (1997). Building upon the theoretical debate: A critical review of the empirical studies of Mezirow’s transformative learning theory. Adult Education Quarterly, 48, 1, 34 – 60.

Taylor, E. W. (2003). Attending graduate school in adult education and the impact on teaching beliefs: A longitudinal study. Journal of Transformative Education, 1, 349 – 366.

Tisdell, E. J. (1995). Creating inclusive adult learning environments: Insights from multicultural education and feminist pedagogy. (Information Series No. 361). Columbus, Ohio: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education.

Ziegler, M. F, Paulus, T. M, & Woodside, M. (2006). “This course is helping us all arrive at new viewpoints, isn’t it?” Making meaning through dialogue in a blended environment. Journal of Transformative Education, 4(4), 302-319.

This feature article was accepted for publication in the International HETL Review (IHR) after a double-blind peer review involving independent members of the IHR Board of Reviewers and two revision cycles. Accepting editor: Dr Charlynn Miller

Suggested citation:

Snyder, C., DeJoy, J., & Oppenlander, J. (2017). Mapping the Transformative Journey of Graduate Students. International HETL Review, Volume 7, Article 6, https://www.hetl.org/mapping-the-transformative-journey-of-graduate-students

Copyright 2017 Catherine Snyder, John DeJoy and Jane Oppenlander

The author(s) assert their right to be named as the sole author(s) of this article and to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third party’s rights including copyright. The author(s) assign to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive licence to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The author(s) also grant a non-exclusive licence to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the author(s).

Disclaimer:

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution. By publishing this article, the author(s) affirms that any original research involving human participants conducted by the author(s) and described in the article was carried out in accordance with all relevant and appropriate ethical guidelines, policies and regulations concerning human research subjects and that where applicable a formal ethical approval was obtained.