HETL Note:

In this academic article, John Delacruz discusses how educators can foster creativity in students by developing effective communication skills through entertaining and engaging storytelling across different media channels.

Author Bio:

John Delacruz is responsible for the advertising program’s creative track and developing links between industry and education. He also develops collaborative projects for students nationally and internationally. Primarily concerned with experiential learning spaces and their impact on the creative disciplines, John is championing the use of technology as a way to enhance and add value to the student experience. He also teaches User Experience Design at Miami Ad school in San Francisco. Innovative and creative forms of engagement inspire John’s classes. Creative and strategic thinking, ideas generation and pushing the boundaries of traditional communications form the backbone of his curricula where students solve real world problems in ways that enhance their employability in an ever competitive advertising world. Integrated solutions, advertising for good, user experience and engagement are key areas of interest that drive the tasks he sets his students.

John Delacruz is responsible for the advertising program’s creative track and developing links between industry and education. He also develops collaborative projects for students nationally and internationally. Primarily concerned with experiential learning spaces and their impact on the creative disciplines, John is championing the use of technology as a way to enhance and add value to the student experience. He also teaches User Experience Design at Miami Ad school in San Francisco. Innovative and creative forms of engagement inspire John’s classes. Creative and strategic thinking, ideas generation and pushing the boundaries of traditional communications form the backbone of his curricula where students solve real world problems in ways that enhance their employability in an ever competitive advertising world. Integrated solutions, advertising for good, user experience and engagement are key areas of interest that drive the tasks he sets his students.

Socially Minded: Ethical Awareness and the Creative Advertising Student

John Delacruz

San Jose State University, USA

Abstract

Creativity can be a powerful driver for brand communications. Entertaining and engaging, we tell the world stories across media channels that encourage consumption and allow brands a central role in shaping identities, communities and history. Advertising often comes under fire for encouraging conspicuous consumption and establishing unattainable desires among consumers. Worst, advertising is accused of hoodwinking innocent consumers into spending money they haven’t got on things they don’t need. Yet we persevere, crafting campaigns that are fun to interact with and building brands that resonate emotionally with consumers. As educators in the field of advertising and other creative industries we should be guiding our students to make ethically minded decisions, not just to continue the cycle of consumption of which we, as communicators, are integral spokes.

Students are generally attracted to careers in advertising by the commercials they see on TV, shared on YouTube, by the brands that they engage with and that have become a big part of who they are as consumers. They don’t often follow a path into the ad industry because they want to make the world a better place. Ironically, our students have grown up with social currency, they are a sharing generation, global citizens, media aware and ethically minded. They are already switched on to alternative futures and therefore open to guidance on how to use their creativity for good.

It is our responsibility as educators to actively enable our students to explore ways where the power of creativity can be harnessed for ethically directed communications. This case study will focus on examples from the advertising program at San Jose State University where students actively engage and work on briefs set by non-profits, environmental and community engagement organizations. By engaging with live clients with real problems to solve, students on this program learn by doing, they meet in their studio, an experiential learning suite designed on the lines of an advertising agency. They work in agency and/or creative teams and learn about issues affecting urban neighborhoods (gun violence, teen pregnancy, drug abuse), the environment (inland creeks and rivers, the Pacific coast), and human rights. The program offers them experience reflecting the world of work and the world around them. They hopefully become informed, engaged and aware citizens as well as effective and creative communicators.

Introduction

“Great creativity is astonishingly, absurdly, rationally, irrationally powerful. Great creativity can spread tolerance, champion freedom, make education seem like a bright idea. Great creativity can turn a spotlight on deprivation, or show that deprivation ain’t necessarily so. Great creativity can make politicians electable, or parties unelectable. It can make war seem like tragedy or farce.” (Hobsbawn, 2008)

Creativity is, indeed, a very powerful force. The advertising industry relies on creative expression to help brands appeal to an increasingly cynical and media-savvy consumer base so a big part of the educator’s role is to help channel our students’ creativity in ways that will enhance their career prospects upon graduation. Inevitably we drive students to compete in award shows, create spec campaigns, work on live client briefs and enable them to develop a portfolio that showcases a range of skills and approaches. The way students solve the problem, interpret the brief, will result in a range of solutions and executions in any given class with most feeling their idea is unique or innovative. There may be differences in approach within a class of twenty students as the instructor guides each team in different directions, but when a brief is replicated across schools on an almost global level such as in the case of an award show, the same ideas and executions crop up multiple times. Originality does not define the true worth of advertising necessarily, creatively presenting and crafting an idea for effectiveness, to achieve and exceed intended business goals, is where the value of advertising is measured. Yet effectiveness and creativity go hand in hand (Reinartz & Saffert, 2013) but this is not to be confused with “originality” as is often the case with the student interpretation. Students strive for originality, but creativity in advertising comes from observation, understanding, empathy, and the pulling together of pop culture references, user interests that triggers emotion, and deep knowledge of the brand / problem / user triangle.

Creativity happens when the advertiser creates meaning for the viewer (Lehnert, 2014). Meaningfulness coupled with divergence, is essential to creativity in advertising. Human to human advertising (Kramer, 2014) bridges the gap between brand and consumer and truly engages through relationship building. Interactions of this kind are meaningful to consumers but they do not just happen, insight and understanding emerge from an empathic approach to research – the human centered design approach as championed by IDEO and others, for instance. So, the creative forces at work for brands and products requires deep level understanding and empathy of people as well as business. Creativity is therefore born of knowledge, empathy and understanding, soft skills our students are to grow in preparation for their entry to the creative industries. As educators, we help our students develop these skills through spec briefs, or award shows, or live client briefs. All serve as practical examples, real world scenarios, experiential learning moments. These experiences should not only be commerce-led. If we are teaching soft skills like empathy, should we not be using the teaching moment to encourage our students to become agents of change? To identify and empathize with the environment or with refugees or with victims of crime? When we bring the nonprofit, the cause related problem, into the classroom we are adding another layer to our students’ learning experience. We also enable an ethical dimension to enter the curriculum, one through which our students can understand that creativity can work to improve the world, if only just by a little bit.

For the purposes of this article nonprofits are determined as any organization that is essentially working for the good of the community, the environment, the local or global population and are not commercial concerns.

Award shows include nonprofit and awareness briefs and this is an excellent way to engage students with ethical approaches to advertising communications. Award shows are also global in nature and, although they add value to the learning experience, they do not add a point of difference to the student portfolio. A good way to add value to the learning experience and contribute to a cause is by working with local, grass roots nonprofits. Engaging with organizations like Save Our Shores, for instance, enables students to experience working with a live client, seeing their work go live if successful, engage in community and service learning, develop knowledge of environmental issues and grass roots activism, whilst creating work for their portfolio and the organization. This approach features prominently in the advertising program at San Jose State University. The creative track has developed relationships with a number of local grass roots nonprofits that are mutually beneficial and always result in fresh thinking due to the essential nature of live client work – i.e. the brief is always new and current each semester. The following case studies highlight the work produced for a range of nonprofits under varying circumstances and analyzes the benefits to students, organization and university.

These cases, typical in the ad program at San Jose State, are examples of service learning or experiential learning. Practical learning methodologies address the needs of future employers by allowing our students the space to explore and practice their craft, to solve problems in real world contexts. Employability is an issue in Higher Education and as educators, mentors, guides that help students develop and grow into future practitioners we must ensure our graduating cohorts meet industry needs. In IBM’s white paper: “Pursuit of relevance: How higher education remains viable in a dynamic world” we understand that “the best ways to address performance gaps (in industry) are through experience-based learning” and when we are “offering more practical and applied education experiences, institutions help students apply the knowledge gained through coursework in real-world settings” (King, Marshall & Zaharchuk, 2015). Service learning equips students with the practical skills they need to perform well after graduation and instils a sense of ethics in the work they do.

Case Study #1: Save Our Shores

“Save Our Shores is a 501(c)3 nonprofit marine conservation organization in Santa Cruz, California. Our mission is caring for the marine environment through ocean awareness, advocacy, and citizen action.

Over the last 30 years, Save Our Shores has been responsible for key accomplishments such as preventing offshore oil drilling in Central Coast waters, helping to establish the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, preventing local cruise ship pollution, and bringing together diverse stakeholders to find common solutions to ocean issues. Today we focus on educating youth about our watersheds, tackling plastic pollution on our beaches and rivers, advocating for plastic-free communities, managing Annual Coastal Cleanup Day in Santa Cruz and Monterey counties, running our nationally renowned Dockwalker program, and providing our community with educated and inspired Sanctuary Stewards! Our three core initiatives are Plastic Pollution, Ocean Awareness, and Clean Boating. Whether we’re advocating in the community for local bans on single-use plastic bags and polystyrene containers, or tackling cigarette butt litter with our BaitTanks and No Butts About It campaign, we are busy protecting our most valuable resource here on the Central Coast: the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary.”http://saveourshores.org)

Save Our Shores (SOS) may be a small organization but they are accomplished campaigners, active in the community all around Monterey Bay all year round. They advocate, they campaign around marinas and harbors, and reach out to local schools with educational programs and projects. The relationship between San Jose State’s Advertising Program and SOS began with a brief to promote their annual July 5th Beach Clean-Ups. This project ran over five weeks and was given to students on the Copywriting course. The brief asked for a copy-driven campaign to work in print media and out of home targeting natives of the wider Bay Area, particularly those who travelled to the beaches of Monterey Bay (ie they were predominantly day visitors who did not have a personal stake in the beaches around Santa Cruz). A project of this nature, with a very clear scope, is a perfect introduction to ethical communications and community engagement or service learning.

Community engagement pedagogies, often called “service learning,” are ones that combine learning goals and community service in ways that can enhance both student growth and the common good. In the words of Vanderbilt University’s Janet S. Eyler and Dwight E. Giles, Jr., it is

“a form of experiential education where learning occurs through a cycle of action and reflection as students. . . seek to achieve real objectives for the community and deeper understanding and skills for themselves. In the process, students link personal and social development with academic and cognitive development. . . experience enhances understanding; understanding leads to more effective action.” (Eyler & Giles, Jr., 1999)

Working with SOS as a client allowed the Copywriting students to not only work on solving a communication problem as a classroom activity, they were also able to fulfill important service learning needs as well. Students had, up to this point, worked on exercises that helped them apply classroom learning. These exercises are standard copywriting activities that enable students to practice headline writing, or radio scripting, or writing long-form copy. They then worked on an award show brief before receiving a briefing live by SOS. Being briefed by the communications manager of SOS enhances the learning experience as it is understood to be different to a regular classroom activity. A real-world problem is understood by students to have more value than a spec problem (a spec brief is a fantasy brief usually created by the instructor. Spec is diminutive of speculative) as it is rooted in reality. There is a sense of competition too. The winning team would see their work in print. The value here cuts three ways – students who win have a portfolio project that made it into the real world; the organization have a series of print ads designed for them pro-bono and they also fulfill their outreach goals; the university is actively involved in the community by association thereby fulfilling the outreach and service commitments of their mission. Through a project like this, students are taking control of their own learning – they have been given theories and shown case studies, they have practiced through classroom exercises, now they have to navigate the problem as autonomous teams. To a point of course. “The role of the instructor in the experiential classroom is different than in the traditional classroom. In the experiential classroom, the instructor is a guide, a cheerleader, a resource, and a support.” (Schwartz referencing Warren, 1995, Chapman, McPhee & Proudman, 1995). Students need to work independently, to learn by doing, and the instructor acts as a guide ensuring learning moments are maximized and, to a greater extent, directing the creative process thus effectively acting as creative director to the student teams, again a nod to the overall creative process students will experience in industry.

When students work on a brief like this they must go out into the field and research, develop insights, craft a Big Idea, and develop a creative strategy for communicating this idea. Most of this work happens outside the classroom and it offers students a variety of learning moments that will enhance their professional skill set and their ethical awareness. Although some students were native of coastal areas and already had an appreciation of and relationship with the marine environment, most were not. Most were typical of the target audience – they lived inland and used the beach for recreation during summer days, particularly key dates like 4th July, Labor Day and Memorial Day. Before the project started most students were unaware of the environmental impact that heavy beach use during the summer months was having on the California coast. As part of their research some, not all, participated in beach clean-ups and gained first-hand knowledge of the problem they were trying to solve – how to communicate a Leave No Trace message to an audience who were unaware of how their actions impacted on the wider marine environment. They learnt that personal littering has a cumulative effect that impacts on marine mammals, their habitats and the food chain. They learnt about the respect that volunteers have for the marine environment and they developed a respect themselves. 80% of students who took the brief were affected personally, i.e. by the end of the project they had a deeper understanding of the issues SOS were communicating and had developed a new-found respect and, in some cases, a desire to actively advocate for the cause. The other 20% were already aware of these issues, were regular beachgoers, active ocean users (surfers, etc.) and/or had lived on the coast for a long time.

The work was seen to be successful overall. The winning team had their work in print (Figs. 1 and 2) and they learnt the value of deep understanding – of issue and audience – and

empathy with a cause – in this instance they became deeply involved in marine environmental advocacy.

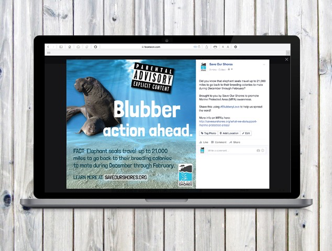

Figures 1, 2 and 3

They made pop culture references in their copy in order to address the audience in a tone of voice both engaging and relatable. Their imagery was not of litter strewn beaches, rather the images were uplifting highlighting the beauty of the beach environment. Their creative skills were developed and their understanding of an environmental issue was woven into the development of their product. They became active service learners and gave back to the community, advocating on behalf of SOS. Their benefit was a body of work in the public space. A portfolio piece as talking point that would help them communicate their real-world skills to future employers. Other notable examples (Figs. 3, 4 and 5) were also successful in their mission. All students in the class benefited from hands-on experiential service learning. They became actively involved in the creating for good and they learnt that creativity is a powerful tool that can be used in pursuit off ethical goals.

This project signaled the beginning of a relationship with Save Our Shores that has enabled students in both the Copywriting and the Art Direction classes to engage with a non-profit on a live brief. The relationship has burgeoned because the work produced by the students has consistently been innovative and of a high standard. The organization has benefited from fresh thinking, interns working on mini campaigns and livelier messaging. Briefs have been topical as with the July 5th campaign above. Both Art Direction and Copywriting have received briefs aimed at developing awareness of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and the most recent, and successful, project asked Copywriters to create a multi-touchpoint campaign encouraging California residents to vote in favor of keeping the plastic bag ban.

One of the MPA briefs focused on digital and social media with students creating campaigns for Instagram and Facebook. The aim of the brief was to inform the target audience of the different MPAs along the Northern California coast highlighting the richness of flora and fauna both in the ocean and on land. This particular assignment resonated with most students and the results were interesting in a number of ways. It is important to note that the brief is launched by the SOS Communications Director.

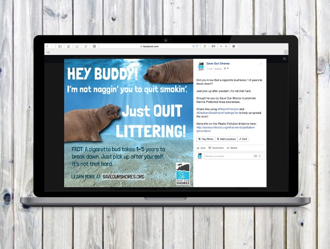

Figures 4 and 5

He sets a context and answers questions in class. At the briefing it became clear that an upbeat tone was required. Too many environmental campaigns suffer from a doom and gloom tone of voice or may attempt to shock by illustrating man made destruction without offering hope. This campaign was to be awe inspiring and celebratory so the target audience would feel encouraged to protect the MPAs when they visited them. 80% of teams approached the brief in this way, 20% resorted to the voice of doom. It may be that students were not taking note of these requirements, or they did not understand that this was a key direction set by the client. It is highly likely that these students resorted to a default way of thinking – environmental advertising is successful when it instils guilt or shocks an audience – and no amount of advice would sway them from this approach. In fact, the teams who resorted to this approach rationalized their ideas throughout the process. The experiential learning approach adopted requires that ultimately students will decide on their direction. Guiding them is important, but they must choose their path after arriving at their own conclusions. This is a big part of the learning process. Their mistakes become evident in the final result and feedback, from both instructor and client, and they then understand the importance of remaining on-brief.

The student teams who did follow the brief to the letter and applied creative thinking within these set parameters fared better as they gave the client work that solved the problem in creative ways and met their requirements. The winning idea (Figs. 6, 7 and 8) gave the campaign a personality that was warm and friendly. The message communicated successfully and the team responsible interned at SOS developing their idea for a live launch in the Fall of 2016.

Not only did these students learn the client/agency process (to a point), they also developed their client relationship skills and were immersed in the pre-launch process of an advertising agency. They became aware of how to meet client needs in real time without sacrificing their creative vision and produced a body of work that will influence real people on a serious issue. Their work will also feature prominently in their portfolios which, together with the real-world experience gained, will positively impact their employability post-graduation.

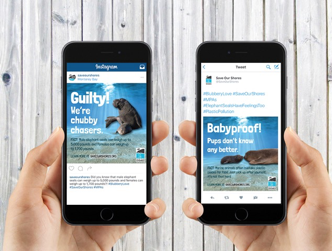

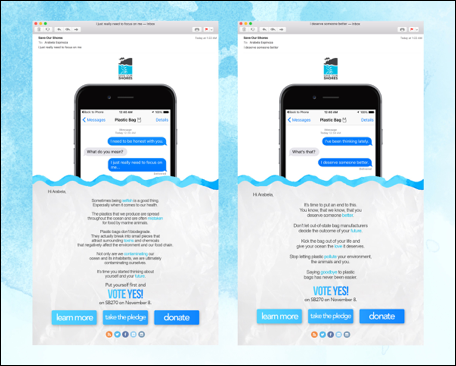

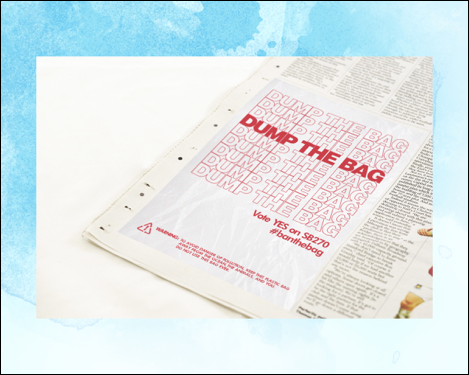

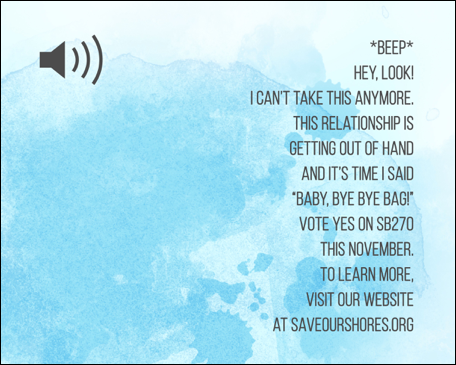

The final project to present in this case study was one where students had to really step outside of their comfort zone in terms of media choices. An email campaign supported by radio and print encouraging California residents to vote in favor of keeping the plastic bag ban proved successful in terms of professional skills development and environmental policy awareness. Media requirements were challenging for every team because students are not used to thinking about email as an advertising channel even though they are subject to email advertising on a daily basis. Thinking about email in non-traditional ways was necessary to shatter preconceptions of this messaging format. Approaches to storytelling underpinned student learning in this assignment. Successful teams approached each email as a chapter in a story building engaging narratives exploiting media format and the way that users read email. Teams that did not approach the email aspects of the campaign in this way resulted in weaker storytelling and disjointed campaigns.

Figures 6, 7 and 8

The most successful campaign was one that looked at the problem, the issues surrounding plastic bag use and pop culture relevant to the target audience. They equated the ban to a relationship break up because of our dependency on plastic bags for convenience and through habit. The winning team created an engaging, fun campaign that enabled them to develop their communication skills in a number of ways.

First of all, they realized that environmental messaging should not be about presenting doomsday scenarios – again 20% of the class resorted to this approach regardless of the information they were given and a generally agreed awareness of how consumers have become desensitized to shock imagery in charity advertising. They had to research state legislation and the legal process, they became aware of an individual’s voting responsibilities, part of their learning necessarily developed their knowledge of plastic bags and the marine environment. These issues had to be understood before they were able to ideate and craft a creative campaign. Knowledge of the target audience, how they respond to emails, when they are likely to hear radio advertising and where they will interact with other social media channels – key aspects of consumer behavior that had to be studied prior to strategizing their creative campaign. Developing a level of understanding in areas that may not be considered core to the practice of advertising are key to its practice. An advertising practitioner needs to develop empathy with the target and must have a deep knowledge of the client’s business. An advertising practitioner wears many hats throughout the execution of their duties and it is the multi-faceted nature of the craft that makes the job rewarding and challenging. Students working on a live brief with a live client get to truly experience, to a degree, the practice they hope to be a part of once they complete their studies.

This particular assignment proved beneficial on a wider basis too. SOS, in partnership with San Jose State and the Museum of Art and History in Santa Cruz, created a showcase event for all the projects. Campaigns were displayed and a judging process that invited community participation

became the central focus of a campaign that had grown beyond the classroom. The live interaction between students in a Copywriting class and an environmental non-profit was now benefiting more stakeholders in numerous ways:

- Students at SJSU engage with a live client, develop awareness of working practices in the advertising industry, develop knowledge of the marine environment and the impact of plastic bags, develop their knowledge of state legislature and the legal process, understand consumer behavior, actively develop their creative practice. They enrich their educational experience.

- Save Our Shores educate a new group of potential environmental stewards and receive a series of creative communications approaches and strategies. They are able to communicate their message more effectively. Through the event their work becomes visible outside of Santa Cruz County.

- San Jose State University are associated with a grass roots marine environmental no-profit via press releases and wider community outreach. The SJSU brand is clearly visible at the Museum of Art and History and across media coverage of the campaign, the event and the partnership.

- The wider Santa Cruz County community become participants in the direction of the Keep The Ban campaign. They actively engage with the issues at the heart of the project, namely the vote to keep the plastic bag ban in place and the negative impact of plastic bags on the marine environment.

It therefore becomes clear that a project of this nature has wide reaching benefits to a number of stakeholders. An experiential learning exercise harnesses environmental stewardship, community outreach and support for the University’s mission. Students also become aware of ethical issues that impact on their habitat. The communications manager for Save Our Shores comments on the relationship between SOS and SJSU as such:

“John’s advertising and copywriting courses offer a unique experience for everyone involved. From Save Our Shores’ perspective, we have an opportunity to interact with a diverse group of talented students, teach them about issues impacting our marine environment, and craft engaging messages together that mobilize our advocacy campaigns.

My favorite part of the partnership is working one-on-one with student groups toward a social good. Each group offers a different perspective on how to promote and educate our constituents on ocean related issues. This creates a lot of value for Save Our Shores. The relationship is truly symbiotic. Partnering with John’s classes at SJSU affords students the opportunity to build their resumes with real world experience, experience that uses creativity for good. Every project we do has the potential to go live and to actually become the face of my organization’s next campaign. From promoting the ecological integrity of Marine Protected Areas to helping build awareness about the California Statewide Bag Ban, student work is not only used, it’s celebrated within the community. The partnerships often end in public recognition, something I hope will inspire student’s in the industry to continue seeking out opportunities that give back. Without John’s foresight to approach nonprofits with such experiences, our community would be missing out on building meaningful connections that have the potential to change the world.”

Below are examples from the winning campaign idea.

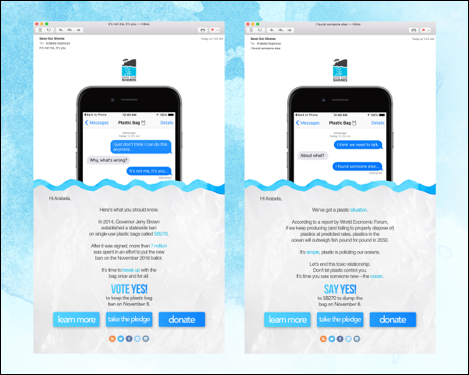

Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14

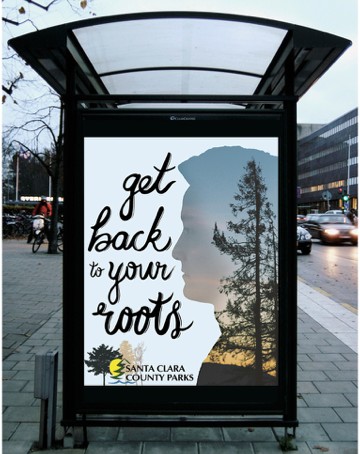

Case Study #2: Love Your Parks and Art in the Park

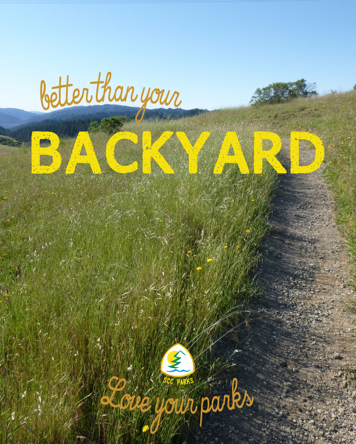

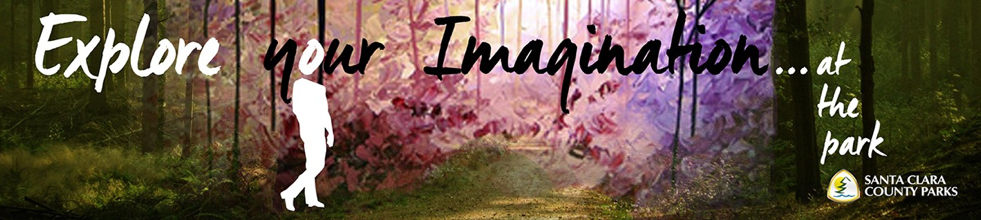

Local grassroots environmental organizations provide excellent opportunities for students in the creative fields because, du to budget constraints, they cannot necessarily hire professional agencies or manage an in-house team of any great size. The opportunities afforded students are reciprocal – students engage with a live client, produce real-world work, compete against each other, develop awareness of ethical issues in practice and the organization engages a new audience who develop professional standard communications for the portfolio experience, the academic assignment, or, at times, an internship opportunity. With the case to be discussed students, and the university, benefited in other ways too. Initially a simple live brief classroom assignment designed to create awareness for a Santa Clara County Parks (SCCP) community event, the project led to a commission by SCCP for an interpretive signage installation in one of the county parks. The signage project grew into a wider reaching art in the park initiative at Hellyer Park in San Jose, California.

Love Your Parks challenged students to engage with the richness of the County’s public parks. An event celebrating these urban and suburban green spaces would enable students to connect with the amenities they would be communicating to an audience of time poor urban dwellers. Two sections of the Art Direction class competed against each other working on, mainly, print based solutions for communicating the event. In order to empathize with the issue and the organization students developed their knowledge of parklands from a number of standpoints. They appreciated the differences between city, county, state and national parks, they became aware of the need for green spaces and outdoor recreation in urban settings. They also became aware of how underused these facilities were.

Understanding the cultural and social priorities demonstrated by the target audience would help them change attitudes. Time poor urban dwellers, many of whom were commuters, found little time or had little interest in exploring the parks in the county. Although young families were the main target, these users rarely used their parks. Anderson, Boud and Cohen claimed that one of the defining characteristics of experiential learning is:

“Recognition and active use of all the learner’s relevant life experiences and learning experiences. Where new learning can be related to personal experiences, the meaning thus derived is likely to be more effectively integrated into the learner’s values and understanding.” (in Foley, 2001)

This became true when students found the best way to connect with their audience was through reflection of their own experiences with parks. Memories and nostalgia became the lens through which most teams solved the problem. Imagery alluding to childhood experiences and family outings, typography that hinted at nostalgic sentiment, copy that took the audience back to their childhoods and encouraged them to want the same for their own children. They asked their audience to explore their imaginations, to go back to their roots (nature) and that the expansive parklands were more substantial than their tiny back yards.

The work was warmly received by the client and although in this instance students were not to benefit from publication or an internship, some submissions were awarded at the Silicon Valley American Advertising Federation’s ADDYs Awards. Students who were awarded at the ADDYs effectively received recognition for their efforts from the regional advertising industry. This benefit is worth more than an internship in some cases as the students are establishing contact with potential employers in an industry that thrives on networking, certainly where creative positions are concerned.

As with the Save Our Shores relationship, a mutually beneficial project evolved that enabled students to understand how advertising communications can impact on lifestyles and the environment. Although SCCP is a governmental body, the work was not for profit. Understanding consumer attitudes and changing these for good rather than profit was valuable in terms of industry insight, community service and environmental awareness. The results of a successful partnership can be long lasting as with SOS. In this instance, a new project was proposed that would see a greater degree of community engagement and creative autonomy take shape. The project that evolved out of Love Your Parks was tentatively titled Art in the Park as it would encompass a growing number of public art installations sited at Hellyer Park in San Jose, California. Initially responding to a need for interpretive signage on a three mile stretch of trail, the project became an opportunity to understand the mentorship aspects of an experiential learning exercise whilst also enabling students to actively engage with the immediate environment and, in particular, the wildlife in Hellyer Park and the Coyote Creek Trail.

Case Study #3: Amnesty

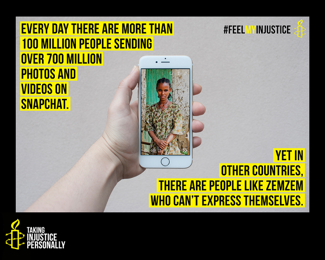

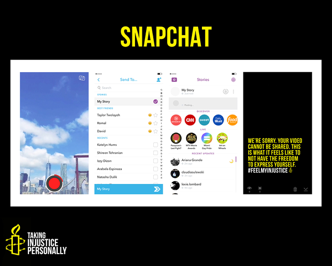

The Amnesty project was one that grew out of an Award Show brief for D&AD. The brief asked students to address an issue Amnesty had noticed among millennials – a lack of empathy with victims of human rights abuses outside of their (the millennial audience in the US and UK) own proximity. In other words, if human rights abuses were happening somewhere else, this audience did not feel it had an impact on them. The challenge was to change perceptions – human rights abuses affect everyone directly or indirectly. The Pew Research Center, in their report on Millennials in Adulthood (2014) noted the unique perspective held by millennials where they were characterized as “more racially and ethnically diverse, less religious and more liberal than older adults”, yet dialogs around oppressed and excluded minorities are often shut down because the concept alienates those in the majority, “creating a notion of blame or feelings of guilt”. Understanding of and empathy with oppression/oppressed minorities are ethical principles that a socially aware advertising curriculum should push. The “challenge is to uncover ways to engage students in dialogues both in and out of the classroom about excluded and oppressed minorities that foster critical thinking rather than blame or feelings of guilt”. High impact learning practices, like experiential learning, are suggested, as are learning communities and community-based learning (Kuh 2008). The following case study does not require students to engage in community based learning but the studio itself became a learning community. Initial research and thoughts, new knowledge and ideas, were all shared in a common space through group critiques and tutorials. The structure of the assignment was rooted within experiential learning practices, in keeping with a studio approach in the teaching of creative subjects.

Figs. 15, 16, 17, 18, and 19

Students who worked on this project developed a number of key skills, mainly empathy and understanding as well as the ability to creatively communicate an idea through a range of media channels. They all focused on a variety of issues that Amnesty campaigns about – from reproductive rights to human trafficking – in order to find commonalities between the audience and oppressed/excluded minorities. Understanding the issues, they selected through research was important as, in this instance, they were the target audience with little or no empathy between those affected by human rights issues and themselves. Their learning curve was evident. As the brief was open ended, students had to grasp the nature of human rights from two angles – human and legislative. They needed to understand the convention of human rights and the laws we are guided by as well as developing an awareness of moral and ethical responsibility. Initial, and very broad, research was shared in discussion groups before teams ideated their own focal point.

As the work developed it became clear that this group of students, representative of the millennial generation and the values and approaches common to them, could become passionate and vocal activists when they became immersed in a subject. Each piece of work demonstrated depth of thought and engagement with issues they had previously been unfamiliar with. Of course, the main learning objective for these students is not same as for a social justice student working on a similar assignment. Creative practice and the ability to convincingly communicate an idea through a range of media channels is the main task they are trying to achieve, but they cannot successfully meet that goal without the in-depth understanding of the issues involved. The benefits to advertising students in this case are, as in the other case studies presented here, evident. They are learning key creative skills through practical, hands-on exercises. They are applying a big idea to a range of connected media channels – from the social space to radio to print. They are also learning about wider world issues and making them relatable. they became informed in human rights issues and were able to understand how they impact on everyone and not just the minority who are directly affected. In this instance, they effectively engaged in dialog about ethical issues that they may otherwise have not had the opportunity to do.

The learning experience here is paramount – students are learning a bad curriculum within the confines of their own discipline. The Amnesty brief, and others like it, allow students to not only engage with real world issues in a real-world scenario, but also to compete with others like them. The best pieces were submitted to a major student showcase by the One Club in New York at their annual Creative Week event. The students involved developed portfolio pieces that were seen on a wider stage as a result. The examples below are typical of the work from this assignment.

This campaign seeks to demonstrate how we take our freedom of speech for granted through social media channels commonly used by millennials. The print executions are self-explanatory, the Snapchat and Instagram examples build on the use of these channels as a way of expressing our views freely. Users attempting to upload a video or an image will be met with a temporary error message demonstrating how their messages are being stifled. This is a simple way to communicate censorship using the native properties of each media channel. The students who focused on reproductive rights, also seen below, used commonly recognized icons that represent our right to choose. the condom wrapper in this instance becomes the message carrier within the advertising space. All the students involved in the project were mainly junior level with another semester or full academic year to go before graduation. This is a key point in their skills development and they will take this awareness of the power of advertising to communicate for good into their final senior year and the capstone course that will define the moment they are ready to progress into the creative workplace. The experience gained through a project like this will help them understand the responsibilities they have as communicators with conscience.

Conclusions

A progressive curriculum for advertising students should combine creativity, strategic thinking, and ethics. An ethically-led teaching strategy enables students in the creative disciplines to locate themselves within a broader global space with an understanding of and empathy with the issues that affect citizens outside of their own immediate experience. It helps to embed awareness of issues that have a direct impact on the world around them and helps them understand how their actions have consequences on others. In other words, embedding ethics within the advertising curriculum helps shape communicators of conscience, ensures our students become responsible communicators who will use their creativity strategically to impact positively on society. They may well continue to further commercial pursuits, but they will also be able to influence consumers, citizens, to act responsibly, to help others, the environment, to vote and think deeply about who they elect to positions of power.

Figs. 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24

An ethical approach does not need to be limited to lectures on ethics and essays on ethical behavior. The discipline of advertising is, by its very nature, hands-on, practical. A practical approach to ethical advertising can benefit the organizations it works with and, in turn, reflects positively on the university or college. An ethical approach need not simply refer to the standard definitions of advertising ethics – are consumers misled, does advertising perpetuate stereotypes, etc – but can be interpreted as a way to encourage students to focus their creativity on helping others, the environment, on doing good. Helping students become responsible citizens and practice their craft at the same time.

The case studies discussed in this article demonstrate how a practical approach to encouraging advertising students to be ethically minded practitioners can meet the need to cover ethics, creativity and strategic thinking in the curriculum. By partnering with grass roots organizations, the students on San Jose State University’s advertising program are beginning develop positive practices that they will hopefully carry into the workplace, helping them drive responsible approaches to advertising communications. By adopting a service learning approach we find that there are three beneficiaries: the student who gains real world experience and an understanding of ethical practices, the organization that receives greater exposure and new advocates, and the university when it is recognized as a partner promoting positive actions. The partnerships are important, a good communications manager willing to collaborate fully in the learning process helps to make the project a success, as Eyler, Giles and Dwight (1999) state: “Researchers have found that … personal and interpersonal gains from engaging in service-learning classes were higher when the programs were of better quality. The biggest predictor of increased learning in communication skills was the high placement quality that the students were put into, allowing them to develop and “hone” their skills.”

References

Andresen, L., Boud, D. and Cohen, R. (2001) Experience-Based Learning: Contemporary Issues, pp 225-239, in Foley, G. (Ed.). Understanding Adult Education and Training. Second Edition. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Eyler, J. and Giles, Jr., D. (1999), Where’s the Learning in Service-Learning? San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Hobsbawm, A., (2008). Do the green thing. TED 2008, Monterey, California. Retrieved from: https://www.ted.com/talks/andy_hobsbawm_says_do_the_green_thing

King, M., Marshall, A., Zaharchuk, D. (2015). Pursuit of relevance: How higher education remains viable in today’s dynamic world. Somers, New York: IBM Corporation.

Kramer, B., (2014). There is no B2B or B2C: It’s Human to Human #H2H. Retrieved from: http://www.bryankramer.com/there-is-no-more-b2b-or-b2c-its-human-to-human-h2h/

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Lehnert, K. (2014). Advertising creativity: The role of divergence versus meaningfulness. Journal of Advertising, 43(3) pp. 274-285.

Millennials in adulthood: Detached from institutions, networked with friends. Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. (March 7, 2014) Retrieved from: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/03/07/millennials-in-adulthood/

Reinartz, W. and Saffert, P., (2013). Creativity in advertising: When it works and when it doesn’t. Harvard Business Review, June 2013.

Schwartz, Michelle. (2013). Best practices in experiential learning. Retrieved from: http://www.ryerson.ca/content/dam/lt/resources/handouts/ExperientialLearningReport.pdf

Illustrations

Figs. 1-5 Save Our Shores “July 5th CleanUp” Campaign, ADV 124 Copywriting, Spring Semester 2014

Figs. 6-8 Save Our Shores “MPA” Awareness Campaign, ADV 124 Copywriting, Fall Semester 2015

Figs. 9-14 Save Our Shores “Dump The Bag” Campaign, ADV 124 Copywriting, Spring Semester 2016

Figs. 15-19 Santa Clara County Parks “Love Your Park” Campaign, ADV 125 Advertising Layout and Production, Spring Semester 2015

Figs. 20-24 Amnesty International “Taking Injustice Personally” Campaign, ADV 124 Copywriting, Spring Semester 2016

This feature article was accepted for publication in the International HETL Review (IHR) after a double-blind peer review involving independent members of the IHR Board of Reviewers and two revision cycles. Accepting editor: Dr Charlynn Miller

Suggested citation:

Delacruz, J. (2017). Socially minded: Ethical awareness and the creative advertising student. International HETL Review, Volume 7, Article 4, https://www.hetl.org/socially-minded-ethical-awareness-and-the-creative-advertising-student

Copyright 2017 John Delacruz

The author(s) assert their right to be named as the sole author(s) of this article and to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third party’s rights including copyright. The author(s) assign to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive licence to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The author(s) also grant a non-exclusive licence to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the author(s).

Disclaimer:

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution. By publishing this article, the author(s) affirms that any original research involving human participants conducted by the author(s) and described in the article was carried out in accordance with all relevant and appropriate ethical guidelines, policies and regulations concerning human research subjects and that where applicable a formal ethical approval was obtained.